Charles Dicken's The Old Curiosity Shop inspired the cruelest and most famous of Oscar Wilde's upside-down witticisms: "One must have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without laughing."*

The jibe is devastating, but also strangely off-key. The death of Little Nell may be the most famous of Victorian death scenes, but it is hardly the most maudlin. (That honor must surely go to the death of Beth in Louisa May Alcott's Little Women.) The death scene gets much of its power from some very unsentimental elements, not least that the narrator of the death, Nell's grandfather, helped to hasten it by his own errant behavior - and yet still at the end will not confront his own responsibility. Indeed, he cannot even acknowledge aloud the fact of her death. The jibe is off-key too because Wilde himself was hardly immune to the sentimental and even the mawkish. After all, The Selfish Giant is one of the most cloying works in literature.

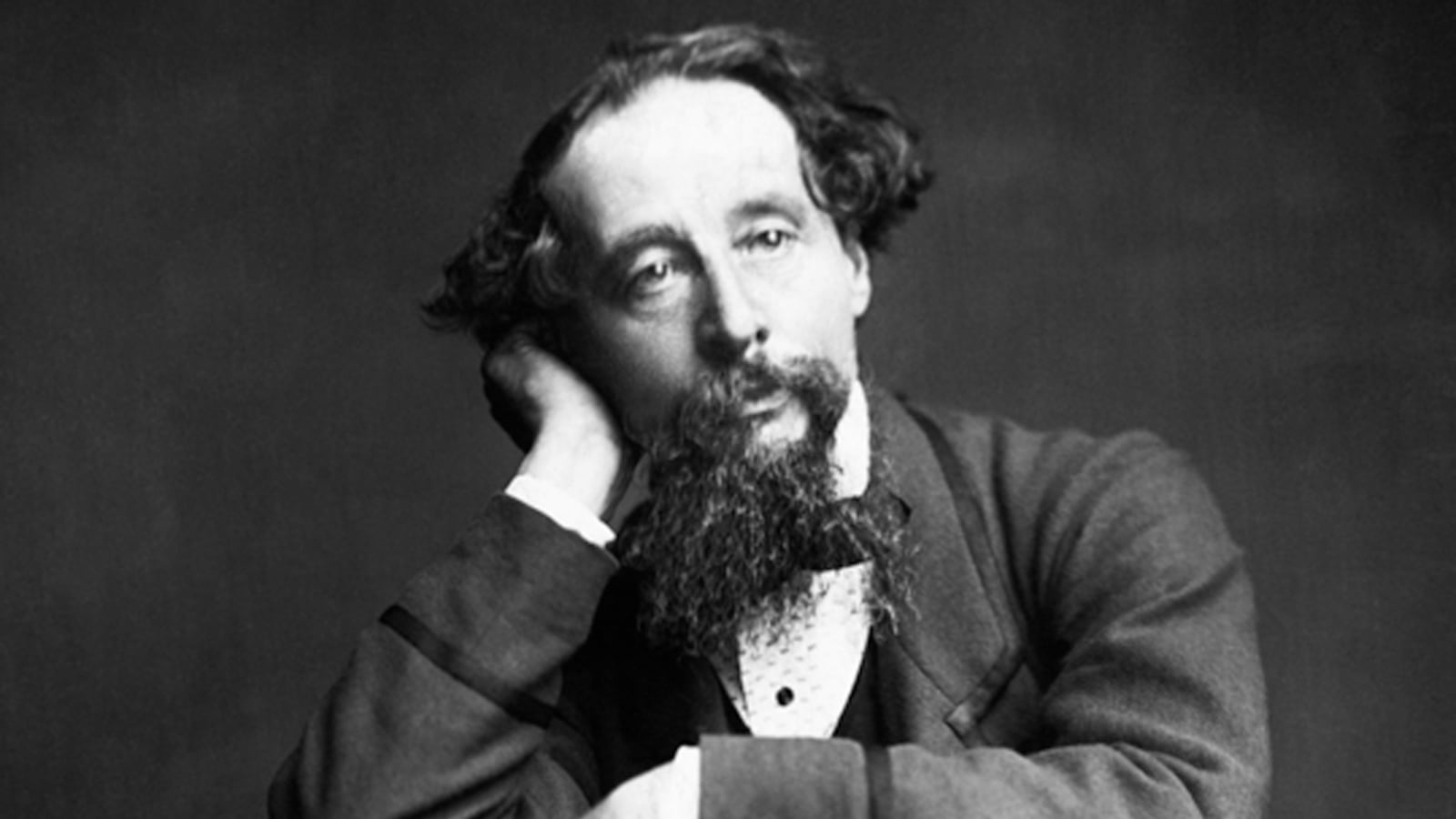

The great theme of The Old Curiosity Shop is early death. As Dickens' biographers explain, the book was written over the year 1840, three years after the death of 17-year-old Mary Hogarth, the younger sister of Dickens' wife. Dickens - then only 25 himself - had developed an intense devotion to Mary. (Although Dickens would later be flagrantly unfaithful to his wife, none of the biographies I've read suggests that Mary and Dickens consummated a love affair.) Mary's loss devastated Dickens. Characters based upon Mary Hogarth show up in many of Dickens' early novels. His actual wife - who bore him a dozen children - seems to have made no impression on his art at all.

Dickens being Dickens, the death of Mary Hogarth did not drive him to record only one girl's fate. It open his eyes to the all-pervading fact of early death in industrializing Britain. Here's from Chapter 45: Nell and her grandfather have been wandering for some time, poor and hungry, ruined by the grandfather's gambling mania. Nell is finally reduced to begging.

She approached one of the wretched hovels by the way-side, and knocked with her hand upon the door.

'What would you have here?' said a gaunt man, opening it.

'Charity. A morsel of bread.'

'Do you see that?' returned the man hoarsely, pointing to a kind of bundle on the ground. 'That's a dead child. I and five hundred other men were thrown out of work, three months ago. That is my third dead child, and last. Do you think I have charity to bestow, or a morsel of bread to spare?'

