It’s already being hailed as a classic, and it was released only Tuesday. Building Stories features the stories of four people who live in one Chicago building. They lead quiet lives that we can all recognize, especially in the magnificent “Money” spread that so well captures financial desperation. But Ware’s artistry lies not in recognition but in complicating time and space—form—so much so that we can see these everyday, domestic lives as if for the first time. Building Stories gorgeously expands the graphic-novel form: it is a big box of treasures, consisting of 14 books, pamphlets, or posters of different sizes, and you can read them in any order. The narrative experience is fractured but strung together not by the act of reading one grid after another (although that happens as well) but by putting one book down and picking up another. He is “building stories” using new devices, and this allows us to experience the process of creativity.

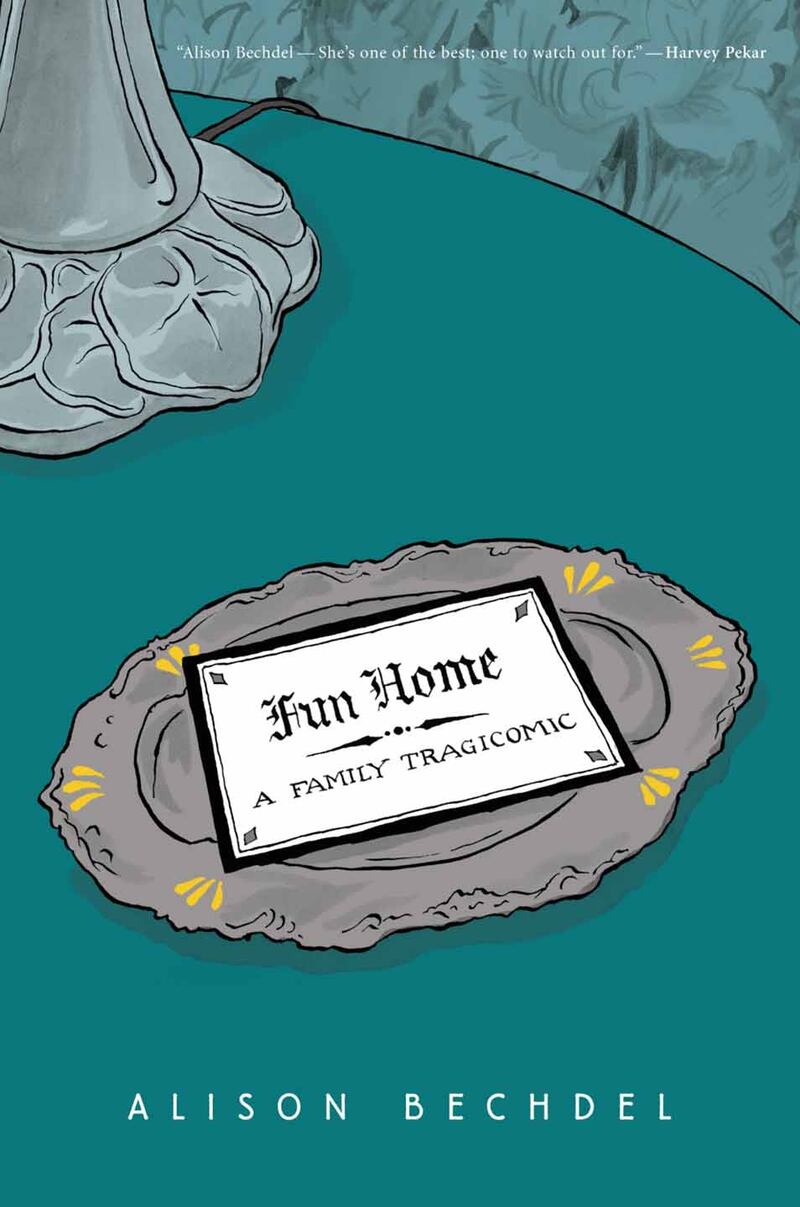

This approach to art Ware shares with the best graphic novelists of the times—they help us see and feel objects for the first time. From the proto–graphic novelist and expressionist artist Lynd Ward to the incomparable storyteller Alison Bechdel, here are 11 of the greatest graphic novels that every reader should turn to.

