Like most Twitter users, photographer Chris Floyd had never met most of his followers. But then, last year, he unfurled a plain white backdrop in his West London studio and sent out a series of tweets inviting his Twitter friends to drop in for a photograph, a chat, and a cup of tea.

“I’m really, really nosy, and I wanted to see what all these people that I had begun to ‘talk to’ were like. I needed to meet them,’ says Floyd, whose work has appeared in Vanity Fair and The New York Times.

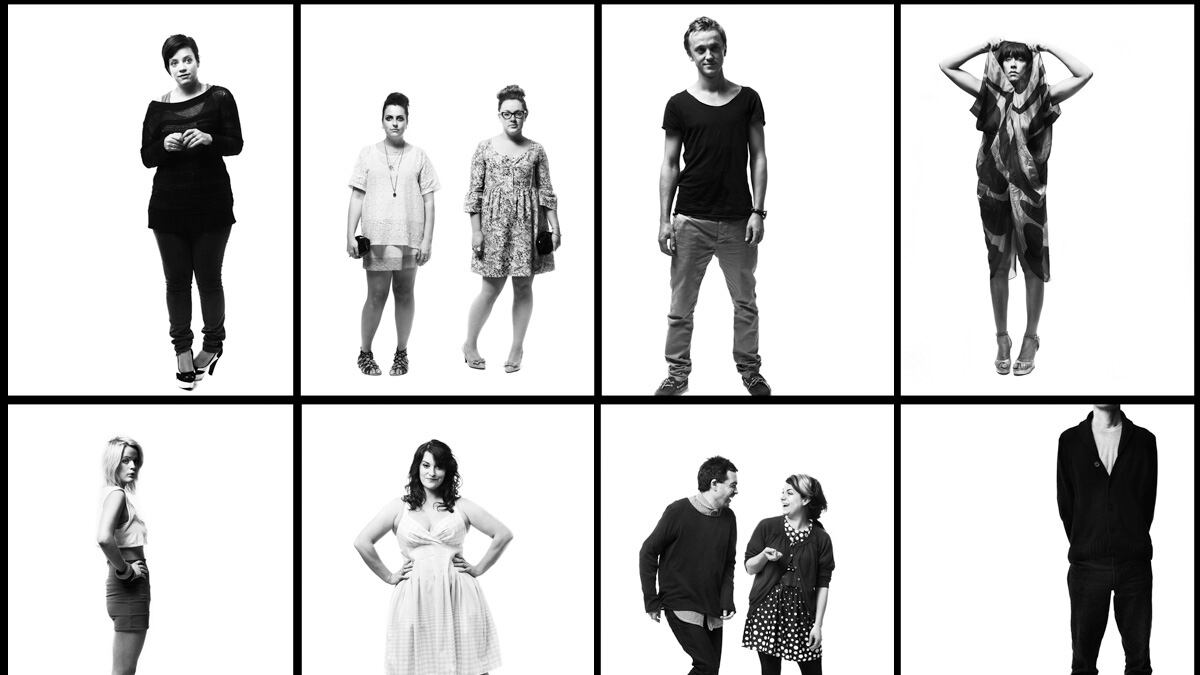

The project rolled on for almost a year, but one day, when he counted up the number of subjects photographed and came to a figure in the mid-130s, Floyd knew he was near the end. The resulting exhibition of striking black and white portraits, very different from the grainy lo-res headshots via which we normally view our Twitter interlocutors, launches at London’s Host gallery this Thursday.

The exhibition is called “140 characters,” of course. Among the chosen 140 are portraits of some of Chris’s higher-profile followers, including Lily Allen, Jimmy Wales, Pearl Lowe, India Knight, and Tom Felton (that’s Malfoy from Harry Potter to you).

Floyd started using Twitter two and a half years ago, when he received an automatic email alerting him to the fact that one of his friends had joined.

“For some reason I thought, Oh, sod it, I will sign up,” he says.

Floyd, a man not devoid of forceful opinions, as anyone who follows him @chrisfloyduk will know, soon realized he and Twitter would become fast and bonded friends.

“I started to use it a lot when I was sitting at my desk at home and listening to the radio,” he says. “Much of what constitutes me being at work—especially when I am editing photos—is vast swathes of time where I sit alone at a computer for hours and hours and hours. The furthest my intellect gets stretched during these periods is when I get to do ‘Ctrl+C’ followed by ‘Ctrl+V.’ So at first, it was just if I heard stuff that was funny or annoying on the radio, I would comment on it, and see other people’s comments.

‘That kind of banter was one thing I had always missed out on in my work life, because I had never shared an office or workspace. I realized, Oh, this is like having a workplace on tap. People to talk to and people who reply.”

At first it was just fun and diversion, but then Floyd started following the Guardian music writer Alexis Petridis and had another realization.

“He has a big column in The Guardian every Friday, and he writes about anything he likes,” Floyd says. “Like, maybe, the best 10 Philadelphia soul albums from the early ’70s. And I noticed that he was using Twitter for crowd sourcing. He would put out a tweet saying, ‘So I have albums by x, y, and z, but am I missing anything?’ Then 16 minutes later you’d just see another tweet from him going, ‘Thanks everybody, that’s brilliant.’

“He was leveraging his following. I started to do the same thing. Once, I wanted to know how to keep the shutter of my camera open for 45 minutes to photograph the night sky, and I asked Twitter how to do it and got the answer in seconds.’”

But why meet one’s followers? Isn’t the whole point of Twitter that we just give out edited versions of ourselves and receive edited versions of others in return? The highlights of humanity without the boring bits and the bad breath?

“You become curious about people who tweet in a funny or clever way,” he says. “Some people have mastered tweeting in the way other people have mastered writing haikus. You want to bathe in their glory, their funniness or cleverness—‘You’re really good, you cheer me up’—and the picture is just an excuse to justify an encounter. I love being a photographer because it’s a key that allows you to open doors into other worlds and have a bit of a poke about.”

Floyd says he didn’t end up disliking any of his Twitter-follower subjects, though a few got on his nerves. “There were people who were a bit annoying,” he says. “One guy talked so much that the photographer I shared the studio with actually sent me a text saying, ‘Please make him stop.’ But a lot of people who shine in the environment of Twitter tend to be shy. Big people in real life don’t need it, they’ve got a forum in the pub or wherever they go."

Floyd may love Twitter, but he’s no fan of Facebook, saying he’s “come to think of Facebook as the place where you go to tell lies to the people you went to school with, and Twitter as the place where you tell the truth to people you wish you had gone to school with. Facebook seems to allow the user to construct a perceived or projected existence for themselves through the deployment of various convenient aids, but Twitter just strips it all away and leaves the user with nothing but the utilitarian tool of 140 characters and the imagination of language. Over a sustained period of time you are always going to betray yourself. You will, layer by layer, reveal who you are.’

And what about the Twitter-phobes who say it’s all just a waste of time?

“Twitter is a huge, massive, endless free-flowing conversation with lots of interesting, witty people,” says Floyd. “What’s not to like?”