HONG KONG—In the Chinese Communist Party’s collective headspace, open dissent in Hong Kong is a problem to be solved. The city of 7.5 million people has been a thorn in the party’s side for many years and CCP chairman Xi Jinping wants to change that while he is still in command of China’s government.

On Thursday evening, the party said it will “improve” the way Hong Kong is governed—not by addressing the demands of the city’s denizens, but by implementing a vague security law that would bypass the local legislature’s law-making process, thus rendering moot Hong Kong’s status as an autonomous region.

Unlike mainland China, where the CCP has erected barriers on the internet that are called, inevitably, the Great Firewall, Hong Kong provides freedom of speech and expression, including in cyberspace—at least for now. But China’s pledge to “improve” Hong Kong’s governance, paired with its hallmark vagueness in the proposed security bill’s legal language, has people in the city concerned that this may soon be a thing of the past.

This goes beyond worries about banning criticisms of China’s central authorities. The larger, deeper fear is that Beijing is chipping away at the freedoms that are present in Hong Kong—of the press, of assembly, of association, of religion, and to maintain privacy of communication. These are the questions that Hongkongers now grapple with, in much more real terms than ever before: What can you do when the law isn’t written to protect you? And when will their home, for now still an international hub, become “just another Chinese city”?

Hong Kong became a global financial center when it was a British colony, where, even now, capital flows freely and the city maintains its own currency that is pegged to the U.S. dollar. When China began economic reforms in the late 1970s, after Mao Zedong’s death, it relied on Hong Kong’s existing ties with the rest of the world to establish new connections. And after sovereignty over Hong Kong was passed from the United Kingdom to China in 1997, the city maintained a level of democratization that is unseen and seemingly unimaginable in the mainland.

News about the announcement in Beijing broke on Thursday with a leak reported by local Hong Kong news outlet HK01. There were immediate reactions. Users of an online forum called LIHKG for people discussing current anti-government movements prompted each other to install VPNs (Virtual Private Networks) in case the Great Firewall is activated in Hong Kong. They are wary of a larger push by authorities to adopt China-style internet surveillance. Since Thursday afternoon, buyers’ guides to VPNs have been circulating on Telegram and Facebook.

When Beijing’s proposal is ratified, as seems certain, Chinese national security agencies will have the power to move beyond covert and influence operations to establish a formal presence in Hong Kong—including the division that monitors online media, content, and communications.