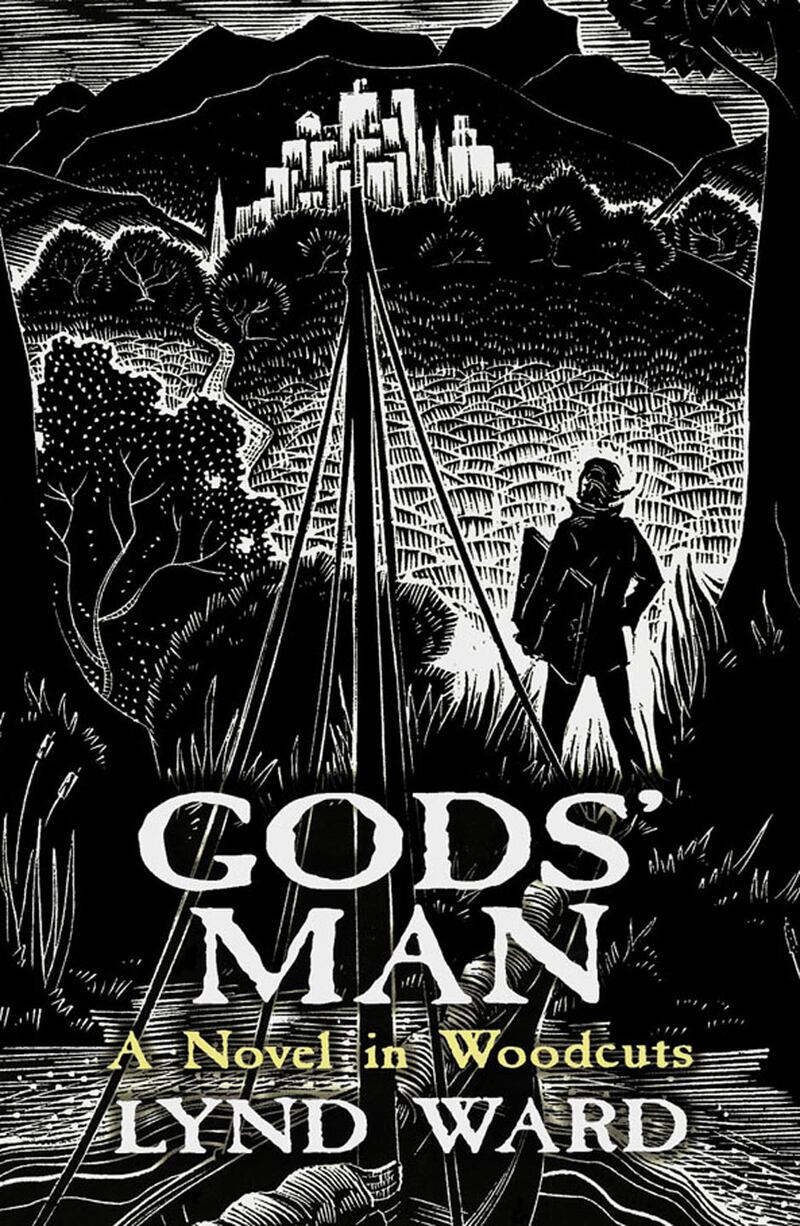

William Blake illustrated his poetry, and etchings and drawings have long decorated codices and been part of the art of bookmaking. But Ward’s wordless novels are among the first of such works, with a titanic influence on graphic novelists to come. Himself influenced by his European predecessor Frans Masereel (who created the wordless graphic novel Passionate Journey) and other members of German and Austrian expressionism, Ward’s wood blocks demonstrate the emotional power of the form.

