Get more news and opinions in the twice-daily Beast Digest newsletter. Don’t miss the next big story, sign up here.

After weeks of speculation, former President Donald Trump was indicted on Thursday. While we don’t yet know specific charges, reports indicate they’re directly tied to his payoff to a woman with whom he had a brief affair.

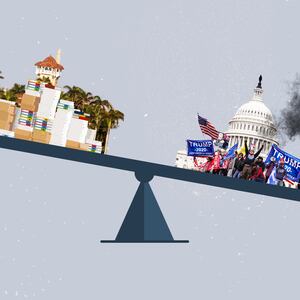

Donald Trump’s legal woes are many, to put it mildly. He is currently the subject of grand jury investigations at both the state and federal level. Many of his close associates have already gone to prison for various offenses. It feels like a safe bet that he’ll be facing another criminal case within the year.

But the New York state-level case, at least from what we know of it, does not concern inciting a riot, demanding the Georgia secretary of state “find” more votes for him, pressuring the vice president to violate the Constitution—or even the New York tax charges for which the Trump Organization and its CFO were both recently convicted.

Instead, the case is supposedly based on paying hush money to a porn star seven years ago.

As many skeptical experts were quick to note—including many who are no fans of the former guy—this is an extremely eyebrow-raising proposition. With the grain of salt that we haven’t actually seen the details yet, it is what The New York Times charitably called “a novel legal theory.” The reality is that’s an extraordinarily flimsy case, a Rube Goldberg device of tenuous leaps.

Republicans were quick to rally around the line that such a prosecution would be frivolous and blatantly politically motivated. It was easy for them to say that because it’s true.

Just the Facts, Ma’am

In October 2016, Donald Trump paid adult film actress Stephanie Clifford, a/k/a Stormy Daniels, $130,000 to sign a non-disclosure agreement about an alleged affair they’d had in 2006. The transaction was facilitated by Michael Cohen, Trump’s personal attorney and “fixer.” These basic facts are not disputed.

A presidential candidate paying off a porn star weeks before the election is certainly not the stuff of ideal statesmanship. Add it to the long litany of things that would have sunk anybody else’s political career. For Trump, it’s pretty far down the list.

Paying somebody to sign an NDA, much less under the circumstances here, obviously doesn’t look good. By definition, it’s something you’d prefer to keep out of the public eye. But it’s not illegal.

Stormy Daniels speaks during a ceremony in her honor in West Hollywood, California on May 23, 2018.

Mike Blake/ReutersThe problem, supposedly, arises out of the fact that Trump was running for president. As such, his campaign was subject to all the usual federal campaign finance laws, including individual contribution limits and reporting requirements. And here the case for criminality takes its first problematic leap.

The theory goes that paying Stormy Daniels was really a campaign expense, just like buying TV ads or hiring a pollster or paying your campaign manager. There has been widespread confusion on this point. A common misunderstanding is that Trump used campaign funds to buy Stormy’s silence and that’s the problem. That’s not an unreasonable intuition, because that would be obviously improper. But prosecutors have actually advanced the opposite interpretation: that Trump should have used his campaign to pay Stormy.

So What?

Obviously, Trump’s motives here were highly political, especially given the timing. But just as obviously, he had personal motives (to avoid embarrassment, or his wife finding out, or whatever) as well as business interests (Trump’s business is indistinguishable from Trump as a public figure). Disentangling these motives to say the law clearly mandates treating this matter as one or the other is an absurd exercise. And the law doesn’t clearly say that.

This same theory, under similar but more egregious circumstances, was applied in the prosecution of former senator and vice-presidential candidate John Edwards. Edwards had arranged for a wealthy friend to provide money to his mistress, with whom he had a child. This, supposedly, amounted to extracting a de facto campaign donation in excess of the limits and without reporting it. The jury wasn’t convinced, acquitting Edwards on one charge and producing mistrials on the rest. The Department of Justice chose to accept defeat and not retry the case.