Oscar Wilde, it should be noted, had also been touched by early loss: his sister, Isola, died at age nine of meningitis. Wilde wrote a (not very good) poem in her memory in the jingling high Victorian manner.

Tread lightly, she is nearUnder the snow,Speak gently, she can hearThe daisies grow

All her bright golden hairTarnished with rust,She that was young and fairFallen to dust.

For Dickens, though, the deaths in The Old Curiosity Shop are more than occasions for grief. They are occasions for outrage. After Nell meets refusal from the unemployed worker who has lost three children, she knocks at another door, and there views this scene:

It seemed that a couple of poor families lived in this hovel, for two women, each among children of her own, occupied different portions of the room. In the centre, stood a grave gentleman in black who appeared to have just entered, and who held by the arm a boy.

'Here, woman,' he said, 'here's your deaf and dumb son. You may thank me for restoring him to you. He was brought before me, this morning, charged with theft; and with any other boy it would have gone hard, I assure you. But, as I had compassion on his infirmities, and thought he might have learnt no better, I have managed to bring him back to you. Take more care of him for the future.'

'And won't you give me back MY son!' said the other woman, hastily rising and confronting him. 'Won't you give me back MY son, Sir, who was transported for the same offence!'

'Was he deaf and dumb, woman?' asked the gentleman sternly.

'Was he not, Sir?'

'You know he was not.'

'He was,' cried the woman. 'He was deaf, dumb, and blind, to all that was good and right, from his cradle. Her boy may have learnt no better! where did mine learn better? where could he? who was there to teach him better, or where was it to be learnt?'

'Peace, woman,' said the gentleman, 'your boy was in possession of all his senses.'

'He was,' cried the mother; 'and he was the more easy to be led astray because he had them. If you save this boy because he may not know right from wrong, why did you not save mine who was never taught the difference? You gentlemen have as good a right to punish her boy, that God has kept in ignorance of sound and speech, as you have to punish mine, that you kept in ignorance yourselves. How many of the girls and boys—ah, men and women too—that are brought before you and you don't pity, are deaf and dumb in their minds, and go wrong in that state, and are punished in that state, body and soul, while you gentlemen are quarrelling among yourselves whether they ought to learn this or that?—Be a just man, Sir, and give me back my son.'