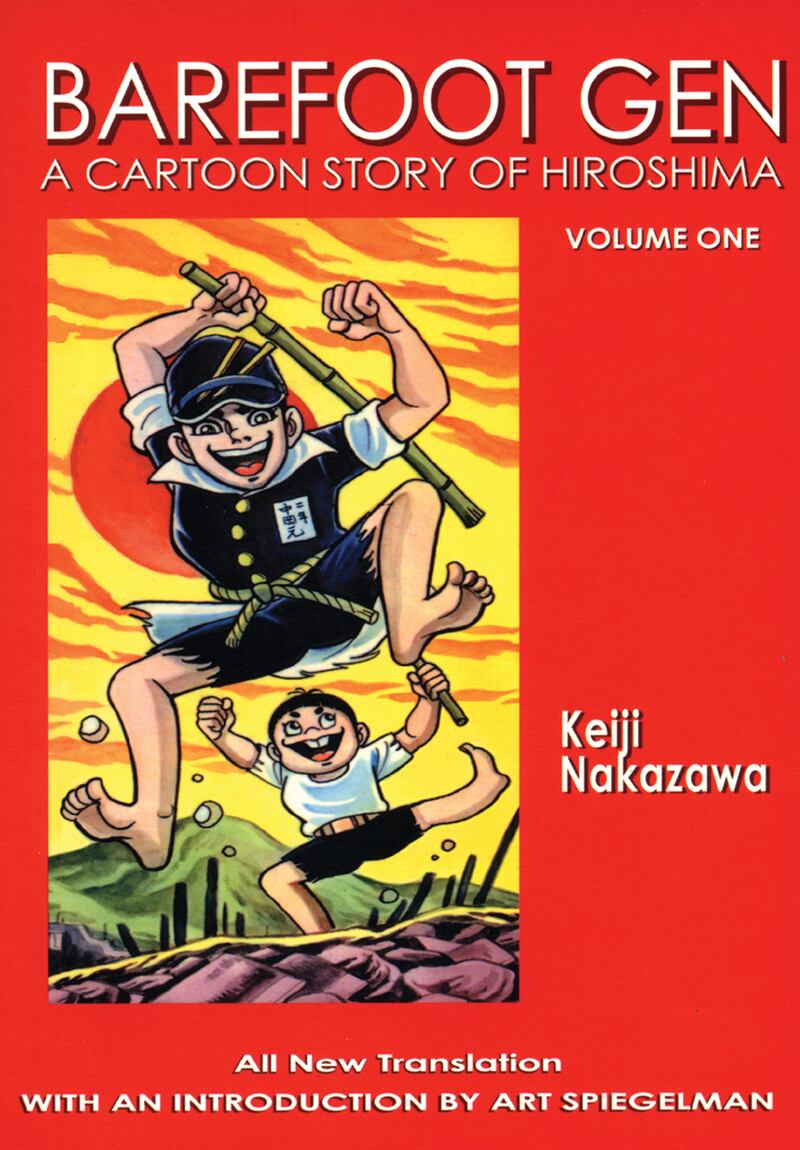

Comics were born in France and America, while Japan had manga, as the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction became increasingly fun, pop, or kitsch. In the 1970s, the Japanese cartoonist Nakazawa elevated the art of manga into the realm of literature. But it took a horrific massacre to do so. On Aug. 6, 1945, an atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Hiroshima. Nakazawa survived the catastrophe. Almost 30 years later, he set down the story of the bombing, giving birth to the modern graphic novel of “serious subjects” as we know it, though the “novel” is really a long-running series. Japanese manga has been criticized as exaggerated, but it proved perfect for conveying the emotions in this dark episode.