There’s something patently absurd about treating such matters as legitimate campaign expenses. Candidates still have their own personal and business capacities outside of their FEC-regulated campaign committees. They’re allowed to enter into contracts, execute transactions, and other normal business without routing everything through their campaign. In fact, the law forbids treating improper personal expenses as campaign expenses. Others have gotten in trouble for that, including other cases involving sex scandals and extramarital affairs.

As unsympathetic as politicians covering up their affairs are, the legal interpretation that doing so amounts to a campaign finance violation creates an untenable Catch-22. Something which isn’t itself illegal becomes effectively banned because the government provides contradictory rules on how it’s to be treated for book-keeping purposes. Any of the multiple options might get you prosecuted. The whole thing is Kafkaesque, an affront to the rule of law and due process.

Weak Links

As many have pointed out, Michael Cohen went to prison for his role in all this. Because it was allegedly an illicit campaign expenditure, Cohen’s role as an intermediary amounted to making a straw donation in excess of the limits. He spent the money paying Stormy and Trump then comped him for it. This would be illegal if the money in question had been an actual campaign donation, because $130,000 is more than any one person (except the candidate themselves) is allowed to donate.

Michael Cohen, former attorney for former President Donald Trump, arrives at the New York Courthouse in New York City on March 15, 2023.

Eduardo Munoz/ReutersCohen, however, never raised any of these arguments. He waived them all as part of his plea deal. And why did he take a plea deal? Because federal prosecutors had him nailed on unrelated tax fraud and other crimes. Even if he had beaten the campaign finance charge, he would have gone to prison for a much longer time if he’d gone to trial on the tax charges and been convicted, as he certainly would have been.

It was an exercise in coercive plea bargaining of the sort that’s endemic in our criminal justice system. On top of which, it worked out much better for Cohen to have been convicted of something Trump-related than to face the same sentence or worse for matters Trump had nothing to do with.

Coercive plea bargaining tactics won’t work with Trump. He has no incentive to plead guilty to charges he thinks he can beat, and in this case, he’s not wrong to think he can beat them.

Cohen pled guilty to a federal felony on the allegation that he had violated federal campaign finance laws. So what does the state of New York have to do with it? Here, things begin to get even more doubtful than the already-dubious campaign finance theory.

In New York, it is a misdemeanor to falsify business records. It is a felony to do so to conceal another underlying crime. Trump accounted for the Stormy Daniels matter as “legal expenses.” Which is frankly a much more plausible categorization of it than calling it a campaign expense. But the argument goes that Trump falsified his business records to conceal that underlying crime, which makes it a New York felony.

Even accepting this interpretation (which raises additional complicated questions of to what degree state officials can enforce federal laws), there’s a threshold matter which could make it all moot. The statute of limitations is five years (only two years for the misdemeanor). This all happened in 2016 and 2017.

Can’t get enough from The Daily Beast? Subscribe to the twice-daily Beast Digest newsletter here.

To get around this requires relying on a dubious, little-tested provision of state law that tolls (extends) the statute of limitations whenever somebody is “continuously” out of the state. Trump did not officially switch his legal residence from New York to Florida until 2019, but in the years prior he spent relatively little time at Trump Tower. Partly because he was more often staying at his other properties, but mostly because he was in Washington, being the president.

State courts have offered differing interpretations of how this law works, and it’s rarely been tested. In principle, the theory behind tolling the statute of limitations is to exclude time when somebody is beyond the reach of the law through their own actions.

Donald Trump was not a fugitive these past seven years. He was not hiding in a cabin in the woods somewhere. He was not hard to find. Even if it’s correct, it is an archaic presumption that somebody in another state is meaningfully unreachable by state laws. States issue arrest warrants for people in other states all the time. They are routinely carried out, followed by a largely pro forma rubber-stamp extradition process. This process even has its own clause in the Constitution.

Nor does alleged presidential immunity work. Even if Trump had total immunity while in office, a speculative and highly disputed constitutional theory, then the likeliest result is not that he couldn’t be indicted. It would be that the indictment is held in abeyance until he’s available to stand trial after leaving office. There’s no reason New York couldn’t have brought the indictment in a timely manner, as our legal system requires for good reasons.

