HONG KONG—Earlier this week, Beijing’s State Council Information Office—a Chinese Communist Party propaganda arm that is part of the country’s highest administrative body—released a perplexing report. Titled “Human Rights Record of the United States in 2017,” it devotes some 6,000 words to a chronicle of abuses that took place in America last year.

The paper apparently was shared online in response to the U.S. State Department’s annual report on human rights conditions in the People’s Republic, which calls out some of the worst violations committed in the name of stable governance in China, including arbitrary executions, government-directed abductions both within and beyond the country’s borders, forced confessions that are often televised or shared via state media, and more. The State Department lists the Chinese Communist Party alongside the governments of Russia, Iran, and North Korea as “forces of instability” because of their domestic human rights abuses.

The State Council’s researchers tick off calamitous events plucked from the headlines, such as the October 1 shooting in Las Vegas, where 58 concert-goers lost their lives, as well as violence that is rooted in racial tensions. They also pull quotes from research on the wealth gap, refer to the Trump administration’s “Muslim ban,” and—here’s a strange one—mention the vandalizing of LeBron James’s home with racist graffiti.

Beijing’s report gets one thing right: these instances all reflect social ills in the United States. But what the report’s authors conveniently leave out is that there are many actors Stateside who endeavor to cure these symptoms without facing harassment or persecution from their government, as they would in China.

The report was published in both English and Chinese, and shared via state media outlet Xinhua. Its English version is presumably produced for foreign readers who have regular access to other news sources that actually report Chinese crackdowns on lawyers, activists, the LGBT community, and anyone who deviates even slightly and publicly from the Party line.

