On March 22, citing rampant intellectual property theft, President Trump announced $50 billion in penalties on Chinese goods. Then, on April 5, he rolled out another $100 billion in tariffs when China retaliated. This all followed on the heels of his March 1 declaration of a 25 percent tariff on steel imports and a 10 percent tariff on aluminum imports, which would have a small but not altogether insignificant effect on China.

Trump’s moves baffled and enraged mainstream economists. But they also exposed the deep ideological rifts that exist on trade and China in the United States. In particular, they represent a dilemma for the labor movement and the left—and a chance to chart a new path forward, one focused less on inter-state competition and more on shared struggle.

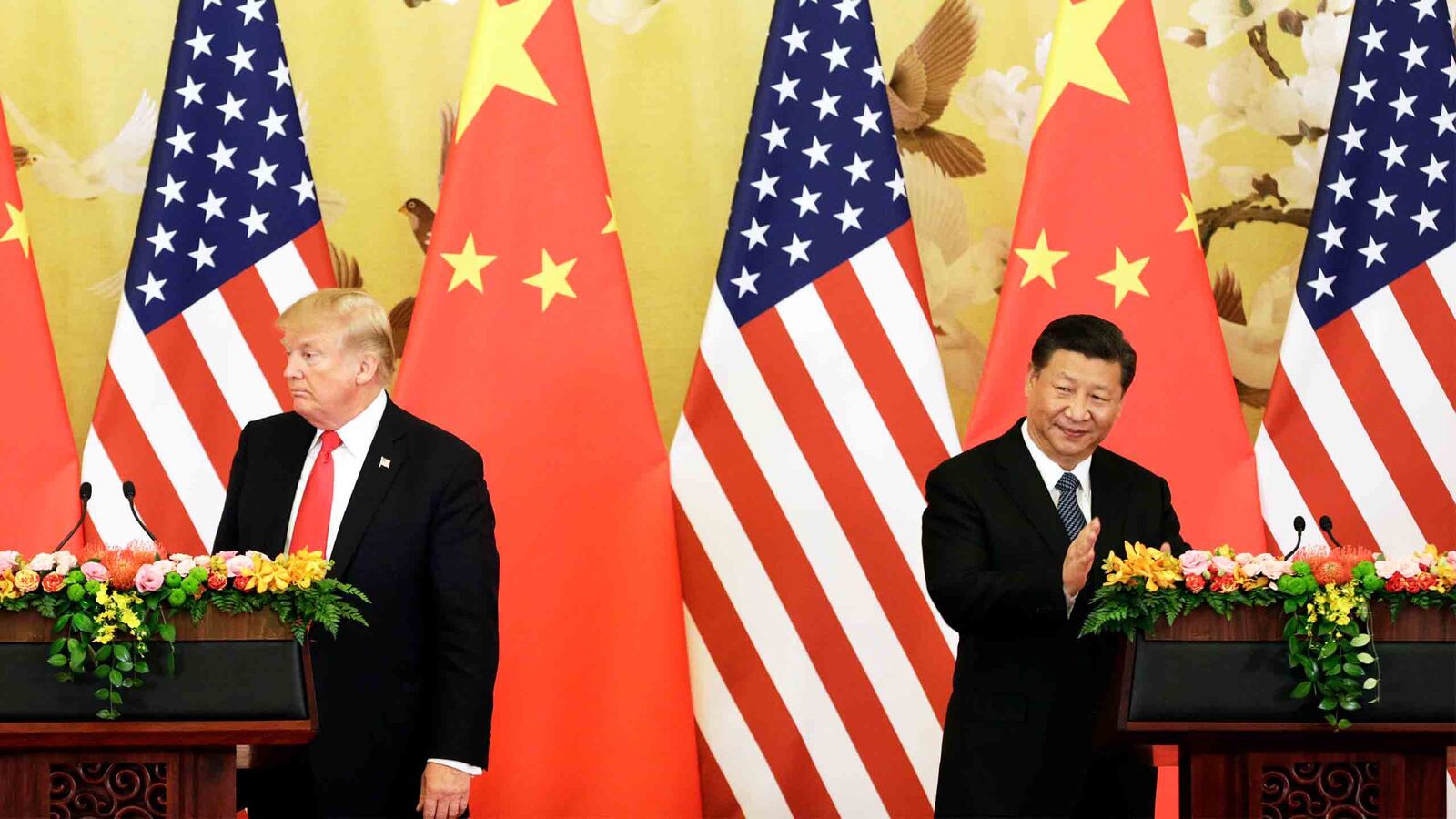

There are at least two narratives about trade and China on the American right. The first, nationalist narrative, has the President as its standard bearer today and individuals like Steve Bannon and Peter Navarro as its boosters. According to this crowd, schemers in Beijing are taking advantage of weak-willed or incompetent politicians in United States. As Trump puts it, China has been “taking advantage of us like nobody in history.” If we were not such idiots, the logic goes, we would be enjoying a trade surplus with the world’s number two economy. An assertive gesture—or three—will make China back off and restore balance.