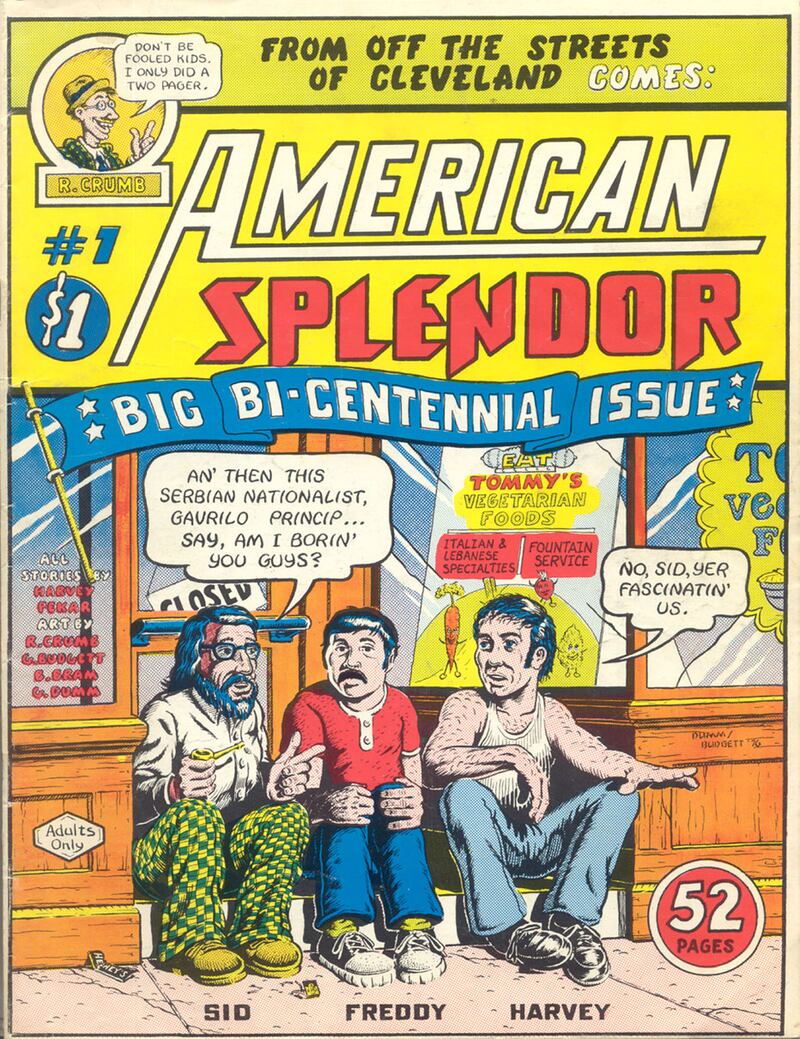

No survey of the art of comics could leave out Robert Crumb, whose dirty, pulpy Fritz the Cat helped invent underground comics and spring the form from formulaic superhero fantasy adventures. His friend Harvey Pekar wanted to use the form to tell human stories and asked Crumb to help illustrate his everyday life. American Splendor was born, and many great artists, including Alison Bechdel, Alan Moore, Spain Rodriguez, and Joe Sacco, would help illustrate the long-running series.

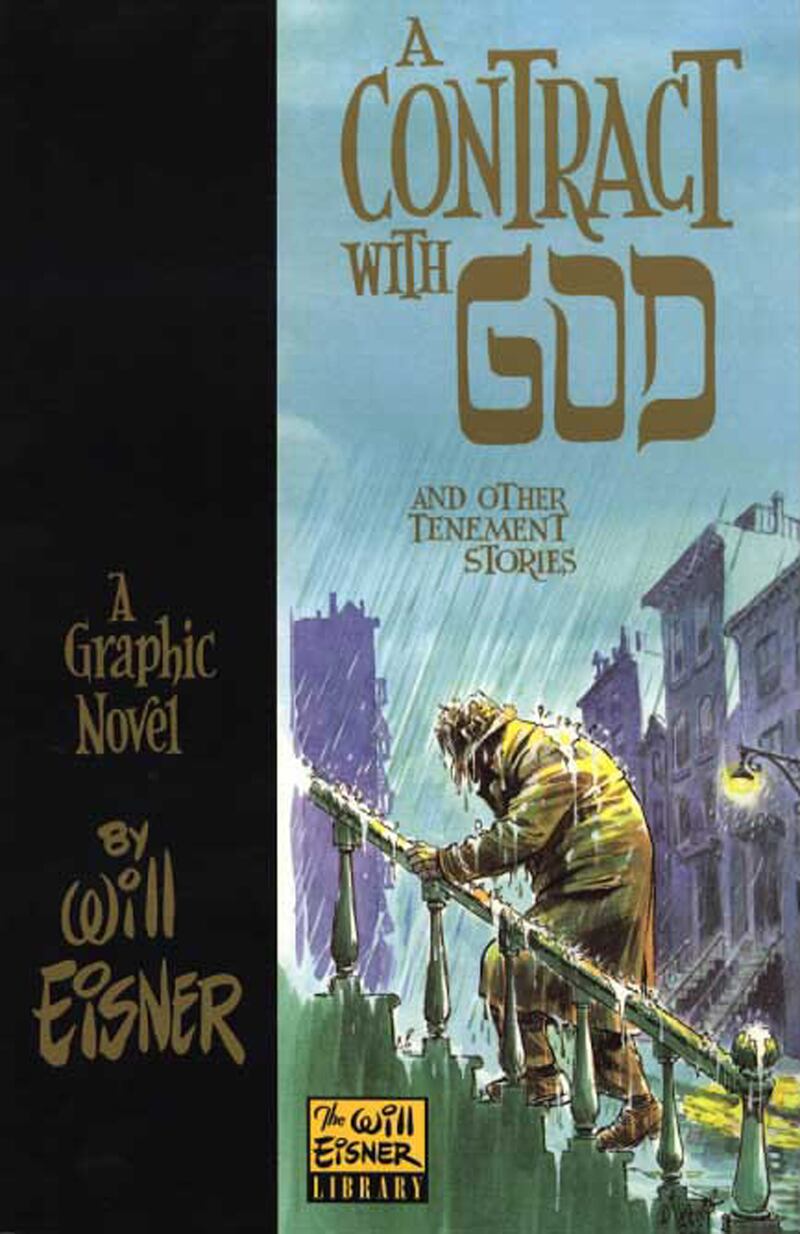

The creator of the comic book The Spirit was the first to call his own work a “graphic novel,” although A Contract With God is more a collection of four thematically connected stories, the first of which is about a Hasidic Jew whose adopted daughter dies. In 2001, Eisner revealed that his own teenage daughter died of leukemia in 1970.

