Doug Olson was 49 years old with a wife and four kids when he was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 1996. His initial treatments were pretty successful, but by 2010 almost 50 percent of his bone marrow was cancerous again.

That’s when he enrolled into a clinical trial of a new cancer therapy led by his oncologist, David Porter from the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, together with one other patient. The experimental treatment, also known as CAR T-cell therapy, would tweak Olson's own immune cells to spot and kill leukemia cells, and reintroduce them into his body through blood infusion—something that previously showed promise only in trials on mice.

Olson started physically feeling the results after just a couple of weeks. “That’s when Dr. Porter came into my hospital room and he announced, hot off the press, that 18 percent of my white cells were CAR T-cells,” Olson said during a press conference Tuesday. “I will tell you that moment, I was absolutely convinced that this thing was working and that I was gonna be OK.”

The next week, Porter told Olson the clinicians couldn’t find a single cancer cell in his body.

It’s been more than 10 years now, and Olson is still cancer free.

In a peer-reviewed study published today, in the journal Nature, Porter and the clinicians who followed Olson’s journey document the experimental treatment and its results. The findings show that even after ten years, Olson and the other patient have remained cancer-free thanks to CAR T-cell therapy—validating its incredible efficacy and opening the door for its use in many more cases of leukemia and other cancers in the future.

“It was an exciting new therapy, but we've all been involved in many, many, many, many different new therapies and it is rare to hit on something to work so dramatically,” said Porter, lead author of the new paper. “The responses have been beyond our, certainly my, wildest expectations.”

