Miroir, miroir, sur le mur, who is the best-selling French author of them all? Is it Jules Verne? Is it Alexandre Dumas? Perhaps it’s Hugo or Zola or Flaubert? Or could it be dear old Proust with his madeleines and cups of tea?

The mirror, were it a particularly switched-on sort of looking glass, would realize that this is a trick question. So far as we know, the best-selling French author of all time probably isn’t one person, but two. And these two people were never in the business of writing novels, but of making comics. They are René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo. They created Asterix.

Asterix is, as the Parisian publishing houses put it, un phénomène. More than 350 million copies of the books have been sold since the story first began in the comic magazine Pilote in 1959. There have been thousands of licensing deals signed, hundreds of translations produced, more than a dozen films released, and even a theme park constructed on the peripheries of the French capital. The country’s very first satellite, launched in 1965, bore the name Asterix. It’s a comic-book series that has gone all around the world.

Or has it? In truth, one particular country has always held out against Asterix. This proud and stubborn land is the United States of America.

U.S. sales figures for Asterix books are practically unknowable, so I shall have to compare Amazon rankings to support the point. The 36th canonical volume, Asterix and the Missing Scroll, was published on October 22 in Europe. At that time, it was the most popular book on Amazon.fr. On Amazon.co.uk, where I do my own shopping, it was the 356th most popular. Yet now, with the American release date only days away, it is languishing, as I write this, in 4,917th place on Amazon.com—and that’s probably only because of French expatriates.

