The first time Marcus Samuelsson ate a bowl of gumbo, he was sitting at a table inside New Orleans’ famed Dooky Chase’s Restaurant. Next to him was legendary chef Leah Chase, who helmed the restaurant from 1946, when she and her husband Edgar “Dooky” Chase II took it over, until her death in 2019.

Samuelsson, the acclaimed Swedish-Ethiopian chef behind New York’s Red Rooster and Ginny’s Supper Club, among others, emigrated to the U.S. in the early 1990s. Early on, Chase became one of his mentors. Her decades of experience both as a chef and a leader in her community, which earned her the unequivocal moniker as the Queen of Creole Cuisine and recognition as a civil rights icon, proved invaluable to Samuelsson.

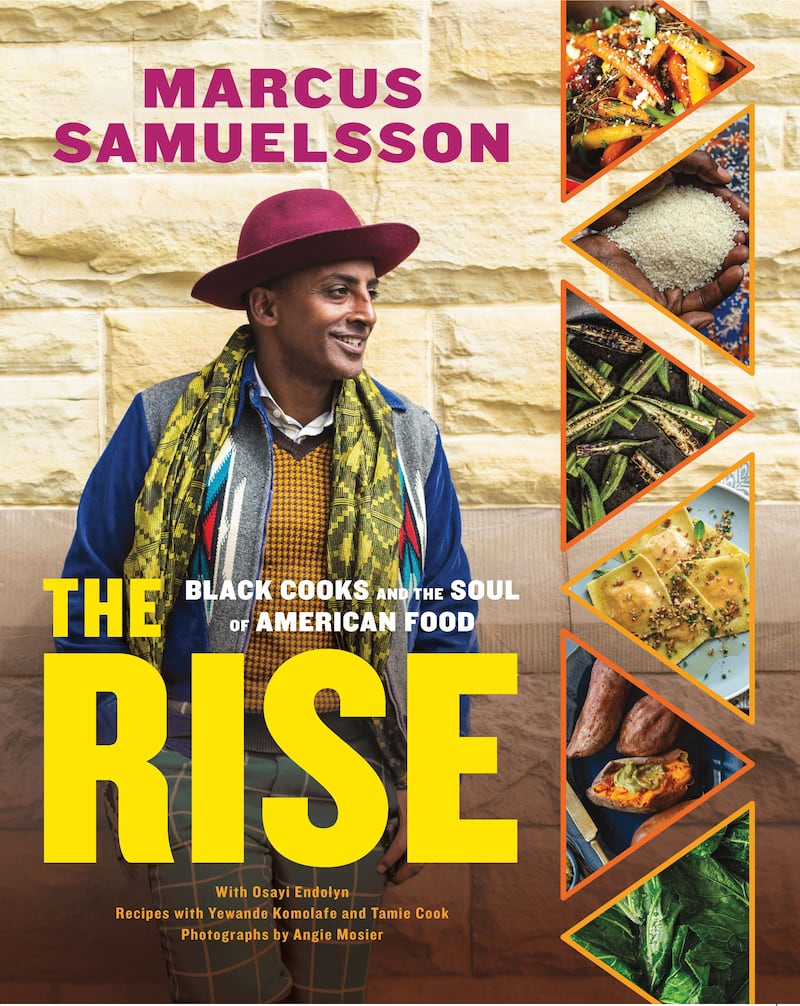

“She came to my restaurant often and guided me,” says the chef, whose latest cookbook, The Rise: Black Cooks and the Soul of American Food, celebrates the contributions of Black chefs, including Chase, to American food culture. “She talked about how it was to be a Black lady opening Dooky Chase in [1946] when Black and white people couldn’t eat together. She’s seen the Civil Rights movement, she’s seen Hurricane Katrina, she’s seen everything.”

Through it all, Chase was serving Creole comfort food, including gumbo—a dish that, Samuelsson asserts, is as iconic in American food culture as mac and cheese or fried chicken. One bite of her okra-and-shrimp stew is all it takes to transport him back to Chase’s dining room in New Orleans’ Tremé neighborhood.

“Eating her gumbo, going to Dooky Chase many times, cooking at Dooky Chase—her voice is clear to me still to this day,” he says. “I don’t know if there’s a dish that represents a city better than gumbo. When you taste the sausage against the okra against the seafood, you taste New Orleans.”

Though he didn’t grow up eating gumbo, Samuelsson says that the dish offers a special kind of comfort nonetheless, beyond being a fantastic antidote to cold weather. When he considers what comfort food has meant throughout his life, he looks to three different places: the Ethiopian food his wife makes, the Swedish meatballs and fish dishes he grew up with, and the “comfort food of Harlem that has that migration, Southern narrative.”

“Being an American and being an immigrant, the fact that we can express ourselves through food—food is identity, right?” he says. “When you come as an immigrant or you’re a person of color, the past is very nonlinear because we had to make do with very simple ingredients. Sometimes we move to a place where comfort food changes. In The Rise I really explain that Black food in this country is not monolithic. There’s many different entry points to it.”

While gumbo’s exact origins are unknown, its ingredients are representative of the city’s history and diversity. That includes the okra brought to North America by enslaved Africans, the traditional French andouille sausage, and the ground sassafras leaves found in Choctaw cuisine.

“When you understand gumbo, you also understand America and New Orleans,” says Samuelsson. “There are French techniques, there are African techniques, there’s Haitian and Spanish influence in it. That’s why Creole cooking is so unique.”

This winter try Samuelsson’s tribute to Dooky Chase’s iconic gumbo at home and enjoy a comforting taste of New Orleans’ rich and vibrant culture.

