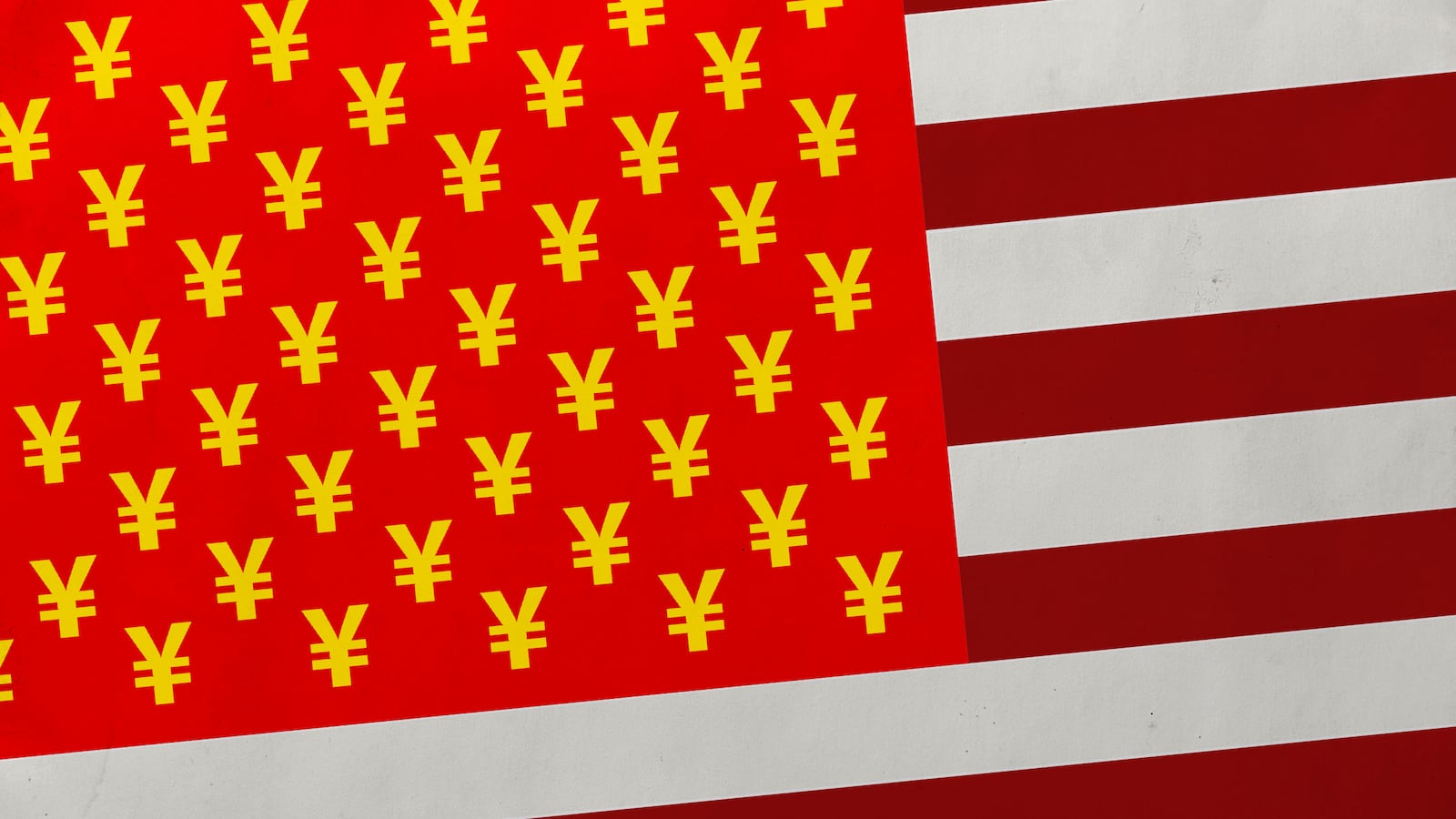

HONG KONG — China is America’s biggest banker — and the rest of the world’s, too. As the financial power of the United States dwindles, and Trump policies inject increasing doses of chaos to its management, China’s carefully calculated chokehold over entire nations, entire economies, is paying off. In front of our eyes, the debt controlled by the People’s Republic of China in client states is being reshaped into tangible geopolitical benefits.