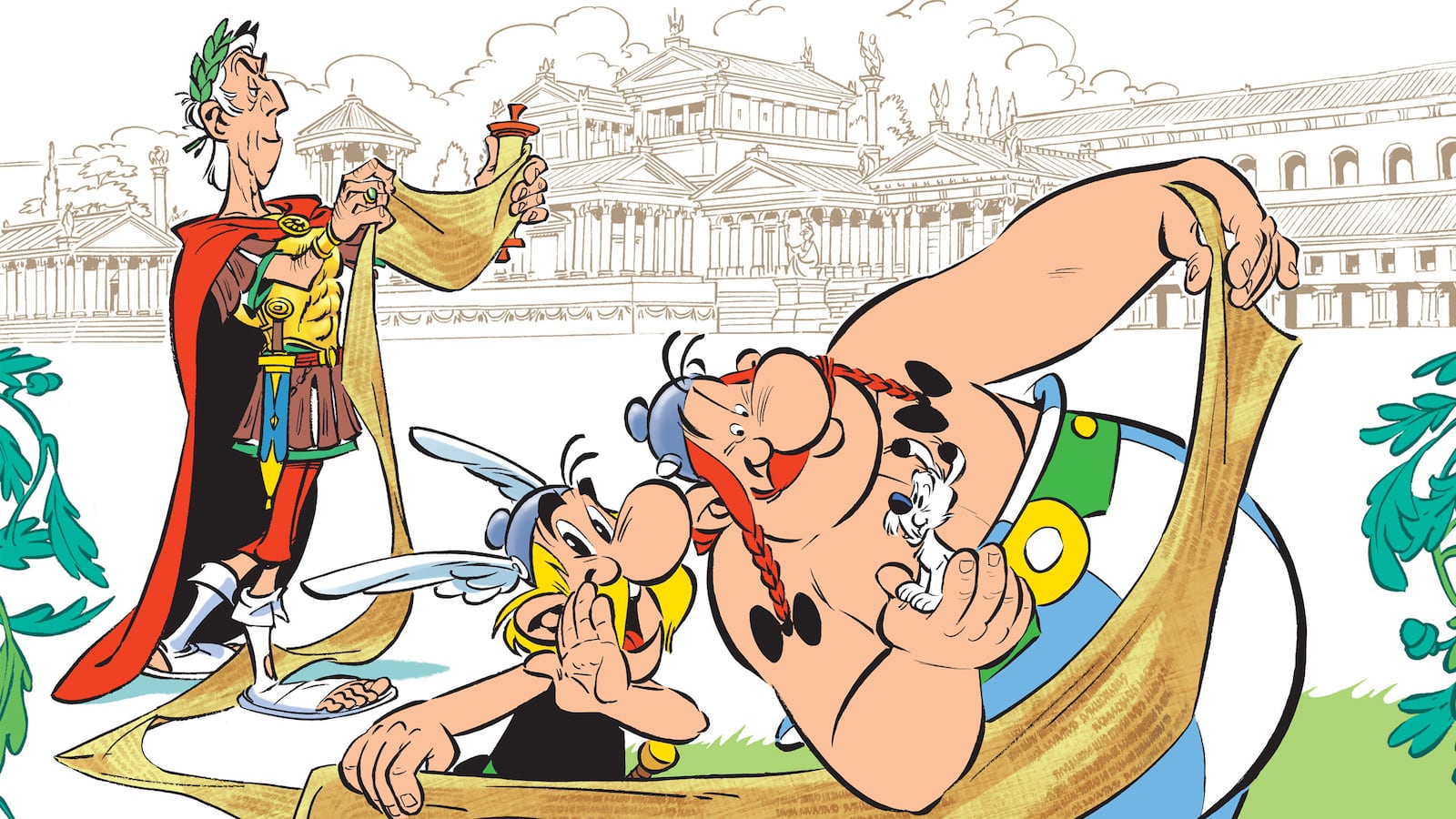

With that lowly ranking in mind, some introductions are in order. Asterix is the eponymously-titled story of a plucky warrior from Roman times. His village is situated in a northern corner of Gaul, or ancient France. Julius Caesar’s empire spreads all around, surrounding Asterix and his fellow villagers, yet they remain unconquerably independent from it. They have our hero and his best friend Obelix to thank for that—oh, and a magic potion, cooked up by the local druid, which makes its drinkers impossibly strong.

This was the setup that Goscinny, the writer, and Uderzo, the illustrator, came up with in 1959. It’s a setup that withstood Goscinny’s death in 1977, when Uderzo took over the typing duties, and it has since survived Uderzo’s retirement in 2009. The last volume to be published, Asterix and the Picts, was by the all-new team of Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad. The latest volume is their work, too.

The change of creators goes to show how adaptable Asterix is. There are things that we have come to expect: Romans getting beaten up, Obelix denying that he’s fat, a celebratory banquet at the end of the book, etc. But, as with all the best comic book series, from Batman to Usagi Yojimbo, so long as these tropes are delivered there are basically no other constraints.

Asterix’s adventures have taken him to Egypt and India and Rome itself. He has fought pirates, space aliens and, in the latest book, the redactions and obfuscations of a censorship state. He is fun for kids and clever for adults, as well as the other way around. In some ways, the Asterix books pre-empted Pixar: they are Disney, especially in look, but with a sharper edge.

So why has the USA remained unmoved? My best guess is Asterix’s historical setting. At its largest, the Roman Empire stretched from modern-day Portugal in the west to Iran in the east, from the lower reaches of Egypt in the south to the base of Scotland in the north. Yet never once did it cross the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Whatever-It-Was on the other side. Asterix and Obelix made this journey, of course, in Asterix and the Great Crossing—but not those imperialist Romans.

Where they did roam, the Caesars imprinted themselves on the land and on its inhabitants’ collective psyche. Look around you in Britain, and there’s probably one of their ruins somewhere. Their conquests are part of our island story. We are still taught their language in some of our schools. Which means that, when it comes to Asterix comics, we’re in on the joke in a way that Americans aren’t.

There is more recent history, too, that might explain the whys and wheres of Asterix. Here was a story about proud Gauls standing up to an invading force, appearing only 15 years after the Nazis had been rooted from French soil. Was this deliberate? Goscinny and Uderzo always denied having any grand political motivations. Their comic was originally intended, they said, as a light play on their countrymen’s attitudes towards the wider world, not as a serious statement about the wider world’s crimes against their countrymen.