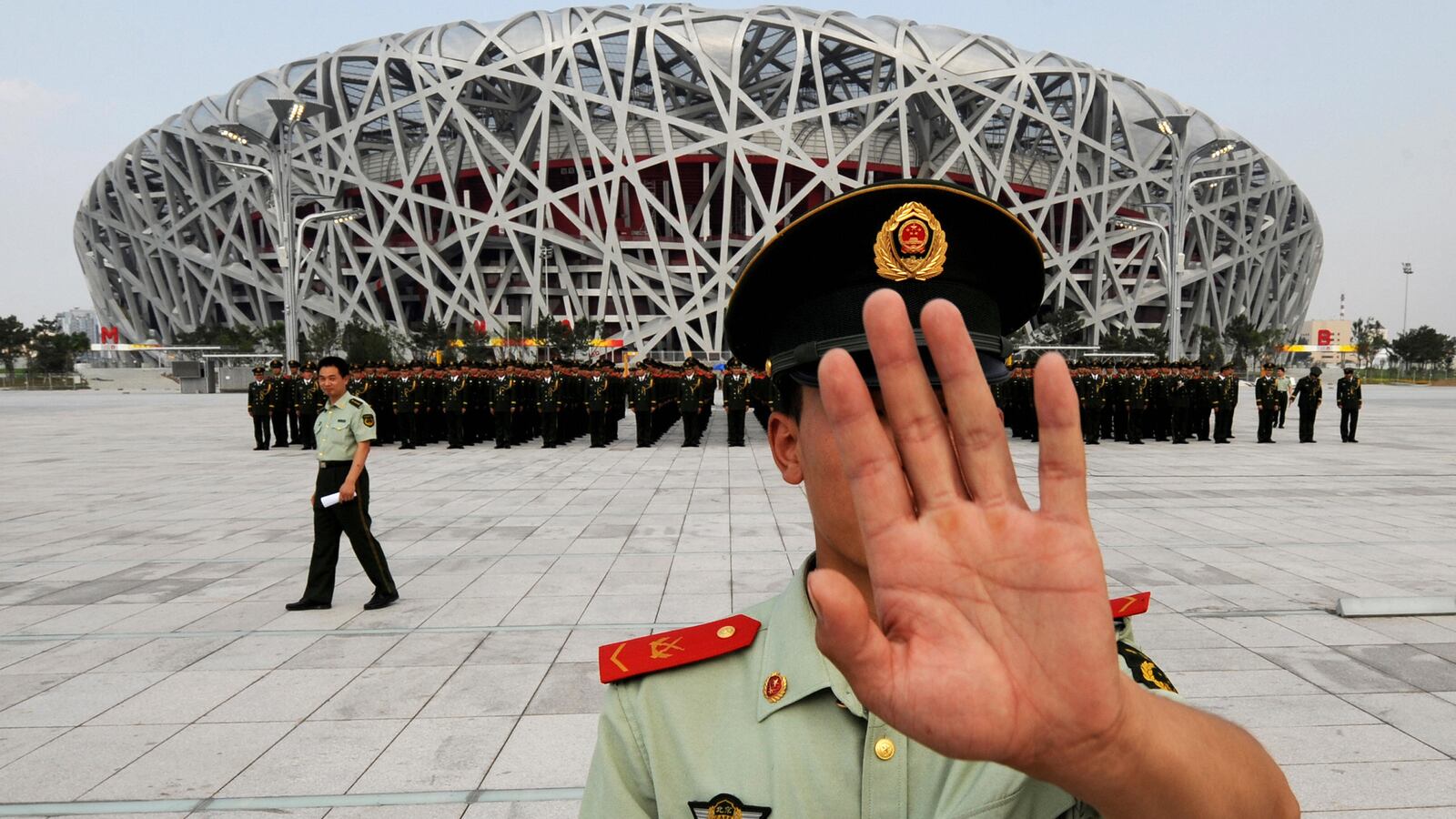

With Chinese president Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power, there have also been significant changes in how the Party communicates its message, as if preparing to move from crude propaganda to more sophisticated information war.

In the past, Chinese diplomats and government spokespersons would step onto the podium to reject criticism from other nations, of course, but now propaganda officers and state media have ramped up production of materials that are meant to be disseminated as white papers and news reports.

The CCP is expending incredible amounts of time, money, and effort to sculpt its image abroad. A $6.6 billion venture will merge existing Chinese media bodies to create the State-Council-overseen propaganda monolith Voice of China—an organization whose name was unsubtly lifted from Voice of America. The Communist Party also has established cells at educational institutions all over America for “ideological guidance.” In some cases, like the report issued by SCIO, resources are channeled to damage the reputations of other nations, but with little effect.

This recalibration of how Beijing approaches media is still in its nascent stage, and the Party’s propaganda machine is eons away from cracking the code of global communication. What the CCP and Xi have not realized is that riffed-off ideas like the Voice of China and the “Chinese dream” have no pull among international audiences, especially in developed nations. Few doubt China’s technological and economic might, but the Chinese government’s tone-deaf self-praise discredits much of its rhetoric.

In December 2017, SCIO published a white paper claiming that the “undertaking of human rights protection in China has made much headway.” This was mere months after Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo died while serving an 11-year prison sentence for “inciting subversion;” his widow remains under police surveillance.

Women’s rights activists in Guangzhou were expelled from the city in May after they spoke out about sexual harassment on public transportation. At least 120,000 Uyghurs are currently held in Maoist-style re-education camps. Huang Qi, one of the founders of a website that tracks and documents public protests in China, was detained for eight months facing the charge of “illegally providing state secrets to foreign entities” before he was allowed to meet with legal counsel; 10 of his colleagues were jailed in 2017. The list goes on, and these are only a few examples from last year of human rights abuses by the Party.

During the National People’s Congress in Beijing last month, Xi vowed that the Party would “take [its] due place in the world,” a stark contrast to the talk of openness and international cooperation previously touted by the national leader as an alternative to a global order led by Trump’s United States.

But the latest round of digs at what the Chinese see as blemishes on America’s human rights record was a botched attempt to elevate China’s position on the world stage, and it revealed a faint understanding of how the rest of the world consumes information.

With crippling biases and constant censorship, the Party’s hopes to draw a larger and loving audience are severely misplaced. All the rest of the world sees is an onslaught of propaganda extolling the myth of an imagined greatness, with words and images forming a security blanket for the Party itself.

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated incorrectly that the report in question had not been published in Chinese.