The Wrong Case

Any one of these points would be enough to make a typical prosecutor wary. Stringing together so many weak links is bordering on absurd, especially in the matter of such a long-ago triviality.

On many potential charges against Trump—for trying to manipulate Georgia’s election results or for inciting Jan. 6 or for hoarding top secret documents—it’s easy to make the case that anybody else would likely be prosecuted under the same circumstances. He’s not being unfairly targeted, he’s being treated fairly as a citizen under the law just like any other, exactly as he should be.

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, whose office is investigating $130,000 paid in the final weeks of former President Donald Trump’s 2016 election campaign to Stormy Daniels, in New York City, March 27, 2023.

Amanda Perobelli/ReutersThat argument is not applicable to Stormy-gate. No other person under the same circumstances would be prosecuted on this weak a case. That holds even if additional related charges (such as obstruction of justice and the like) are also charged, a distinct possibility given the large number of charges being reported. It’s possible such charges would be on stronger legal ground, covering more recent conduct under more clearly established and commonly used laws. We will be in a much better to judge when the indictment is unsealed. But it would still be extremely unusual to bring those sorts of charges on a matter that would have never even been investigated if it was anyone else.

It is plainly, undeniably about going after Trump because he’s Trump. In doing so, it undermines the broader case for prosecuting him on much more important and much more legally sound charges. All this for a case which would, even if it overcomes all these hurdles and secures a conviction, almost certainly result in a slap on the wrist sentence with no time served.

The example of Al Capone has come up a lot. The notorious mobster was obviously guilty of much more serious crimes, but he was ultimately sent to prison for federal income tax evasion. This is mentioned as if it’s a clever and admirable precedent and reasonable comparison. It’s not.

Al Capone’s tax evasion was, in the first place, much more serious and much more closely related to his other crimes in running an organized criminal enterprise.

Even so, we should not look kindly on the idea that if the government can’t make its real case against you, they can always just get you on some other technicality. We should be especially cautious about that when our laws are so numerous and vague that the average person commits countless felonies all the time. Reasonable and consistent standards of prosecutorial discretion are part of the rule of law, too.

Prosecuting Trump over Stormy Daniels is not like convicting Al Capone of tax fraud. It’s more like prosecuting Al Capone for a decade-old unreturned library book on the theory that it’s felony theft of government property. And also the statute of limitations doesn’t apply because he spent too many days out of state several years ago.

Devil His Due

It’s understandable that for much of the country, the desire to see Trump face justice for his misdeeds overrides any concern about the legal particulars. There aren’t many people who don’t have a strong opinion about Donald Trump at this point, and prosecuting him polls better than not prosecuting him.

But for both principled and more pragmatic reasons, bringing a frivolous and weak case against Trump does nothing to help.

The main argument raised against prosecuting a former president (or potentially an incumbent president) is that it will set off a cascade of tit-for-tat politically motivated prosecutions. This concern isn’t entirely unreasonable. It can be overcome only by arguing the severity of the crime outweighs that interest.

When somebody tried to overturn the Constitution and usurp the highest office in the land, that bar might be met. Having your sleazy lawyer pay off your ex-mistress does not.

In A Man for All Seasons, a fictionalized Sir Thomas More famously rebukes an argument for denying unsympathetic people their full legal rights, for bending the law because they just really deserve it. As he concluded, “Yes, I'd give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety's sake!”

Giving the devil the benefit of law isn’t about protecting the devil. It’s about protecting ourselves. Upholding the rule of law by holding Trump accountable should not be done by undermining the rule of law as it regards the state’s ultimate power to impose criminal punishments. To the degree there’s a moral and constitutional point to be made about how no man is above the law, a bogus prosecution based on the Stormy Daniels affair would defeat the whole purpose.

Sign up for the Beast Digest, a twice-daily run down on each day’s top stories. Don’t miss out, sign up here.