But Asterix was always bound to be read differently. The first page of the first book, Asterix the Gaul, even encourages it. Its third panel shows two Germanic Goths being repelled from Gaul’s border at spear-point. “Gut! Ve go!” says one, in the sort-of-English translation. “So! But ve komm back!” adds the other. And komm back they did.

Until the Wikileakery of the latest book, that was as heavy as Asterix’s satire ever got. Generally, its punches are delicate enough to be counted as playful. The Brits boil all their food and drink warm beer. The Spanish take any opportunity to dance and writhe. And the Gauls, for all their heroism, can be pig-headed and prone to bickering. This is Goscinny and Uderzo’s version of the United Nations, and it has only one membership condition: laugh at yourself as you laugh at others. Even Germany has signed up. No other country, outside of France, buys Asterix books in greater quantity.

Few do more to keep these nations together than the translators who ensure that Asterix is published in languages other than its original French. It’s a tricky task. Much of the humor is based on puns, which don’t travel well across foreign borders. The only solution is to tailor each book for different countries. The druid who is called “Panoramix” in France, in allusion to the expansive effects of his potions, becomes “Getafix” in Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge’s English translation. He’s where Gauls go to get a fix.

The U.S. isn’t just excluded from this club by dint of its location and past. It also worked to exclude itself, in 1954. That was when the Comics Code was introduced to regulate all them awful pic-churr books that were corrupting the children of America. Vampires, blood, and cleavages were either out altogether or tightly restricted. Good, clean fun was in.

None of this harmed Asterix’s chances directly, but there were indirect consequences. The establishment of the Comics Code was the establishment of an American comics scene dominated by one thing above all others: superheroes. There might have been variety once, what with all the romance, horror, and crime comics on the stands back then. But these suffered disproportionately under the new regime. Only the superheroes were really able to stretch their muscles, and they left little room for anything else—particularly not some Eurohistory import from France.

But isn’t Asterix a superhero? The magic potion certainly turns him superhuman in an instant, just as the word “Shazam!” does for Billy Batson, or spinach does for Popeye. Yet the magic potion isn’t the point of Asterix. Asterix is the point of Asterix. He’s the little Gaulish warrior who can overcome the Romans with or without the potion, with his innate cunning rather than turbocharged fists.

One of my favorite moments in any Asterix comic comes towards the end of Asterix in Britain. Our hero has made a batch of the magic potion for his cousin’s British village, so that they can confront the better-equipped, better-trained and better-numbered Roman forces that march on their gates. Out charge the villagers! CRAAAASH! Thanks to the potion, nothing can stand before them. They triumph.

Except there was no potion. Asterix had simply stirred some leaves in hot water, and given that to the villagers instead. They had drunk nothing more magical than tea. Their victory actually came from their self-belief, their pluck, and some good, old-fashioned defiance.

These qualities now inflect French attitudes towards the U.S. and its ignorance of Asterix. For some, it’s a cause for pride that the land of Le Big Mac and Les Kardashians doesn’t get this comic. For Uderzo himself, it’s more complicated. The last book that he wrote and illustrated, Asterix and the Falling Sky, was done in tribute to his artistic inspiration, Walt Disney. Yet it also featured a race of superclones, patterned on Superman, whose leader is called “Hubs,” an anagram of “Bush.” It’s hard to know whether this was meant as a love letter or a hatchet job.

If it’s the latter, then let it be said that hatchets are there to be buried. Light a fire. Roast a boar. Raise a toast. And let’s feast under the starlight as they do at the end of every Asterix book. That little chap to your right is Asterix himself. The bigger gentleman—don’t call him fat!—is the great Obelix. And there’s Getafix, Chief Vitalstatistix, his wife Impedimenta, and all the rest. You should get to know them, stranger from across the ocean. You’ll like them.