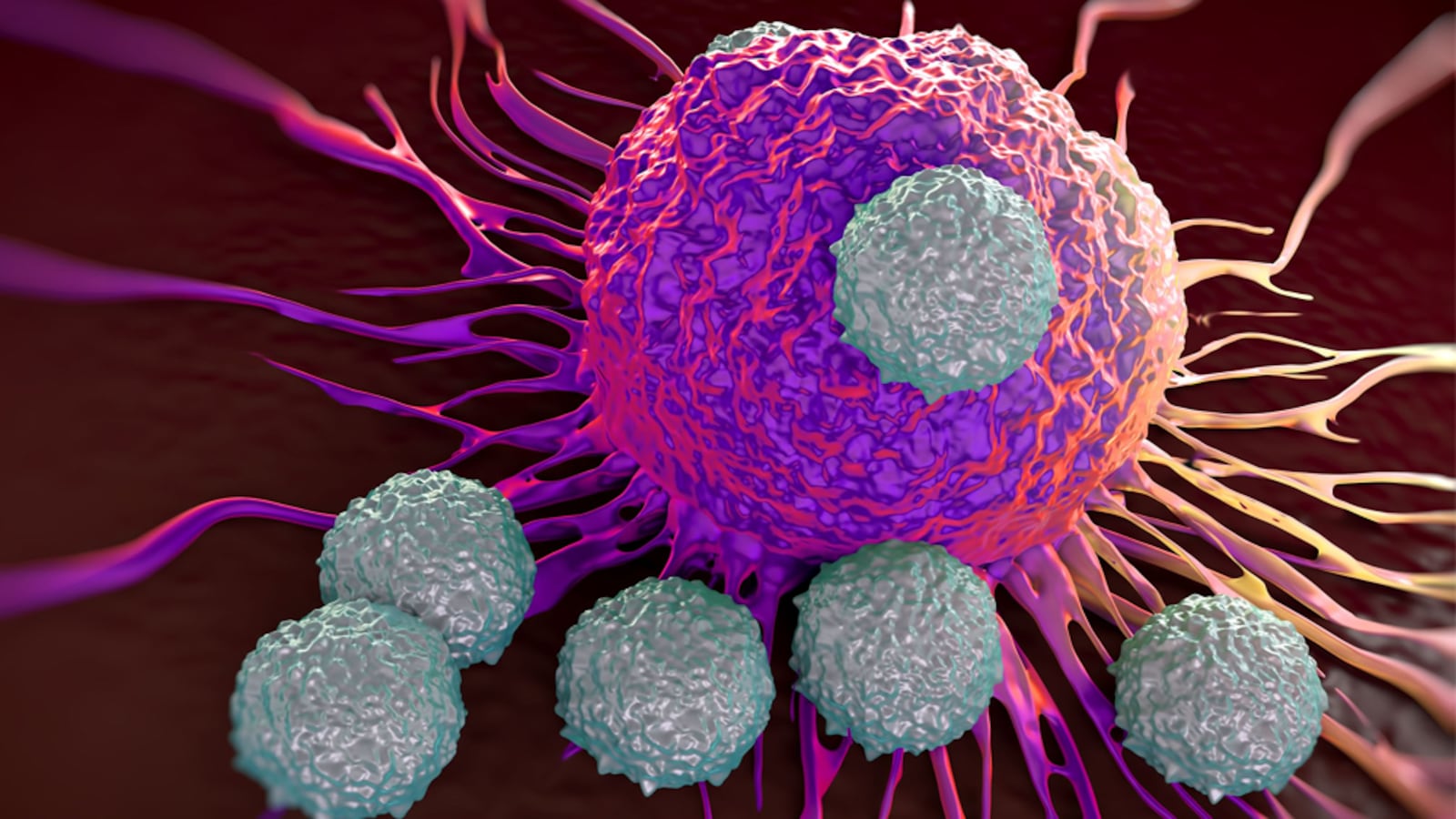

T-cells are an essential component of the immune system. They can both direct other immune cells to attack invading pathogens, as well as kill pathogens themselves. T-cells live for a very long time and can form a lifelong memory of what they’ve recognized before, like from viral exposure in childhood.

In CAR T-cell therapy for cancer, a patient’s own T-cells are collected and genetically engineered to produce a molecule called a Chimeric Antigen Receptor, or CAR. These CARs enable the T-cells to identify cancer cells with a laser-eyed focus and eliminate them. Millions upon millions of CAR T-cells are made in the lab, and then re-inserted in the patient through a blood infusion. In theory, CAR T-cells should be able to swoop in and clear out tumor cells with extreme precision and speed. And since they retain such good memory and can circulate in the body for a long time, they should be able to prevent the same cancer from popping up again.

But Porter and his colleagues were stunned to see the therapy prevent a resurgence of cancer cells for such a long time in this latest study, given the high rate of relapse for leukemia. They suspect CAR T-cells evolve within patients over time to learn better ways to hunt down tumor cells.

“[CAR T-cells are] wearing multiple hats,” Joseph Melenhorst, a UPenn immunologist and co-author of the new paper, told reporters Tuesday. “We've called these cells, you know, a living therapy. The major finding that shows in this paper is that 10 years down the road, you can find them, but they have evolved.”

The researchers don’t know if there are still leukemia cells forming in Olson’s body and simply being rapidly killed by the CAR T-cells on patrol; or whether there has truly been an absence of cancerous activity in the patient since 2010. What they do know, however, is that when Olson’s CAR T-cells were taken out of his body and confronted with leukemia in the lab, they were still able to kill.

David Porter

Courtesy UPennSince that clinical trial in 2010, CAR T-cell therapy has now been FDA approved for six different indications, and acute leukemia is treated routinely with this therapy worldwide. But these are the first results to establish how long-lasting it could work for the tens of thousands who’ve already been treated.

The major barrier for patients, unfortunately, is price. CAR T-cell therapy can cost anywhere from $300,000 to $500,000. Researchers are trying to create less expensive over-the-counter therapies that have the same approach, with cells made from other donors in large amounts.

Then, hopefully, it’ll be possible to expand this therapy to tackle solid cancers too, like breast cancer, lung cancer, or pancreatic cancer. Trials are currently underway, but the results so far haven’t been particularly encouraging.

And although the two cases explored in the new paper have had very positive outcomes, the long-term effects of CAR T-cell therapy still need more extensive study. Some patients report worse side effects because CAR T-cells do have some unique toxicities. Even Olson’s positive outcome was tempered by a bout of tumor lysis syndrome, where the rapid destruction of cancer cells leads to an adverse immune reaction and causes flu-like symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and joint pains.

And there are some instances where the CAR T-cells lose some of their efficacy, especially in trials against solid tumors.

“The biology of long-lived persisting CAR T-cells isn’t fully understood,” Sara Ghorashian, a CAR T-cell researcher from University College London who was not involved in the study, told The Daily Beast. It’s not entirely clear yet why some patients will see CAR T-cells that last for years, while others might experience fading efficacy in less than six months.

A host of unknown factors could be at play, and Ghorashian cautioned against extrapolating the findings to all CAR T therapy settings.

Still, within the span of a decade, CAR T-cells have broken out as a game-changing form of cancer treatment. And findings like Porter’s and his colleagues’ will only fuel more efforts to learn more about how this therapy works and how we can make it accessible to more patients who are fighting for their lives.