HONG KONG—Given its vast territorial ambitions that span global waters from the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean to the Arctic, it really should come as no surprise that the Chinese Communist Party is also aiming upward, far beyond the confines of the Blue Planet.

Five years ago, Chinese President Xi Jinping promised the nation that China will send a taikonaut to the moon by the 2030s. (So far, 11 have flown into space.) As with the other policies that Xi has shaped as his forthcoming legacy, there has been a strict follow-through, with the nation’s aerospace experts improving their craft at dizzying speed.

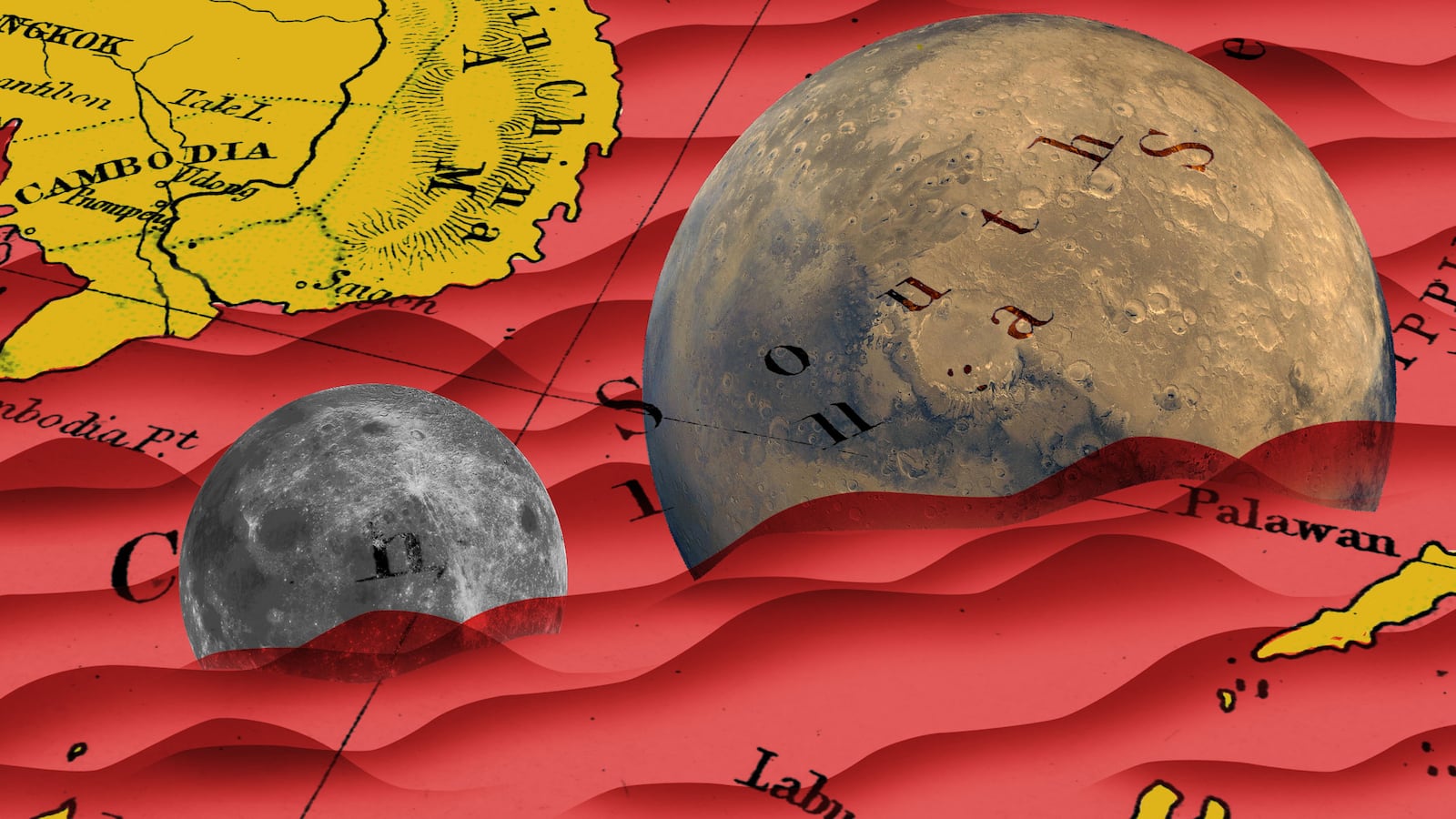

There is one Party official who is extremely outspoken about China’s astral aspirations: Ye Peijian is a 73-year-old aerospace engineer and head of the Chinese lunar exploration program. While fielding scripted questions from a reporter at the CCP’s annual plenary sessions in Beijing last year, he left quite an impression. When asked why China is going to the moon, Ye said, “The universe is an ocean, the moon is the Diaoyu Islands, Mars is Huangyan Island. If we don't go there now even though we’re capable of doing so, then we will be blamed by our descendants. If others go there, then they will take over, and you won’t be able to go even if you want to. This is reason enough.”

Responses like Ye’s are part explainer, part propaganda, all dog whistle. The Diaoyu Islands, as China calls them, are an uninhabited 1,700 acres that are known as Senkaku in Japan, and sovereignty over these small patches of bare rock has been a flashpoint between the two nations for decades. In the same vein, Huangyan refers to Scarborough Shoal, a reef in the South China Sea that is also claimed by Taiwan and the Philippines. By invoking the names of these contested outposts, Ye delivered a crystal-clear message that left no room for misunderstanding among a domestic audience. For Ye and the CCP, going to space isn’t just a matter of scientific achievement or national pride. It’s a move to wrest control of new lands from other nations, and to write the histories of those territories before others can.

Every so often, we see that Donald Trump’s head is in the stars as well. He went off-script recently to talk impromptu about the creation of a “Space Force,” and in his inaugural address he said that the United States will “unlock the mysteries of space” without giving clear direction for NASA. But the CCP already has shaped a consistent space exploration program. In 2015, the Chinese National Space Administration conducted 19 successful launch missions, with 21 to follow in 2016, just one short of the United States.

