Chief Justice John Roberts issued his 2023 year-end report for a year in which the U.S. Supreme Court suffered a historic loss in credibility caused by reveals of undisclosed benefits given to the justices—in the case of Justice Clarence Thomas, the value likely in the millions—and the thoughtless glee with which the newly empowered conservative majority overturned precedents to further a Federalist Society agenda.

Adding to the damage done to the court was Justice Samuel Alito, feeling so empowered that he took to writing opinion pieces in The Wall Street Journal asserting that Congress has no power to regulate the high court’s ethics, as well criticizing ProPublica for its investigations into Alito being flown to a luxury fishing trip by a billionaire with matters before the court.

One might have expected the chief justice to at least offer some assurances about the court’s ethics to the public. For example, he could have highlighted the fact that they finally adopted a code of judicial ethics, albeit a toothless one.

But Roberts didn’t do that. Instead, he focused on… wait for it… the role of artificial intelligence in the law.

The chief justice’s AI report reads like it was written by ChatGPT in response to a request for something like “write something boring about the federal judiciary that does not mention ethics scandals.” Actually, Roberts barely discusses AI in the report’s seven pages—in addition to six pages worth of appendices illustrating just how few cases SCOTUS actually has to work on.

He spends the first five pages giving a grade school-like report of how the courts have evolved from using quill pens, to typewriters, and now computers. Nothing quite says “we live in a museum” like including museum photos of “quills and inkwells like those used by Justices in the 19th century”—yes that is an actual caption to a photo in his report—and photos of the late Justice Byron White using a typewriter and the late Justice Sandra Day O’Connor using a computer, the latter image perhaps meant to invoke how progressive SCOTUS has been. (Gosh, look at that! The first woman justice leading the technological charge by using a computer!)