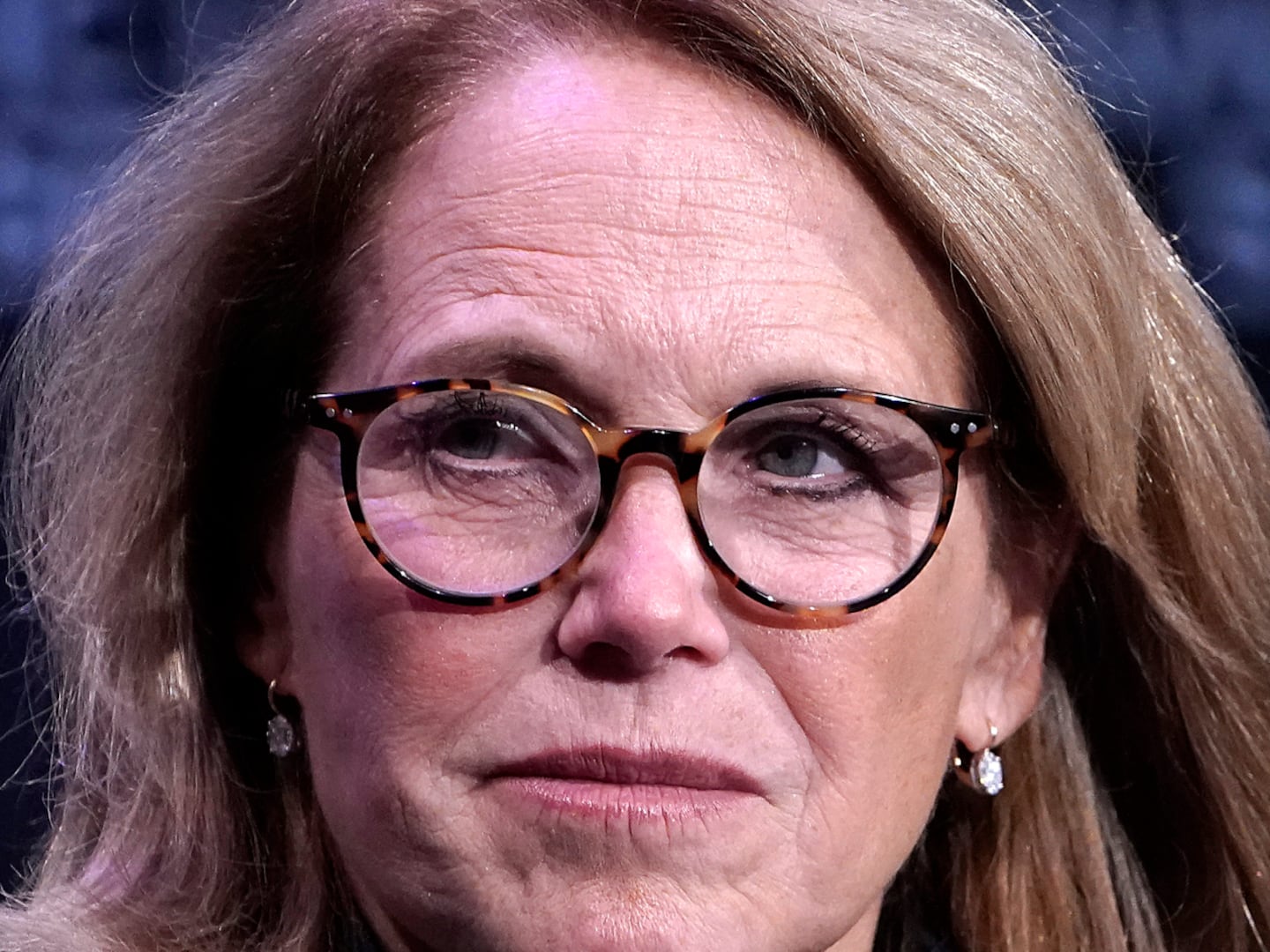

Speaking at a press conference on Friday, a Hong Kong Democratic Party lawmaker, Helena Wong, said, “even the [Hong Kong] government will not be able to regulate what the agents do” in the city.

Chinese authorities utilize automation and a fleet of human censors to monitor posts on social media, news reports, content on video streaming platforms, films, TV shows, printed matter, and personal conversations in messaging apps—all to control the flow of information and, more importantly, its tone.

Certain topics, like the Tiananmen Massacre or overt criticisms of the CCP, often are blocked automatically and immediately. Other subject matter—like LGBTQ rights or the coronavirus outbreak that likely originated in Wuhan—are massaged, reshaped, and then restricted based on directives from the party.

Even so, dissent and disapproval manage to thrive where there are cracks in the CCP’s systems of constriction. Algorithms often can’t process satire, and codewords can convey discontent.

The leaders in Beijing see incorporation of Hong Kong as just another city—and one inside the Great Firewall— as the ultimate objective. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang said on Friday morning that the CCP will ensure that the government of Hong Kong will “fulfill its responsibilities,” and that the Chinese authorities will carry out a plan to assimilate Hong Kong into southeast China.

The announcement on Thursday evening brought forth comparisons to rules that were proposed by Hong Kong’s own government in February 2003, when officials introduced a bill that invoked vague definitions of “treason, subversion, secession, and sedition” to give authorities the power to conduct searches and seizures without warrants, as well as shutter any organizations or media outlets that it deemed a threat to the city’s security.

This sparked widespread opposition as well as large-scale demonstrations in Hong Kong, like those that took place last year. In July 2003, 50,000 people surrounded the legislative building. A week after that, the city’s Secretary for Security resigned.

Since then, the people of Hong Kong have organized protest movements in which they express sharp anti-CCP views, targeting the party’s representatives in the local government as well. There was the Umbrella Movement in 2014 that lasted for 79 days, when people occupied major roads in the city. A summer uprising last year, sparked by an extradition bill that Hongkongers believed would provide cover for the CCP’s politically motivated punishments, led to months of anti-government and anti-police actions across the city, Beijing has decided enough is enough.

By framing the most recent anti-government actions in Hong Kong as terrorist acts, and by suggesting that there is the “seed of terror” in the city, Chinese authorities are invoking the power to pass laws related to national security and reshape the governance of Hong Kong. This is at odds with the city’s special status that the U.S. State Department and other American entities often refer to, and which is zealously guarded by Hongkongers.

With this move, what is the Chinese Communist Party truly trying to outlaw in the port city? Beyond its vague scheme to ban “sedition, treason, and secession,” Beijing is giving its figureheads in Hong Kong as well as the city’s police force carte blanche to stamp out dissent—dissent that mobilized millions of people to march through the city in peaceful rallies, galvanized the black bloc’s “Be Water” philosophy of resistance, reshaped Hongkongers’ spending habits, and moved people to vote in what became a landslide victory for pro-democracy candidates in an election last year.

What the CCP wants to extinguish is a city’s refusal to assimilate into a system that offers no choice other than the narrow path set forth by Beijing’s political rulers—the party’s way, or none at all.