Christopher Durang, the playwright whose comedies viciously merged the satirical with the surreal, died at his Pennsylvania home on Tuesday night. He was 75.

The cause was complications from logopenic primary progressive aphasia, his agent, Patrick Herold, told the Associated Press. In 2022, the playwright’s family and friends shared that he had been struggling with symptoms associated with the condition for nearly a decade, though he wasn’t formally diagnosed until 2016.

Though his diagnosis led to his retirement from directing the Juilliard School’s playwriting program and slowed his output, Durang continued to write in his final years, adding two more plays and the book to a musical to a glittering, award-studded career defined both by its arch absurdity and sheer longevity.

“Christopher Durang was not only a giant in our field, but a guiding light whose daring works illuminated the stage with brilliance and wit,” the Dramatists Guild said in a statement. “His legacy as a playwright, lyricist, and educator is immeasurable, touching the lives of countless artists and audiences alike.”

A New Jersey native, Durang studied at Harvard before earning a graduate degree in playwriting from the Yale School of Drama, where he met one of his many muses, a budding actress named Sigourney Weaver.

“He’s so scaldingly funny,” Weaver told The New York Times in an interview on Wednesday. “You laugh with horror at what’s going on and your sheer inability to do anything about it.”

Durang broke through with 1979’s Sister Mary Ignatius Explains It All For You, an iconoclastic look at Catholic dogma that earned him the Obie Award for Best Playwright and the ire of the religious right. Asked in 1999 about audiences who were offended by his plays, Durang observed that his sense of humor “asks for a complicated response.

“I ask people to laugh at things that I know are also serious and tragic,” he continued. “And some people hate that. It’s like not wanting to mix your peas and mashed potatoes together—some people want them separate.”

In the same interview, Durang pointed out that “for every person bothered by my work, there seem to be five or six or seven who seem enthusiastic. Usually they’re mental patients. No, just kidding.”

One of these was his fellow playwright Stephen Adly Guirgis, who took to X on Wednesday to mourn Durang’s death. Guirgis recalled that he’d seen Sister Mary Ignatius in the eighth grade. “It blew my mind, broke my heart & made me laugh HARD,” he said. “All the reasons we go to the theater.”

Though Sister Mary Ignatius earned him his plaudits, he reached the arguable pinnacle of his career only decades later, with Vanya and Sonya and Masha and Spike, an acidic send-up of Chekhov’s plays that dropped like a bombshell on Broadway in 2013. Starring Weaver, David Hyde Pierce, Kristine Nielsen, and Billy Magnussen, the show won Durang the Tony Award for Best Play.

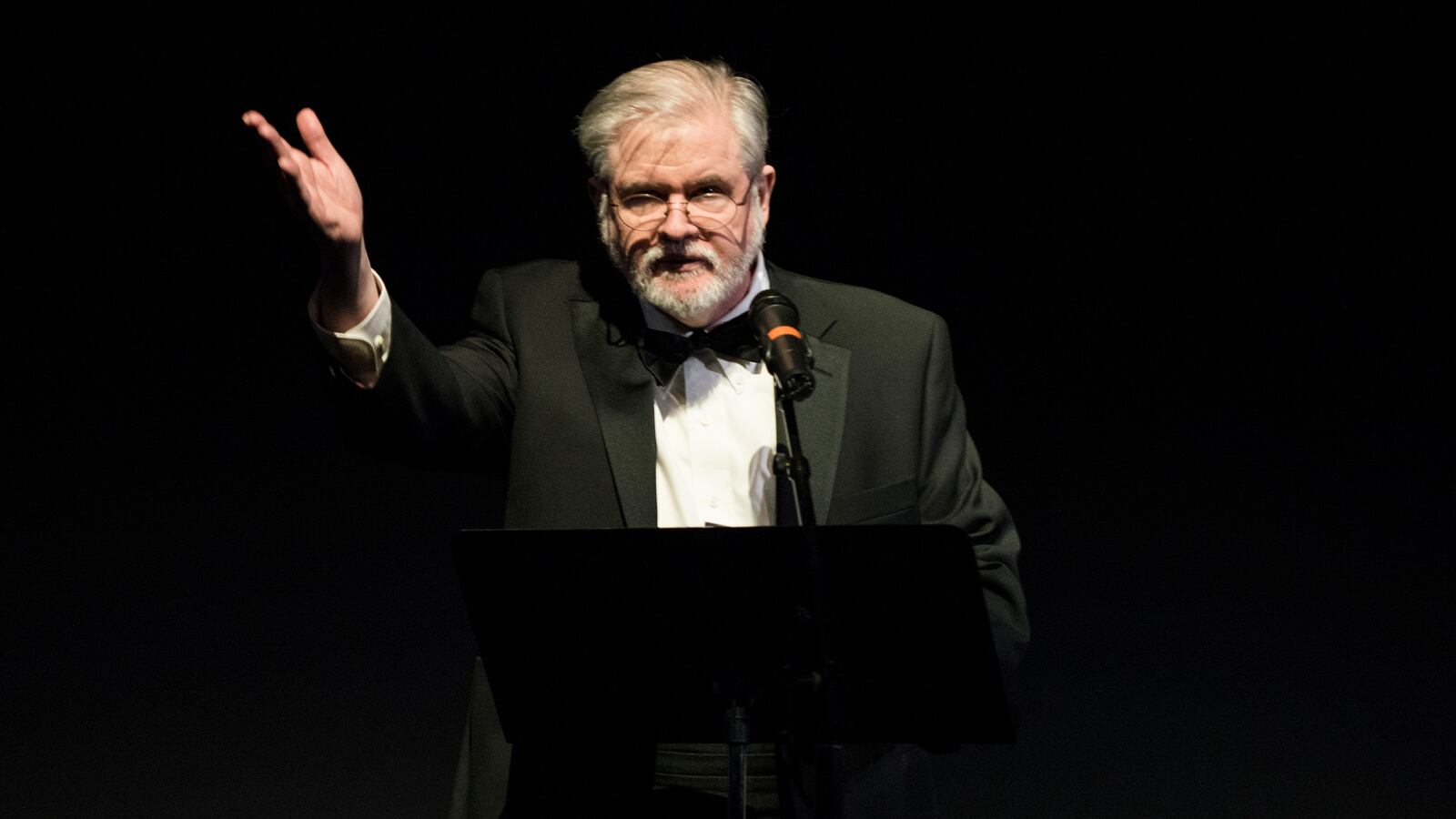

“I am very thrilled to win this,” Durang said while accepting the Tony. “I wrote my first play in second grade in 1958. It is now 2013. It’s been a long road, but I’m very happy to be here.”

In between, there were highlights like The Marriage of Bette and Boo, Betty’s Summer Vacation, Mrs. Bob Cratchit’s Wild Christmas Binge, and Miss Witherspoon, which made Durang a Pulitzer Prize finalist.

No matter the subject he picked to deftly lacerate—Catholicism, mental illness, family, middle age, murder, incest—each of Durang’s plays was shot through with a genuine pathos that would have his audiences reaching for the tissues when they weren’t doubled over in laughter.

“There was a darkness to some of his plays, and there was great humanity to some of his plays,” André Bishop, the artistic director of Lincoln Center Theater, told the Times. “He was a very, very funny writer. But what he wrote about and what lay underneath those plays was quite serious.”

Durang is survived by his husband of nearly four decades, John Augustine. Details of a funeral service will be kept private, but Herold, his agent, said that plans for a larger memorial service would be announced at a future date.