There have been setbacks for Beijing’s aerospace program. Although there were around 30 launches scheduled for 2017, a failed test of the Long March 5 heavy-lift rocket froze progress for nearly three months. But CNSA seems to be back with a vengeance, aiming to clear that backlog and land a rover on the far side of the moon by the end of 2018. The plan is to reach farther in 2020, and land a rover on Mars—a feat that only the United States has accomplished so far.

Trump’s grandstanding about a Space Force comes months after tough battles were fought to maintain funding for peaceful space exploration and related research in the 2018 fiscal year. But he does seem to see the military potential. The White House has released an America First National Space Strategy, in which the Oval Office has interpreted space as a “warfighting domain.”

The trillion-dollar question is: does Beijing see it the same way?

The Chinese space program is opaque, but it fits with Xi’s policy of “civil military fusion,” which translates cutting-edge technological research into military power and modernization of the People’s Liberation Army, much the way the American military often depends on civilian contractors in the defense industry. This aligns with the plan of “Made in China 2025,” which has been at the heart of U.S.-China trade war discussions, as the CCP attempts to bolster multifarious industries at home and dilute its reliance on other nations. The key consequence will be for the People’s Liberation Army to dominate emerging technologies in China, including those related to maintaining a presence in space.

Chinese political analysts have shared impressions that America has been trying to lure China into a space and arms race, similar to competition with the USSR during the Cold War. Indeed, the People’s Republic is still playing catch-up to the U.S. Yet its achievements already are playing into Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions on our planet. Satellites for a navigation system called Beidou are being carried by China’s frequently launched spacecraft, and are deployed as a homegrown version of America’s global positioning system. More noteworthy is the integration of quantum cryptography into the Micius satellite, meant to test a communication channel that is designed to be much harder to crack than existing means.

So the race is on, not only between the U.S. and China, but also involving India (for Mars), South Korea (for rocketry advancements), and Japan (for the moon). The prize for the CCP isn’t only the sky as Ye Peijian sees it, but also, of course, the oceans and continents where China is projecting its power with land grabs near and far.