'You are desperate,' said the gentleman, taking out his snuff-box, 'and I am sorry for you.'

'I AM desperate,' returned the woman, 'and you have made me so. Give me back my son, to work for these helpless children. Be a just man, Sir, and, as you have had mercy upon this boy, give me back my son!'

Powering the The Old Curiosity Shop is an idea, an audacious idea for 1840, that much of the suffering Dickens records is preventable and unnecessary. The death of children seemed to Dickens not an inexplicable decision of divinity, but a wrong and waste caused by human action and inaction. As Dickens, the most influential artist of his age, propounded that idea, his contemporaries were acting on it.

Infant and child mortality in Britain began a steady decline some time after 1850, accelerating after 1870, and then accelerating rapidly after 1900. Improvements in diet helped, then improvements in public hygiene, then improvements in the practice of medicine.

Improvements in early mortality transformed public expectations about life and health in Britain.

Dickens, born in 1812, grew up in a world where human health remained more or less what it had been in medieval times - and probably worse than in Neolithic times. Wilde, born in 1868, grew up in a world where health expectations were rising and transforming for the first time in human history.

And yet even now, after so much progress, it remains true that we all die, and some of us die young. Loss and grief and mourning define the human condition. And here too, Charles Dickens has something to offer in The Old Curiosity Shop that remains wisdom and a kind of comfort even to modern readers.

From the start of the book, Nell feels an attraction to churchyards. Tired from her forced journeying, she chooses them as places of rest. Almost the first time she pauses, she is drawn into this scene:

She was looking at a humble stone which told of a young man who had died at twenty-three years old, fifty-five years ago, when she heard a faltering step approaching, and looking round saw a feeble woman bent with the weight of years, who tottered to the foot of that same grave and asked her to read the writing on the stone. The old woman thanked her when she had done, saying that she had had the words by heart for many a long, long year, but could not see them now.

'Were you his mother?' said the child.

'I was his wife, my dear.'

She the wife of a young man of three-and-twenty! Ah, true! It was fifty-five years ago.

'You wonder to hear me say that,' remarked the old woman, shaking her head. 'You're not the first. Older folk than you have wondered at the same thing before now. Yes, I was his wife. Death doesn't change us more than life, my dear.'

'Do you come here often?' asked the child.

'I sit here very often in the summer time,' she answered, 'I used to come here once to cry and mourn, but that was a weary while ago, bless God!'

'I pluck the daisies as they grow, and take them home,' said the old woman after a short silence. 'I like no flowers so well as these, and haven't for five-and-fifty years. It's a long time, and I'm getting very old.'

Then growing garrulous upon a theme which was new to one listener though it were but a child, she told her how she had wept and moaned and prayed to die herself, when this happened; and how when she first came to that place, a young creature strong in love and grief, she had hoped that her heart was breaking as it seemed to be. But that time passed by, and although she continued to be sad when she came there, still she could bear to come, and so went on until it was pain no longer, but a solemn pleasure, and a duty she had learned to like. And now that five-and-fifty years were gone, she spoke of the dead man as if he had been her son or grandson, with a kind of pity for his youth, growing out of her own old age, and an exalting of his strength and manly beauty as compared with her own weakness and decay; and yet she spoke about him as her husband too, and thinking of herself in connexion with him, as she used to be and not as she was now, talked of their meeting in another world, as if he were dead but yesterday, and she, separated from her former self, were thinking of the happiness of that comely girl who seemed to have died with him.

The Old Curiosity Shop is not one of Dickens' most admired novels. Its plot is a compilation of incidents, its main villain is too melodramatically villainous, its construction is so slapdash that Dickens started in the first person and then switched to the third without ever returning to rewrite the opening chapters. "And now that I have carried this history so far in my own character and introduced these personages to the reader, I shall for the convenience of the narrative detach myself from its further course, and leave those who have prominent and necessary parts in it to speak and act for themselves."

Yet that scene of the old woman waiting across time for her departed young husband will haunt the memory of anyone who has lost a loved one too soon - and explains why, despite the excesses scorned by 20th century modernists, Dickens still lives as an artist even after so many of his more tasteful detractors have faded away.

* The quip is reported in many slight variations, but you get the idea.