The attack was swift and violent. It was a few hours before dawn in San Salvador when three armed men broke into the headquarters of Probúsqueda—an El Salvador civic group dedicated to tracking down disappeared children—and went to work. Holding three employees at gunpoint, the raiders rifled drawers, plundered computer files and set the offices of the non-profit on fire.

This was no random act of vandalism. The smell of gasoline still laced the air when the forensic teams arrived on the scene hours later. And though police investigators have yet to discover who launched the assault, no one in this war-scarred Central American nation missed the underlying meaning of the rampage.

The Nov. 14 attack came less than 72 hours after an historic hearing at the Salvadoran Supreme Court. There, eyewitnesses represented by Probusqueda told the high court of the day 30 years ago when government troops stormed their village, shooting to kill. The witnesses, all children at the time, lost their parents in the 1982 massacre but survived to tell the tale. After years of uneasy silence, their harrowing stories—and many more like them—are becoming public for the first time, shedding light on an era that many powerful Salvadorans would prefer to forget. “There is clearly a part of society that seeks to destabilize the country by these means, and we do not yet know who they are,” the bishop Martín Barahona, of the Anglican-Episcopal Church of El Salvador, declared.

Adding credence to the menace was the move by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Salvador last month to close down Tutela Legal, a legal office that keeps a data bank of some 50,000 documents related to human-rights abuses committed during the Salvadoran civil war. Tutela Legal’s archives have become crucial evidence in the trials of former military men, many of whom have been brought to trial in the United States.

For over a decade, between 1979 and 1992, El Salvador was a central battleground in the Western hemisphere’s version of the Cold War, when security forces—often backed by the United States— fought determined Marxist guerrillas across the Central American isthmus, with repercussions from Moscow to Patagonia. An amnesty law in 1993 drew a cloak over that bloody era that saw 75,000 Salvadorans slain, on the belief that society could recover only if its wounds were left to scar and blood enemies agreed to look the other way. The assault on Probúsqueda was a brusque reminder of how thin that conviction ever was, and a troubling sign that the old Central America maybe never went away after all.