The strategy was based, significantly, on a favorite European colonial strategy of the 19th century, when debts and debt collection was used around the world to gain decisive influence on weaker countries. In China’s case Western forces penetrated its economy and instigated armed conflicts. Chinese rulers ended up with huge war debts. To pay them off, the Chinese courts wrung peasants dry, weakening the nation enough for it to be carved up, temporarily, by colonial powers. In particular, Hong Kong was ceded to Britain as a colony until 1997.

Today, Beijing’s expanding influence as a global creditor can be seen in some striking figures:

As of June last year, 44 percent of Burma’s external debt was owned by China. Laos, which often is characterized as the poorest country in this corner of Asia, has kept the details of its major projects under wraps, but reportedly has received loans of $465 million and $600 million from the Export-Import Bank of China, meant as operation costs for the China-Laos Railway and funds to cover a hydropower project. (China Exim, which issues loans based on the Chinese Communist Party’s policy objectives, never shares data about sums lent to foreign entities.)

Move west, and we find Sri Lanka, which is obligated to pay China $480 million in interest each year. The strain on Colombo has been so great that a 70-percent share of the island nation’s Hambantota Port was handed over to a Chinese state-owned firm on a 99-year lease. Further afoot, more than 70 percent of the Maldives’ external debt is owed to China.

On the African continent, China now owns 70 percent of Kenya’s foreign debt, a tenfold increase in five years. Its neighbor Djibouti has made headlines for hosting the first overseas facility of the People’s Liberation Army; more profound is the fact that China had loaned $1.4 billion to the East African nation as of last year, a figure that represents 75 percent of Djibouti’s GDP.

Most importantly for the United States, the People’s Republic owns 19 percent of all American Treasury Bills, notes, and bonds held by foreign bodies as of May 2018. Donald Trump’s $12 billion soybean subsidy? Squint a little and you’ll see that it is Chinese money . . . borrowed to wage a trade war with the lender.

These figures are just a sample of China’s foreign credit operations.

The United States aside, Beijing offers easy loans to nations eager to modernize their infrastructure, often in places where there is a crucial need for such improvements. It is common for allegations of collusion between local government officials and Chinese entities to arise, but this hasn’t slowed down the dealmaking. Chinese money goes to a new metro in Lahore, a bridge over the Padma River in Bangladesh, airport upgrades in Harare, a new nuclear power plant somewhere in Turkey, and a litany of other projects. For those in the non-aligned “Third World,” it is China’s coffers that seem to offer a potential path to prosperity.

Some chalk up this phenomenon as the result of efficient propaganda around Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, or the establishment of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which is described as a rival to the World Bank.

Instead, the key is that many nations now see China as an alternative to the West. Defense dollars—for instance, the $7.5 billion Asia Pacific Stability Initiative proposed by John McCain for more military infrastructure, additional exercises, and munitions—don’t help America make friends in most places in the world.

The vulnerability created by debt is ripe for Beijing’s picking. Alhough there is truth in China’s claim that foreign infrastructure investment fosters economic cooperation and mutual prosperity, it also masks the Party’s geopolitical purpose. When the loans can’t be paid back, Beijing is sure to come for its pound of flesh.

Debt can become equity, as in the case of Sri Lanka’s port, or it could be transformed into other forms of influence. Territories can be claimed. Maps can be redrawn. The Chinese Communist Party’s insistence that it controls the South China Sea, its sphere of maritime influence licking Southeast Asian shores, is no longer truly challenged.

If Colombo’s fold isn’t telling enough, look to Pakistan, where a gem of the Belt and Road Initiative is located. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is a $62 billion project that encompasses a deep water port in Gwadar, roadway projects, new railroads, energy sector constructions, and cooperation in agriculture and technology fields. In theory, the CPEC will bolster the Pakistani economy and allow China to access the Indian Ocean (which is of major interest to the Chinese navy).

