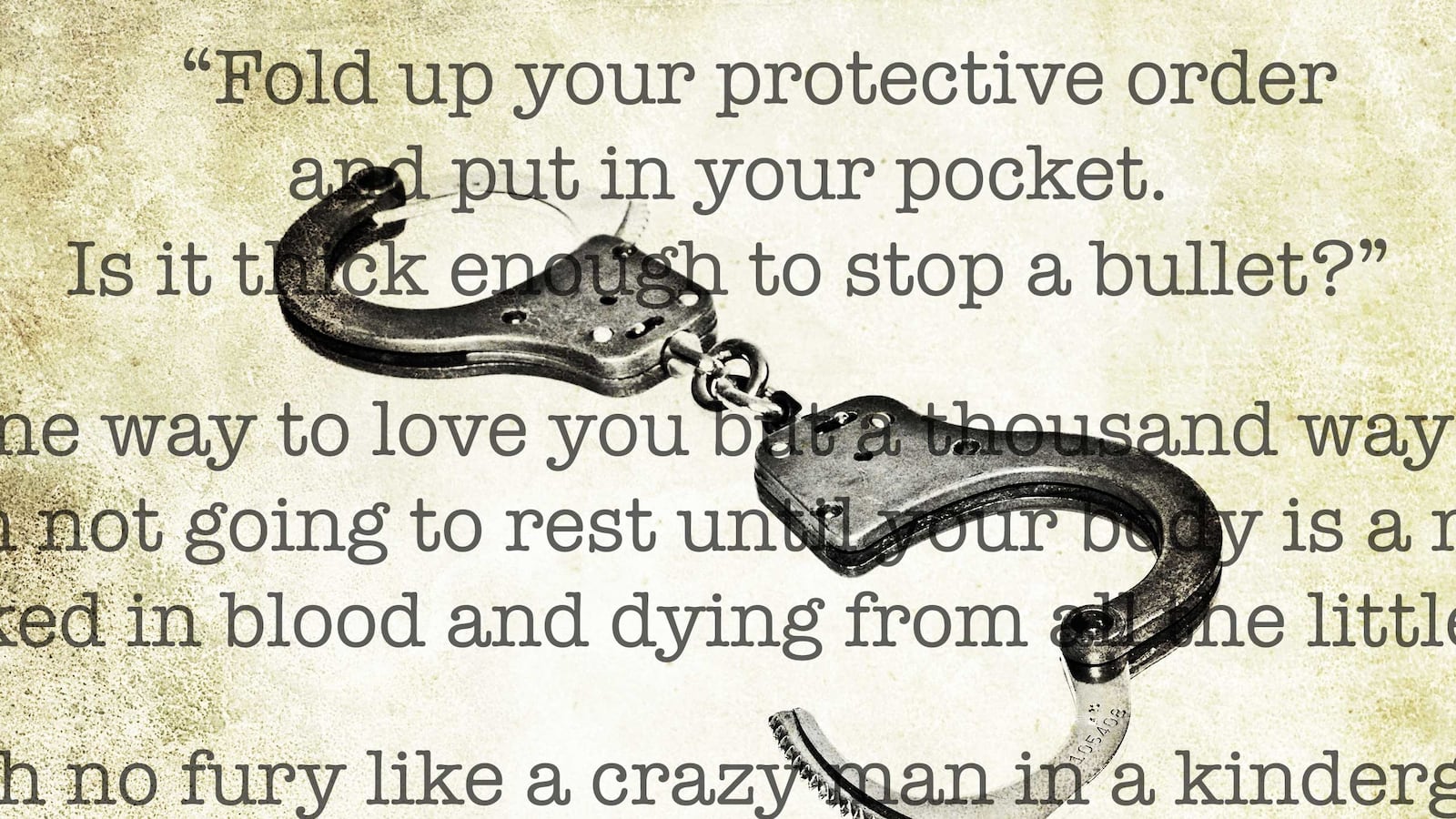

Last December, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in the case of Anthony Elonis, who, in 2010, began posting messages on Facebook, threatening harm to his estranged wife and a female law enforcement officer. Many of these comments were in the form of rap lyrics, and ended with the lines “Art is about pushing limits. I’m willing to go to jail for my constitutional rights. Are you?” Despite this disclaimer, Elonis was charged with multiple counts of communicating threats, found guilty at trial and sentenced to 44 months in prison.

The Supreme Court took the case on appeal to settle a narrow legal standard as to what constitutes a “true threat,” but more than anything, the Elonis case illustrates a disturbing trend in prosecutorial conduct: using rap lyrics as evidence that a defendant is guilty of a crime, is a gang member, or simply knows about criminal activity.

Prosecutors are doing this “because it works,” says Charis Kubrin, a criminology professor at UC-Irvine and co-author with Erik Nielson of the scholarly paper “Rap on Trial.” “Prosecutors are getting knowledge from others that this is an effective tactic,” says Kubrin, “and it is used when there is not a lot of physical evidence. Judges allow [the lyrics] in, they are extremely prejudicial, and they get convictions.”