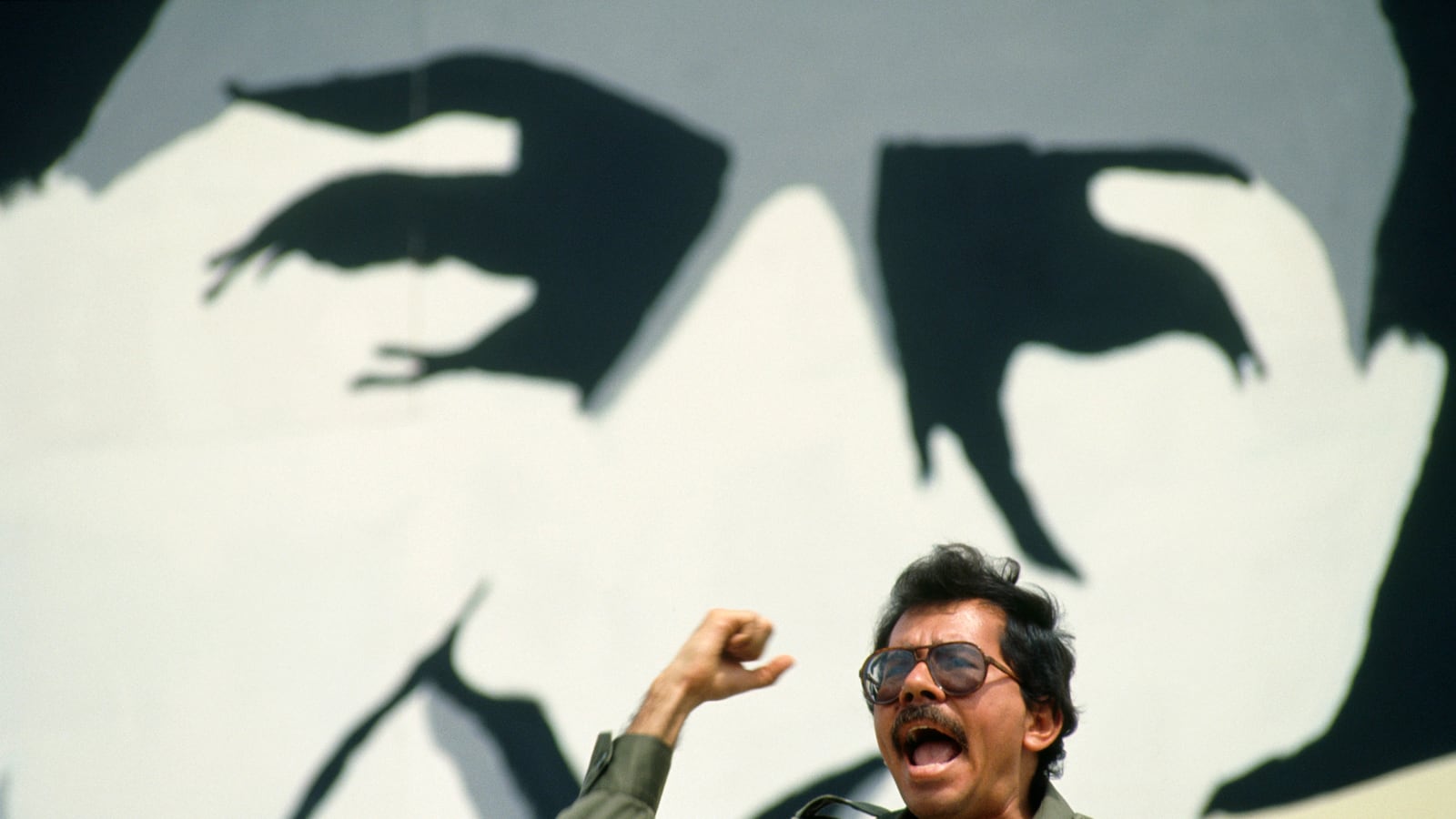

This worry is alive not just in El Salvador. In Nicaragua, former Sandinista guerrilla Daniel Ortega laid aside his Kalashnikov and embraced the ballot box, parlaying his image of freedom fighter into votes. Now in his third presidential term, he has turned the Nicaraguan bureaucracy into a bully pulpit, issuing edicts, stifling the independent press and strong-arming political opponents—not unlike the very military men he confronted as a freedom fighter. And in a plot twist worthy of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Ortega’s own stepdaughter has accused the former Sandinista of abusing her sexually when she was a child.

In Guatemala, memories of the dirtiest chapter of Central America’s dirty war came rushing back this year when former president Efrain Rios Montt was brought to trial on charges of genocide for the key role he played during the 36-year-old conflict that took 220,000 lives. But generalissimos don’t go down quietly and the ex-strongman, backed by loyal soldiers and expensive lawyers, maneuvered to annul a guilty verdict in the Constitutional Court earlier this year and forestall a retrial until 2015. Now human rights group despair that the 78-year-old Rios Montt will ever be made to pay for his alleged crimes.

And yet, such incidents, dramatic as they may be, seem less like a return of Central America’s bad old times of dictatorship and guerrilla insurgency than they do a dull echo of a bygone era. As El Faro, El Salvador’s leading digital publication, wrote in a lead editorial about the attack against Probúsqueda: “The message was sent in the style of the old days. But the old days are gone.”

Clearly the raid on the advocacy group, which has worked to trace children whose parents were killed by the military, was a warning to those who would stir the memory pot. Likewise, the hasty shuttering of Tutela Legal, with its potentially damning archives in the cases of the “disappeared,” was widely interpreted as a response to the growing climate of intimidation in El Salvador.

But the world has turned since the Latin Cold War. Civic groups are speaking up and demanding that there can be no reconciliation can take place until the truth is told. Courts in El Salvador and Guatemala are reviewing the silence of the amnesty law. Backing them is the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which ruled last year that “gross violations of human rights” were not shielded by amnesty.

The decision created a precedent for national courts to prosecute culprits of heinous acts such as the 1981 El Mozote massacre, perhaps the worst in Latin American history, in which Salvadoran troops killed nearly 1,000 people in six villages, including at least 450 children.

For the first time, the goons and martinets who wrote the rules in Central America are seeing their day in court. Even onetime untouchables like Rios Montt must now answer to a judge and jury for their alleged “crimes against humanity.”

Sure, brutes and warlords still roam the region, but the worst enemies no longer wear uniforms or wield guerrilla manuals. The good news is that the Armed Forces have mostly retreated to the barracks. The bad news is that today’s oppressors are more sophisticated and wield more clout than ever. Many are leveraging their popular mandates to garner superpowers, such as Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro, whose congressional majority has just handed him the right to rule by decree for the next year. Elsewhere, Generalissimos have given way to narcotraficantes and their transnational criminal operations, who have intimidated authorities, bought off judges and cops, and turned Central America into a killing ground rivaling the days of the dirty wars.

Latin America is the most “insecure region” in the world, with more than 10 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, the threshold for “epidemic” violence, according to the United Nations. Between 2000 and 2011, as violent crime fell most everywhere else, the Latin America murder rate rose 11 percent. A total of 1 million people were murdered last decade.

Not surprisingly, three of the most violent nations on the planet are in Central America, with Honduras and El Salvador topping the list. Despite the return of free elections, the region is still hobbled by political corruptions, frail democratic institutions, and fratricidal politics. Tin horn dictatorships have become tin horn democracies. All the better for international drug cartels whose capos would rather milk the state than overthrow it. That’s the kind of power that the old generalissimos only dreamed of.