The announcement that a second case of Ebola has been diagnosed in Dallas should provide an enormous sense of security for the worried general public—after all, the case has occurred not in casual contacts or even family members but rather, as predicted, in someone who cared for the patient in the late stages of his infection.

Against the sigh of semi-relief, though, is the shiver of fear as a collective chill runs down the spine of health-care workers in the United States, Africa, and Spain charged with caring for infected patients.

According to reports on Sunday, a female nurse who was involved in the treatment of Thomas Eric Duncan has been confirmed to be carrying the disease, making her the first case of Ebola transmitted in the United States. The case further complicates an already thorny question: Are health-care workers treating Ebola ever really insulated from the disease?

The spread of Ebola from patient to health-care worker is a new development here, but it has been raging in West Africa for months. In the World Health Organization’s most recent report, it is identified as “an alarming feature of [the] outbreak.”

As of Oct. 8, the WHO reported 8,376 cases worldwide, of which almost half—4,024—had died. Among medical personnel, there were 416 confirmed cases and 233 deaths, a mortality rate of more than 56 percent. While the number of health-care worker deaths may seem small in comparison to the overall death toll, just three physicians are covering six of the hardest-hit counties in Liberia, according to the CDC. The high death rate among doctors and nurses could weigh heavily on prospective volunteers.

In some ways, the concept of a health-care professional contracting the disease from a patient in the United States is more alarming. In West Africa, most medical facilities lack basic supplies, meaning many health-care workers there who contract the disease probably never had proper protective gear in the first place.

