Books

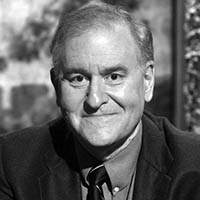

Photo Illustration by Erin O’Flynn/The Daily Beast/Warner Bros, Getty Images and Courtesy of the University of Wyoming

‘Casablanca’ Once Had So Many Songs It Was Almost a Musical

‘romantic crap’

No one at Warner Bros. had the slightest idea that “Casablanca” would one day be called the greatest movie ever made.

Trending Now