A second, competing narrative comes from the traditional business wing of the Republican Party. According to it, China is less a threat to be combated than a capitalist ideal to be emulated. This narrative is exemplified by Mitt Romney’s 1998 comments as head of Bain Capital, describing a trip he made to a factory in China, where “5,000 Chinese, all graduated from high school, 18 to 24 years old, were working, working, working, as hard as they could, at rates of roughly 50 cents an hour.” These employees, Romney fondly recalled, “cared about their jobs; they wouldn’t even look up as we walked by.” The implication: American workers, in contrast, are under-motivated and overpaid and they—and more so, their unions—should be taken down a notch for the good of the country and themselves.

The labor movement and left are also divided over how to approach China and trade. Given the devastation that has been visited on the American industrial working class since the 1970s, one natural impulse is to try to turn back the clock to the situation before China was welcomed into the World Trade Organization or at least change the tenor of the relationship from the business-friendly approach pioneered by Bill Clinton and carried on since. In this vein, Trump’s steel tariffs were welcomed by the leadership of the AFL-CIO, as well as labor-aligned politicians like Ohio’s Sherrod Brown, and the president received grudging support from groups like Public Citizen and websites like The Huffington Post.

This impulse has its limitations. For many goods, the People’s Republic is only the last stop in corporate supply chains that stretch around the world, with, to take the example of an iPhone , design happening in California, cobalt coming from the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Chinese simply doing the final assembly before items are shipped to your neighborhood AT&T store (one analysis shows that if we adopt a value-added perspective, the U.S.-China trade deficit is a third lower than it appears in conventional accounting). The problem is less trade with any particular country than footloose capital. Moreover, emphasizing trade deficits often carries with it a certain jingoism and sits awkwardly with international labor solidarity.

A competing approach to China is exemplified by the anti-sweatshop movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s, which was driven by concern over the exploitation endured by precisely people like the “hard working” employees that Romney admired. Activists involved in this movement made clear that they were not demanding that the plants they investigated in the People’s Republic and elsewhere shut down and put their employees out of work—in fact, they criticized employers who “cut and ran” when faced with scandal. Instead, organizers called for improvements in working conditions, to be monitored by third parties or, better yet, empowered employees themselves (I was involved in related organizations). But achieving sustained progress on anything but the most egregious abuses, like child labor, proved difficult. Negotiated codes of conduct were hard to enforce. Media attention was fleeting.

Another tack is one that was taken in the first decade of the twenty-first century by some unionists, especially those affiliated with the Change to Win federation, who reached out to the Chinese Communist Party-controlled All China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), hoping that an alliance with this body could open a new front against companies like Wal-Mart. Early exchanges between representatives seemed promising. In some instances, they had the benefit of bolstering reformists in various branches of the ACFTU. But the organization as a whole generally treated its interactions with labor movements in other countries, the U.S. most certainly included, as opportunities to engage in diplomacy on behalf of China and the Communist Party, not to coordinate campaigns. And at the enterprise level, the ACFTU remained deeply entangled with management.

However, there is yet another, more promising approach. Over the past decade and a half, ties have grown between Chinese and American labor activists. Especially since the mid-2000s, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in China engaged on workers’ rights issues have expanded rapidly in number. These groups more or less take the form of the “workers’ centers” in the United States that have championed the rights of immigrant restaurant employees and other populations who have too often proved out of reach of traditional unions. In China, given the lack of representative unions, such organizations play a more wide-ranging role, acting alternately like law firms, cultural centers, and unions themselves. Directly and via Hong Kong intermediaries, Americans have connected with these groups (the anti-sweatshop movement was an early catalyst for dialogue). There have also been limited instances of direct engagement between workers in China and the U.S. themselves.

Maintaining such bonds will be extremely difficult going forward. Under the hardline leadership of current Communist Party General Secretary and Chinese President Xi Jinping, Chinese labor activists have increasingly been placed on the defensive. In 2015, dozens were swept up in a crackdown in the broader Guangzhou area and two NGO leaders, including the head of one of the country’s oldest worker organizations, were eventually put on trial. Various lurid accusations were made against these individuals, but their true crime in the eyes of authorities was clearly that they had begun openly helping workers engage in collective bargaining following wildcat strikes. The Chinese government has simultaneously become increasingly anxious about what it perceives as foreign meddling, passing a tough Foreign NGO Management Law in 2016.

Supporting Chinese workers will not bring jobs back to the United States. After all, if China is downgraded as a trading partner, some other country will likely replace it as the final assembler of cheap goods; this is already happening as firms move southward from China’s Pearl River Delta to Vietnam and Bangladesh. Nor should Americans imagine that they can instigate Polish-style worker-led regime change (and thinking of the relationship in those terms can be counterproductive). Chinese activists must meanwhile understand that U.S. organizers, pinned down at home by proliferating right to work laws and a looming Supreme Court ruling on public sector unions, will be limited in the resources they can bring to bear for the foreseeable future.

But if a full-scale trade war and increased tension between the U.S. and P.R.C. are in store, then building on sparks of solidarity between the two countries’ workers will be all the more important. By exchanging experiences and tactics, grassroots activists can more effectively confront their shared corporate and state antagonists. Equally importantly, they can begin to think through together what a more equitable global economy might look like. Deepened ties can help us deal with the challenges of the coming decades on a much better footing than we have enjoyed up until now.