Most of these cases involve the often violent posturing and role-playing common to gangster rap, and this hostility between law enforcement and hip-hop culture has a long history. The rise of hip-hop culture in the early ’70s, with its emphasis on break dancing, DJing, rap and other artistic endeavors, was often met with antagonism by law enforcement, which saw its practitioners as thugs and gang bangers. When rap began dabbling in social and political critiques—one of the earliest examples being “The Message,” the 1982 hit by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five—this confrontation heightened.

And when rappers like Public Enemy, Ice-T, and NWA began recording cuts dealing with their hatred of the criminal justice system, everything went into overdrive. In one particularly notorious example, FBI Assistant Director Milt Ahlerich, incensed by the lyrics in NWA’s “Fuck tha Police,” actually wrote a letter to the group’s label, Ruthless Records, which the company and First Amendment advocates interpreted as a threat and uncalled-for government interference. And in 1992, several law enforcement agencies and political candidates called for a ban of Ice-T’s song “Cop Killer.”

“For as long as there have been people of African descent on American soil, there has been hostility to their creative expressions,” says Nielson, who teaches hip-hop culture at the University of Richmond, and is co-author of “Rap on Trial.”

“You can trace that through spirituals, jazz, the black arts era, and you see it most acutely now with hip-hop,” he told The Daily Beast. “This antagonism stems in part from broader concerns about black speech, and black resistance. Black expression has always been regarded as a kind of threat.”

Prosecutors began using rap lyrics as evidence as long ago as the early 1990s, but only sporadically. According to Kubrin and Nielson, however, there has been a “meteoric rise” in the last decade, with more than 100 cases where lyrics have been entered as evidence in trials. A few of them include:

—Vonte Skinner, convicted in 2008 of attempted murder, based largely on a prosecutor’s use of his violent rap lyrics as evidence. His conviction was overturned last year.

—Deandre Mitchell, aka Laz Tha Boy, whose rap videos were used against him when he was indicted by a grand jury for two counts of attempted murder. Although there was no physical evidence linking him to the crimes, he spent nearly two years in jail before cutting a deal and was released with time served.

—Torrance Hatch, aka Lil Boosie, a Louisiana rapper charged in 2012 with murder despite there being no physical evidence. Prosecutors introduced his often violent rap lyrics into evidence, claiming they reflected reality. The jury didn’t buy it, and Hatch was found innocent.

Explaining the increasing use of this tactic, Andrea Dennis, a law professor at the University of Georgia who has written extensively about the issue, told The Daily Beast: “It’s just an increasing awareness of [introducing lyrics as evidence], prosecutors share information and trial tactics. And to the extent artists are able to make their art more publicly available, now you have more avenues for getting the information out, like the Internet and on YouTube, and they are getting the attention of prosecutors who are looking for this information.”

The demographic makeup of juries also figures into this phenomenon. At least one study suggests that all-white juries are more likely to convict black defendants than white ones, and another implies that prosecutors attempt to exclude younger people from the jury pool.

All of which plays into the ways in which older, white juries relate to rappers, many of whom are young, urban, and black.

“Generally, jurors who are not of the hip-hop generation are less likely to be familiar with rap, and to hold negative stereotypes,” said Clay Calvert, director of the University of Florida’s Marion B. Brechner First Amendment Project. “And then it becomes the defense’s job to hire people to try to educate the jury. But that might be difficult and expensive. And a lot of the African-American clients are probably being represented by public defenders who are overworked, and they don’t necessarily have the time to go out and hire experts who can say rap is not designed to be taken literally.”

“I believe most people don’t treat rap as a form of artistic expression,” adds Kubrin. “They assume it’s literal, it’s autobiographical. This rap thing reinforces what many people feel about young black men of color, that they’re threatening and dangerous. And when you hear their lyrics, you don’t hear that they’re doing this to posture.”

And it’s not like prosecutors, who may believe in the literal nature of rap lyrics, want to disabuse juries of their prejudices.

“In many instances they believe the lyrics in their particular case is literal,” says Dennis. “They indicate the state of mind of the defendant, even if it’s not a literal confession, it is factually accurate information about the defendant’s mindset. And many prosecutors look at it as a way to paint a picture of the defendant.”

“I’m willing to believe that some prosecutors and judges are simply ignorant of the conventions of rap music, and this is evidence of wrongdoing,” adds Nielson. “But in many cases, prosecutors are fully aware they are putting fiction on trial, and on some level misrepresenting it to secure a conviction. Ultimately they do want that prejudicial effect, and that is the purpose in these cases.”

A decision in the Elonis case is due any day now. But whether it will be narrowly crafted to define what constitutes a “true threat,” or broaden out to deal with the issue of rap lyrics as evidence, is up in the air. Is this tactic here to stay? Opinions are divided.

“Eventually it will take several cases of judicial pushback, where the courts or judges say this evidence is not admissible,” says Calvert. “Then it becomes tougher and tougher to get that evidence in.”

Adds Dennis: “There will not be any categorical prohibition; in most instances it will be a case-by-case determination in terms of admissibility. It will remain in the discretion of trial courts and given the particular facts of the case.”