While some gumbo recipes are made from a roux base, Samuelsson’s forgoes the flour altogether, starting instead with the holy trinity of Creole cuisine: onion, celery and bell peppers. A recipe for shrimp and grits with gumbo sauce in honor of Red Rooster executive chef Ed Brumfield, whose father is a Louisiana native, is also featured in The Rise. It starts off with this same technique.

“His Papa Ed’s Gumbo is a legend at Red Rooster,” says Samuelsson. “It’s that idea of using the trinity—onion, peppers, and celery—and then adding in sausage and seafood and okra, and building this layer stew that is so delicious.”

From there, you’ll add in flavorful and fatty chorizo, which will render its fat to enrich and provide texture to the base of the stew. The liquid ingredients—fish and chicken stocks, apple cider vinegar and crushed tomatoes—will cook down and thicken with a little help from the dish’s two star ingredients...

Gumbo is often divided into two camps: okra gumbo or filé gumbo, depending on the thickening agent used. Samuelsson, however, uses both. “We wanted to show exactly those two different points,” he says.

The first known appearance of the dish is on a menu for a gubernatorial reception in New Orleans in 1803, according to the Southern Foodways Alliance. Various iterations of the dish are then featured in recipe books published later in the 19th century, some using okra and others not. There is reason to believe, though, that it was a key player from the beginning, as the word “gumbo” is likely derived from ki ngombo, a West African Bantu term for okra.

“When you do a book that highlights the African American journey when it comes to food, [okra] is a very important ingredient and subject,” says Samuelsson. Diced into his gumbo, okra lends a unique vegetal flavor and its mucilaginous qualities act similarly to cornstarch, thickening the liquids in the dish and adding another dimension of texture.

Filé powder, which is made from the ground leaves of the sassafras tree and has roots in Native American cooking—particularly within the Choctaw tribe—also acts as a thickener and, Samuelsson says, is reminiscent of a flavorful bay leaf ground up and blended with Old Bay seasoning. He adds, “it’s very unique and is something you don’t find often outside gumbo.”

In addition to the filé powder, Samuelsson’s gumbo calls on a couple of other spices to round out its vibrant, warming flavor. Alongside salt and pepper, of course, you’ll also add cayenne powder and smoked paprika. If you’re not accustomed to spicy foods, however, you don’t need to worry. “Gumbo is flavorful without being spicy,” he says. “Which means that, no matter how your [dining] party responds to heat, everyone can enjoy it.”

Each element in Samuelsson’s gumbo recipe contributes some unique flavor or texture to the dish, and its proteins are no exception. Chorizo, the heavily seasoned pork sausage that originated in Portugal and Spain and is also a staple in Mexican cuisine, goes in first so its fat has a chance to render. He then incorporates French andouille, a coarser but also heavily seasoned sausage, and shrimp, a staple element in many a gumbo recipe.

“You want a sausage with flavor because making a gumbo comes down to the best flavor combination,” says Samuelsson. “Using sausages like chorizo and andouille gives you that. It has garlic, it has chilies—all of those things—and it has natural fats.”

The andouille and shrimp are added at the very end to avoid overcooking them. “You’re building up the stew,” he says. “The things that are the most delicate you’re adding last.”

In The Rise Samuelsson suggests you serve the gumbo over rice, but he’s also a fan of it over a bed of grits—it’s served both ways at Red Rooster.

“Sometimes the word gumbo can be more intimidating than what it is. It’s a great, flavorful seafood stew that you should do coming into the holiday season,” he says. “Gumbo will be appreciated.”

INGREDIENTS

- 3 Tbsp Vegetable oil

- .5 cup Celery, diced

- .5 cup Red onion, diced

- .5 cup Red peppers, diced

- 4 Cloves garlic, minced

- 1 tsp Kosher salt

- .5 tsp Freshly ground black pepper

- 4 oz Ground chorizo

- 1 (14-oz) Can crushed tomatoes

- 12 oz Fresh okra, diced small

- 1 Tbsp Smoked paprika

- 1 Tbsp Filé powder

- 1 tsp Cayenne pepper

- 2 cups Fish stock

- 2 cups Chicken stock

- 2 Tbsp Apple cider vinegar

- 1 pound Large shrimp, peeled and deveined

- 8 oz Smoked andouille sausage, in quarter-inch thick slices

- 6 cups Cooked rice, for serving

- Scallions, chopped

- Fresh parsley, chopped

DIRECTIONS

- Heat the vegetable oil in a large saucepan or Dutch oven set over medium-high heat. When the oil shimmers, add the celery, onion, peppers, garlic, salt, and pepper and cook, stirring frequently, until the onion is translucent, 3 to 4 minutes.

- Add the chorizo and cook for 4 to 5 minutes, stirring frequently.

- Add the tomatoes, okra, paprika, filé powder and cayenne and continue cooking for 4 to 5 minutes, stirring frequently.

- Add the stocks and vinegar and bring to a simmer.

- Decrease the heat to low, cover, and cook for 20 to 25 minutes, stirring occasionally. The filé powder, which is made by grinding sassafras leaves, will thicken the stew.

- Add the shrimp and andouille and stir to combine. Continue to cook for 4 to 5 minutes, until the shrimp are just cooked through. Serve the gumbo over rice, topped with scallions and parsley.

Excerpted from THE RISE by Marcus Samuelsson with Osayi Endolyn. Recipes with Yewande Komolafe and Tamie Cook. Copyright © 2020 by Marcus Samuelsson. Photographs by Angie Mosier. Used with permission of Voracious, an imprint of Little, Brown and Company. New York, NY. All rights reserved.