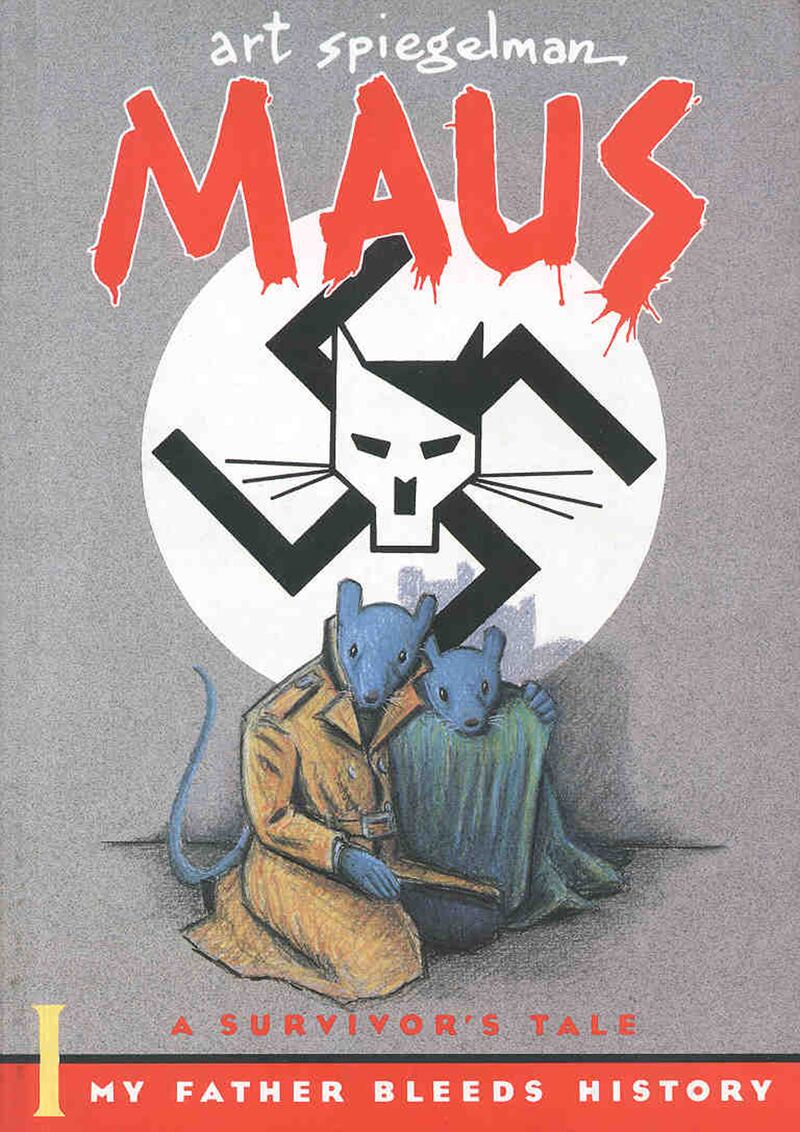

A descendent of Barefoot Gen, this is the first graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize. One reason it is so powerful is that while we all “recognize” the Holocaust, we have heard its stories so many times that we are desensitized by it. Spiegelman, in one of his many ingenious moves, depicts the Jews as mice, the Germans as cats, and the Poles as pigs. Like Tolstoy’s “Kholstomer” story, which is told from the point of view of a horse, the narrative is so estranged that we perceive it for the first time: it becomes something monstrous, something simple yet inexplicable—something like the Holocaust.