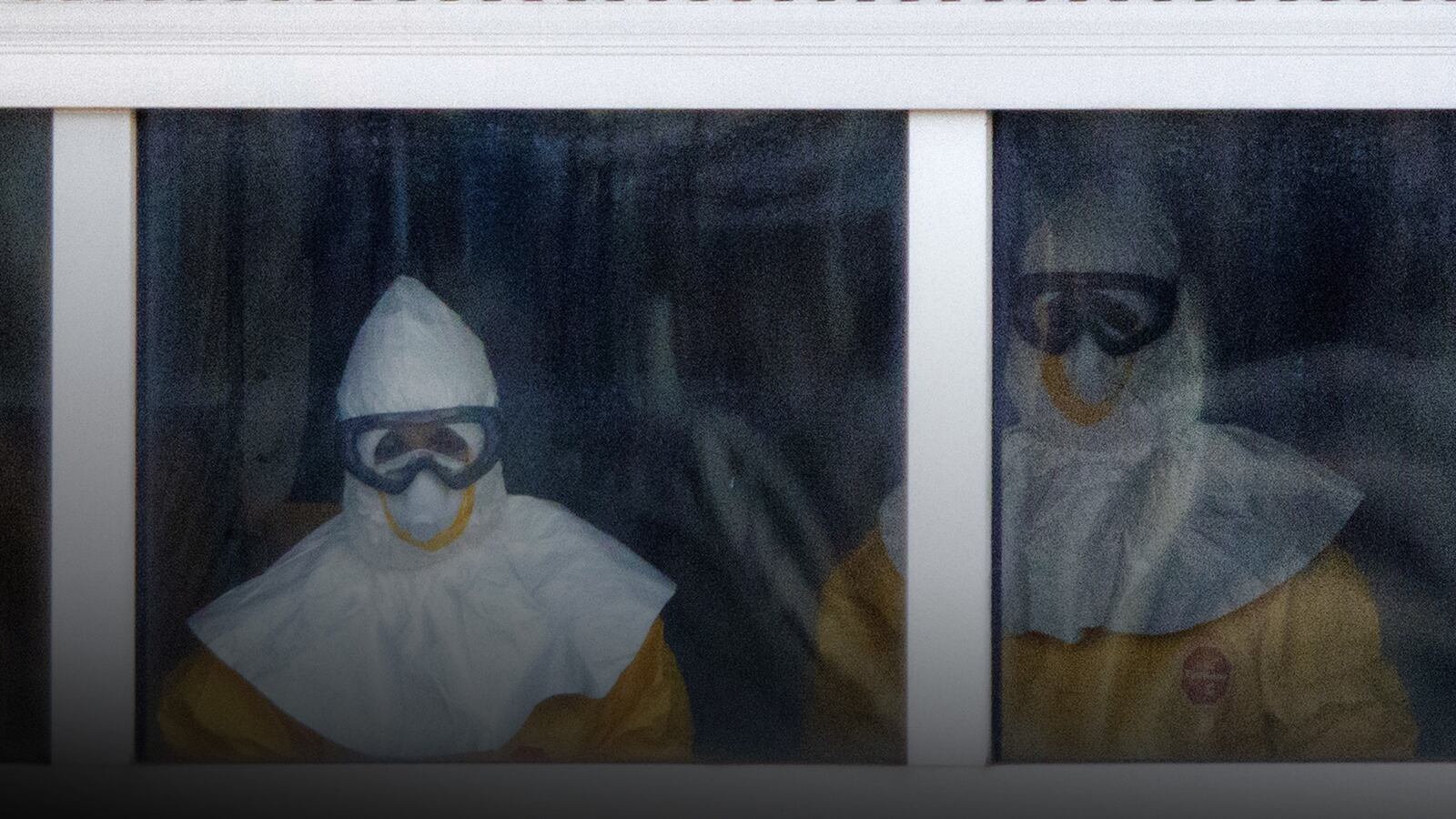

In the United States, with its endless supply of gloves, masks, boots, and gowns, transmission of the disease from patient to health-care worker implies something different. Personal protective gear is only as effective as the protocol for using it.

The Dallas nurse, who officials confirmed was wearing gear, was allegedly treating Duncan on his second visit to the ER, where he was hospitalized and diagnosed before eventually dying.

This detail is extremely important.

Though much remains unclear about Ebola and transmission, we do know that any virus is much more contagious when high amounts of virus are concentrated in the sick person’s blood. It is likely, therefore, that Duncan was much more contagious further into his illness, making transmission increasingly likely.

Studies done two decades ago about a different virus that was transmitted too frequently to health-care workers three decades ago, HIV, make this point very convincingly. “Source cases” with very high HIV viral loads were six times more likely to transmit HIV to health-care workers.

This may have played into Duncan’s case, which has left officials in Texas such as Health Resources chief clinical officer Dan Vargas, scratching their heads. “We’re very concerned,” Vargas told the press, “[though we’re] confident that the precautions that we have in place are protecting our health-care workers.” In other words, the protocol works, but many people’s ability to follow it exactly—really exactly—may pose a substantial challenge.

In a press conference Sunday morning, CDC Director Thomas Frieden touched on this concept—and suggested that more care must be taken in the later stages of the disease. “It’s deeply concerning that this infection occurred,” Frieden told the media. “Infections only occur when there’s a breach in protocol. We know from many years of experience that it’s possible to care for [patients] with Ebola safely without risk to health-care workers. But we also know that it’s hard, that even a single breach can result in contamination, and one of the areas that we look at closely are things like how you take off the gear that might be infected or contaminated.”

Failing to follow proper protocol significantly increases the danger as the viral load in a patient’s blood rises, a product of the infection’s later stages. With knowledge of this, Frieden and the CDC are suggesting that care for patients in the late stages of the disease be limited solely to “essential procedures.” Kidney dialysis and respiratory intubation, two procedures performed on Duncan, are procedures unavailable for patients in West Africa that might that pose unanticipated risks to health-care workers.

What this means for the hundreds of health-care workers in Atlanta, Omaha, and in Dallas is both simple and very complex: Caring directly for a patient with late-stage Ebola is very dangerous. It also means that workers in the United States, like those in Spain, may hesitate to work around such patients. Western workers may no longer feel safe volunteering in West Africa. For the United States and other nations, which have just begun gearing up for a medical intervention there, this is a potentially huge setback.

In the welter of worry, though, it is important to consider the experience at the two sites in the United States with special training and recent experience treating patients: Emory in Atlanta and the Nebraska Biocontainment Center in Omaha. These sites, where health-care workers go through training and more training, have safely cared for five patients, including the first two, Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol. For Ebola care, as with all other things, it is likely that practice makes perfect—and that only perfect is good enough.

On Wednesday of last week, a government agency sent out an email detailing the doctors, nurses, and infection specialists needed to make up each of the 24-person medical teams that will deploy to Liberia. Any sliver of appeal the $8,000-$10,000-per-month jobs—slightly above average for nurses—may have held initially may have disappeared.