On the ground, where there has been an influx of Chinese residents, integration has not been so smooth: the Chinese supermarkets stock pork, which is illegal to import or process under Pakistani law. Gwadar’s merchants say that the newcomers don’t shop from them. Chinese women sometimes don’t dress conservatively enough to match local customs.

For years, rebels in Balochistan province (where Gwadar is located) have been attacking CPEC’s installations and personnel, including targeted killings of high-ranking police officers, suicide bombings, as well as grenade attacks at eateries and workers’ lodgings. In July, Pakistan’s former prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for corruption. His political party, the Pakistan Muslim League–Nawaz, has been a key local partner in deals behind the CPEC.

Long Xingchun, a research fellow at the Chinese think tank Charhar Institute and the director of the Center of Indian Studies at China West Normal University, says that even though power is changing hands in Pakistan, it’s likely to remain business as usual for China: “Traditionally, no matter how Pakistan’s internal politics are shuffled, relations between China and Pakistan are not affected.”

For over half a century, the two nations have not only shared robust diplomatic and economic relations, but also intimate military ties. In particular, Chinese arms makers are Islamabad’s biggest weapons suppliers. The military connection is so favored that, as the story goes, a Chinese diplomat once told a U.S. official that “Pakistan is our Israel.”

Pakistan is no outlier. A 23-year-old woman in Sihanoukville, Cambodia, told The Guardian that she is learning Chinese to better integrate with the town’s newcomers, and lamented that “there will be no Cambodia left in Sihanoukville.”

I have ofen heard similar sentiments across South and Southeast Asia. During a stop at farms outside of Siem Reap, fishermen told me how their catch was shrinking rapidly, while farmers said they have been losing water for crops, all because of dam construction by Chinese firms along the Mekong River. In Dhaka, billboards and banners for Norinco—a Chinese weapons manufacturer and construction company—dominate; representatives of Bangladeshi construction companies gripe that the Chinese are handed the big contracts, including those for office buildings, hotels, and convention centers. I encountered the same complaints in the past two years in Vietnam and Burma.

Even with an abundance of red flags, Chinese investments around the globe are being pushed through. Xi is the strongest leader that the CCP has seen since its inception. Like Mao, he emanates a cult of personality, but without the bloodshed of the 1960s and ’70s. Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin implemented economic reforms in the following two decades, laying the groundwork to return wealth to the nation, allowing Xi to harness what has been amassed for global games. Hu Jintao modernized China’s infrastructure, which is now a key export to other nations under Xi. When it comes to statesmanship and governance, Xi is an authoritarian built for this century, and he has the resources to convert ambitions into reality—his and the Party’s.

As a world leader, the United States will not be displaced for years to come, but the erosion of American influence is fact, exacerbated by chaos in the current administration. Buzzy phrases like “America First” sound like war cries across the Pacific Ocean. “Death by China,” as espoused by Peter Navarro, who advises Trump in trade and industrial policy, cleaves apart the symbiotic relationship of the world’s two largest economies.

From the Obama administration’s “pivot” to Asia, to the now-defunct Trans-Pacific Partnership; from regular military drills with South Korea, to the presence of American military bases and troops in East and Southeast Asia; China’s policymakers see America’s actions in the past decades as a grand attempt to restrict the rise of the Party and the Chinese nation, but that containment has never worked. Instead, the foundations for a new world order have been laid.

This week, Xi returned to Beijing after a visit to four African countries over ten days—his fourth trip to the continent since becoming president. During a stop in Johannesburg, he called for BRICS to unfurl a second “golden decade” of cooperation. After the photo ops, commentators noted that Donald Trump has not visited the continent, and doesn’t seem to have plans to. With smaller, often indebted countries falling in line with China’s geopolitical agenda and BRICS nations securing regional power, the Chinese empire is set to be globe-spanning, robust, and impossible to hold back.