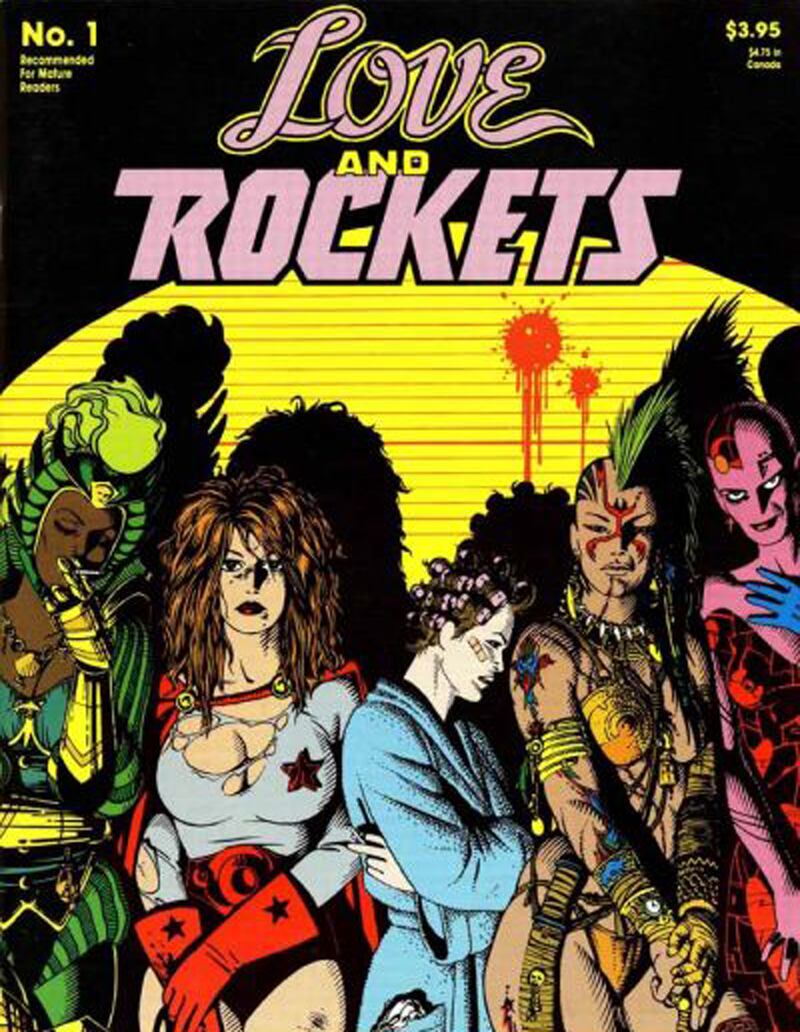

Comics was a very white world until the brothers Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez came around to portray the lives of Latino youths (who’d later grow up to be adults). And if you want to experience the punk and grunge life of the ’80s and ’90s, Jaime’s “Locas” stories is one of the best places to go to.