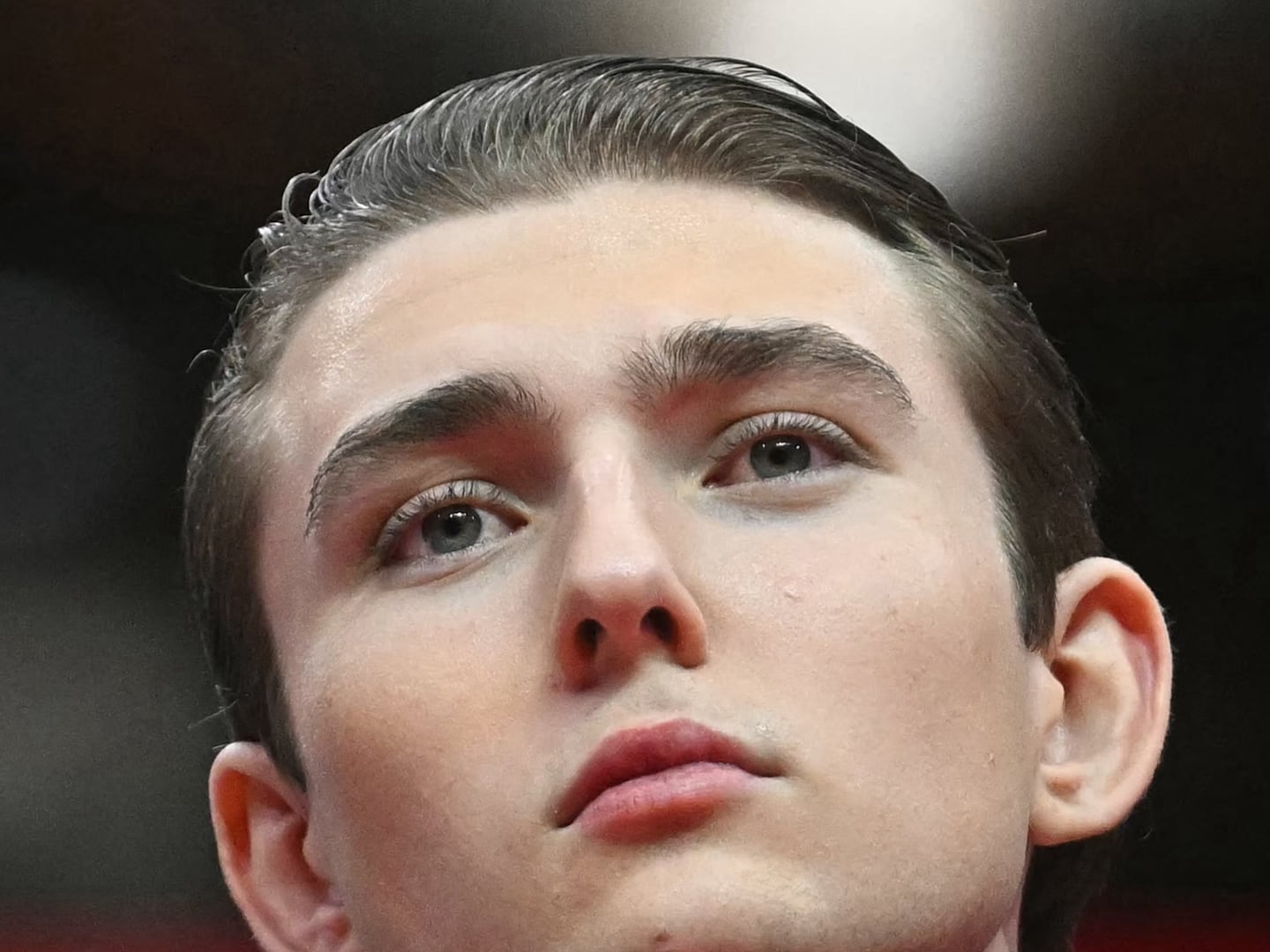

Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts attends the State of the Union address on Feb. 7, 2023.

Jacquelyn Martin-Pool/Getty ImagesWhen Roberts does get around to discussing AI for barely two pages, his insights are so bland that Above the Law said about it: “If AI had a sense of shame, ChatGPT would be embarrassed by this level of superficiality.”

And it is an embarrassingly airheaded take on technology for a jurist who is supposedly interested in the intersection of technology and law, and who wrote the opinion requiring law enforcement to get warrants for cellphone searches.

Roberts does display a kind of “dad-joke” delight in using terms like “hallucination”—the current jargon for when AI makes up stuff like it did in the much-publicized cases of lawyers using AI-produced citations of non-existent legal cases.

The lawyer representing former Trump fixer Michael Cohen apparently did that after his client gave him some AI research, and he submitted it without bothering to cite-check the cases. Chief Justice Roberts adds what is probably meant as a humorous parenthesis to this careless and sanctionable action by the lawyers saying: “(Always a bad idea.)” But it just comes across as patronizing, as does his observation that law professors are supposedly suffering “awe and angst that AI apparently can earn Bs on law school assignments”—as though to imply that AI can be helpful with lesser non-A student intellects.

He ducks any real discussion of the true legal ethics issues that AI implicates, such as how the use of it may affect client confidentiality and what kind of disclosure duties do lawyers have to their clients when they use AI.

But taken up as he is with his zeal to produce a report that avoids the ethics scandals threatening his court’s credibility, Roberts unwittingly guts one of his own core assertions about how judges are just umpires whose role it is to “call balls and strikes, and not to pitch or bat.” Roberts famously said this in his confirmation hearings, and it symbolizes his supposed push-back against any partisanship or ideology in his rulings.

Supreme Court Associate Justice Clarence Thomas and Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts.

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesBut now as he searches for ways to show off his understanding of the limitations of AI, he says that in professional tennis line judges have been replaced by optical technology to call balls in or out—which he asserts is inapplicable to judging. That’s because “legal determinations often involve gray areas that still require application of human judgment.”

So much for the umpire analogy.

AI does require our attention as it raises a myriad of legal issues including racially biased facial recognition that ruins lives, and pushing the boundaries of copyright protection—as highlighted in the recent lawsuit by The New York Times against OpenAI and Microsoft over allegedly unauthorized use of published work to train AI.

As with all technology, it possesses the potential to increase transparency and access through greater communication speed and reach. However, that promise—as well as the dangers of potential abuse—require us to study and think about it without a political or social agenda. In that regard, John Roberts is poorly equipped to lead the way.

It is fitting that the chief justice opens his report with a story about how a century ago, FDR’s New Deal sought to bring electricity to homes in rural America. In Roberts’ words, “Then came teams of men to clear the brush, sink the poles and wire homes to the still inert grid.”

This is the sort of “American technological progress built by white men” mythology that conservatives love to promote.

He cites the writer Robert Caro, who wrote that in some areas the projects took so long that families forgot the work was still going on, and recounts an excerpt by Caro in which a family comes home to find their home finally lit up. The mother is afraid that the house is on fire, but the daughter reassures her it’s not a fire: “No, Mama,” the daughter said. “The lights are on.”

Roberts misses the irony here. For the high court’s house is on fire. And the lights are on, but nobody is home.