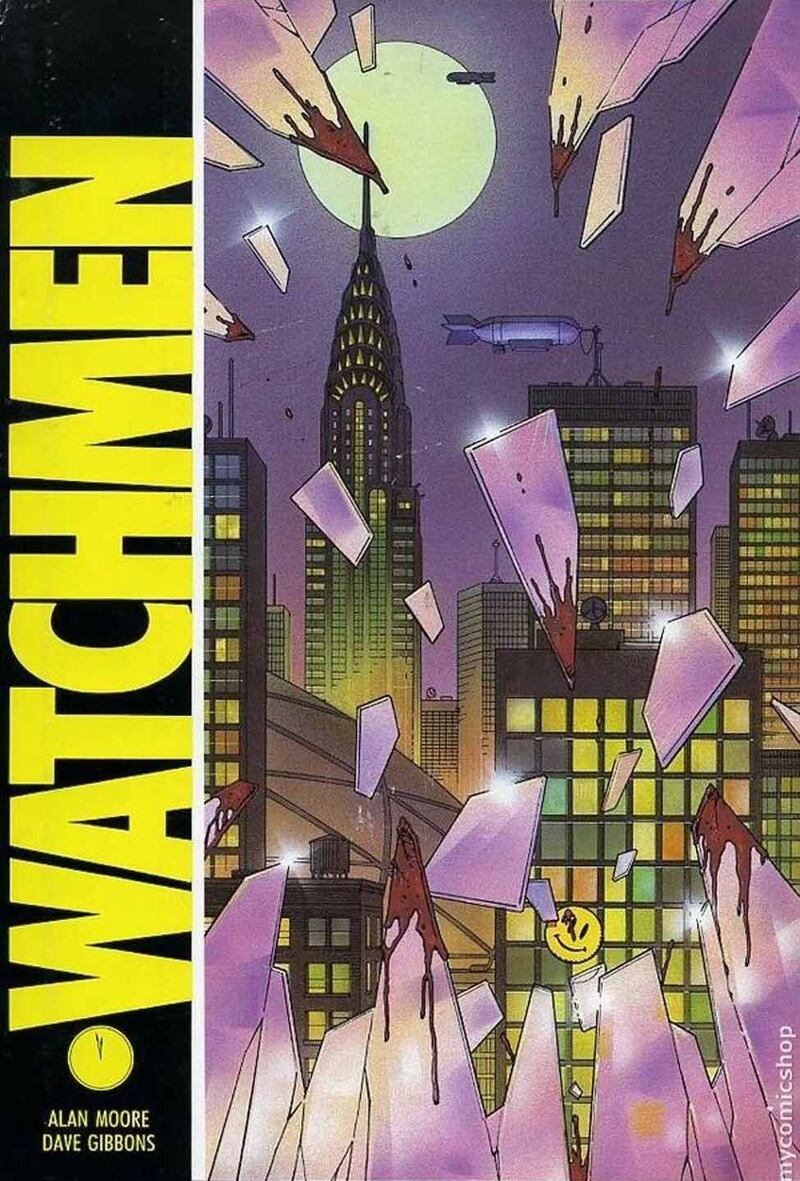

There are many comic series by Moore that we could pick, including The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, V for Vendetta, and the horrifying From Hell. But Watchmen continues to make a fierce impact, as Moore’s digressive, multilayered narrative confronts, head-on, the biggest monster of all in comics—the idea of the traditional superhero. Who watches the watchmen? No one, not in the real world.

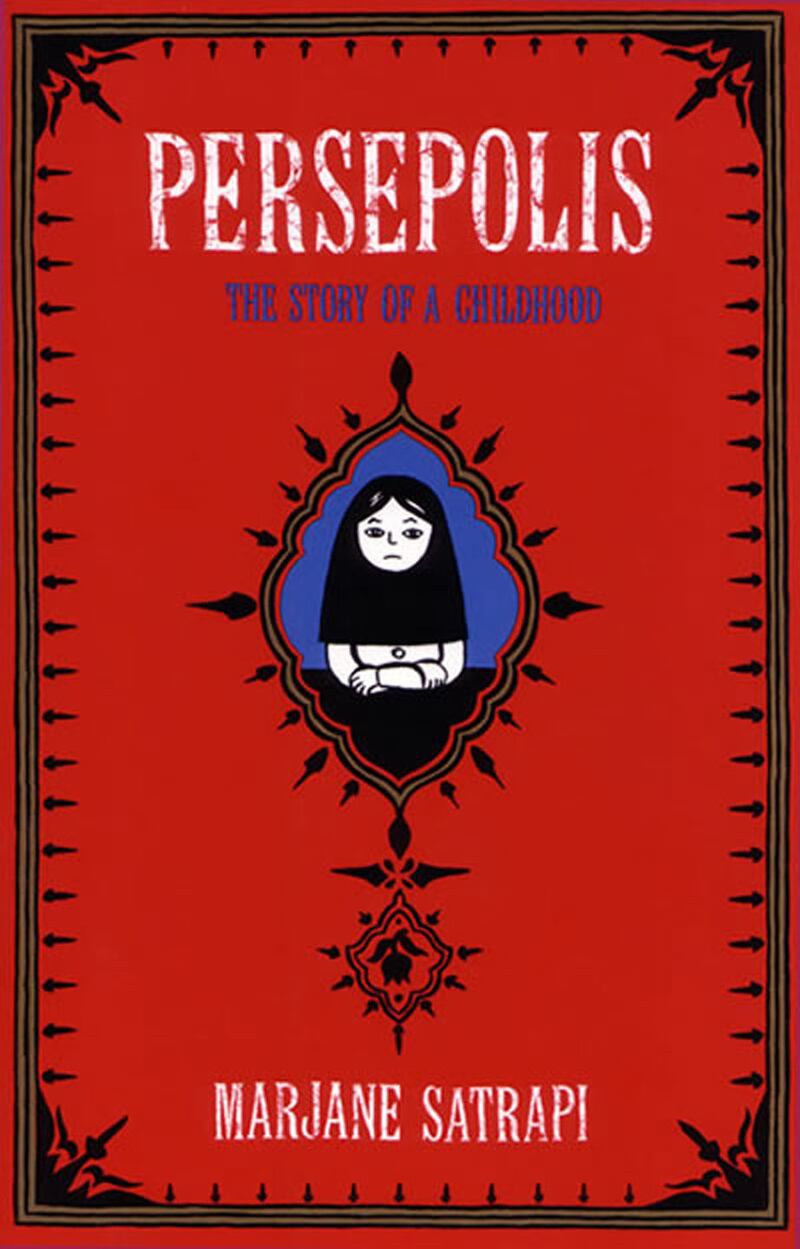

Where are the women in comics? Ah, here they are. What’s it like growing up as a girl in Iran? It might surprise you, as things are not always black and white, though the comics are drawn in sleek monochrome, paralleling the format of a revelatory memoir that Satrapi is so good at. Along with Lynda Barry, Phoebe Gloeckner, and Alison Bechdel, Satrapi and her fellow “graphic women” shine in a genre that is still made up largely of men.

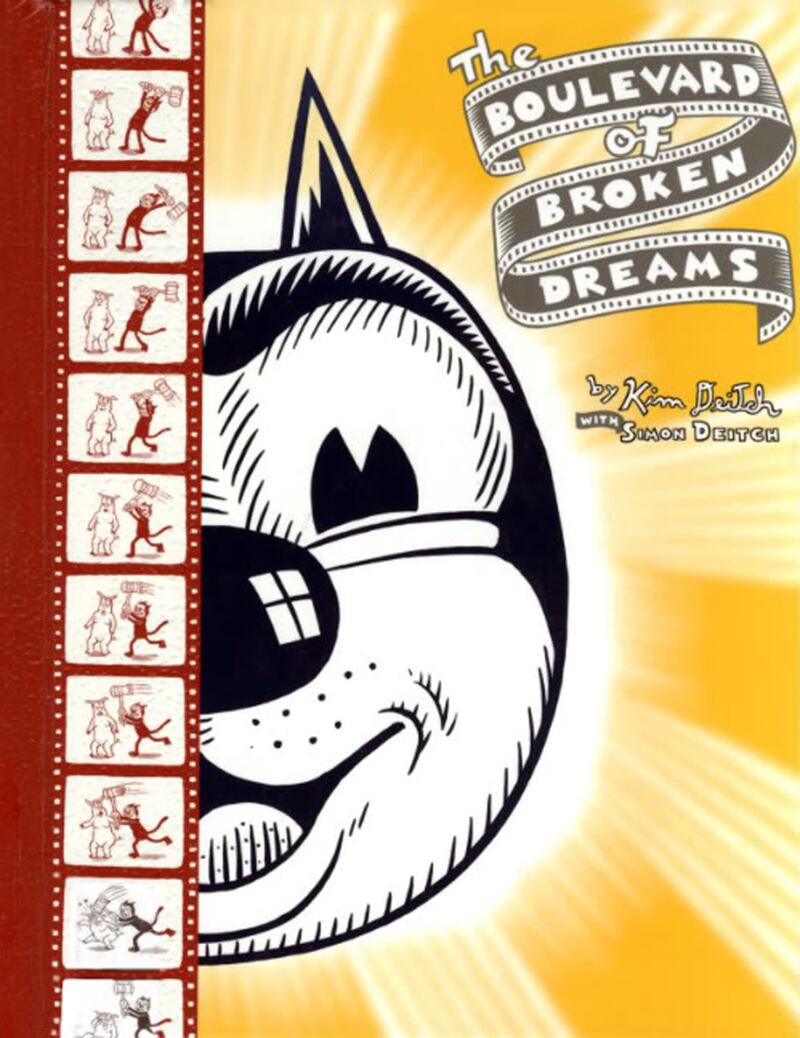

Dense, intricate, and always a ton of fun, Deitch is one the greatest underground comic artists you’ve never heard of. In Boulevard, Deitch folds the comic narrative on itself, portraying the story of an animation artist who finds that his creation, Waldo the Cat, is real—or perhaps surreal. His twisted madness is inky and hilarious.

Bechdel and her self-proclaimed “dykes to watch out for” revitalized and freed the graphic-novel genre by smashing through its macho barriers. Just when you think you’ve seen everything, Fun Home opens your eyes to Bechdel’s childhood in a small town, where she grows up to realize that she’s gay—and her dad is, too. The graphic novel is art not only in imagery but in images, in the economy of visual thinking. Bechdel and others represent the visual language at its best—familiar yet foreign, beautiful yet unsettling, somber and exciting and everything in between.