One of the problems with being an atheist is that so many of life’s salient moments have been defined in religious terms—baptism, confirmation, bar mitzvah, marriage, and, of course, death. In each case, religion has developed an enduring set of rituals, words, and associations which structure the experience of celebration or mourning. “How are we supposed to go about this?” is a question to which religion always has a ready-made answer. Consequently, even those of little faith will often find themselves, faute de mieux, promising to ward off the devil on their children’s behalf, pledging to remain wed till death do us part, and ultimately lying in a box whilst a man of the cloth bids us to meet our maker.

It is a thus a testament to the imagination of Christopher Hitchens’s family, friends, and colleagues that last week’s memorial service succeeded in transcending the traditional identification between God and grief. As the novelist Ian McEwan put it in a reading which attempted to channel their final conversations on religion:

“We are unlikely to cease making Gods or inventing ceremonies to please them for as long as we are afraid of death, or of the dark, and for as long as we persist in self-centeredness. That could be a lengthy stretch of time. However, it is just as certain that we shall continue to cast a skeptical, an ironic, and even a witty eye on what we ourselves have created.”

That skeptical, ironic eye was very much in evidence at a defiantly secular ceremony which was not without religious echoes. Orwell and Larkin thus alternated with the King James Bible, declaimed with aplomb by Christopher’s staunchly Christian brother, Peter. On the one hand, his “personal physicist”, Lawrence Krauss spoke of their shared contempt for “the intellectual laziness and pretentious nonsense that encompasses so much of religious faith and theological noise.” On the other, the director of the National Institutes of Health and “follower of Jesus Christ”, Francis Collins, recalled how Christopher had “graciously accepted” his prayers. “No doubt he now knows the answer,” he continued, “as to whether there is more to the spirit than nucleotides and neurotransmitters. I hope he was surprised.”

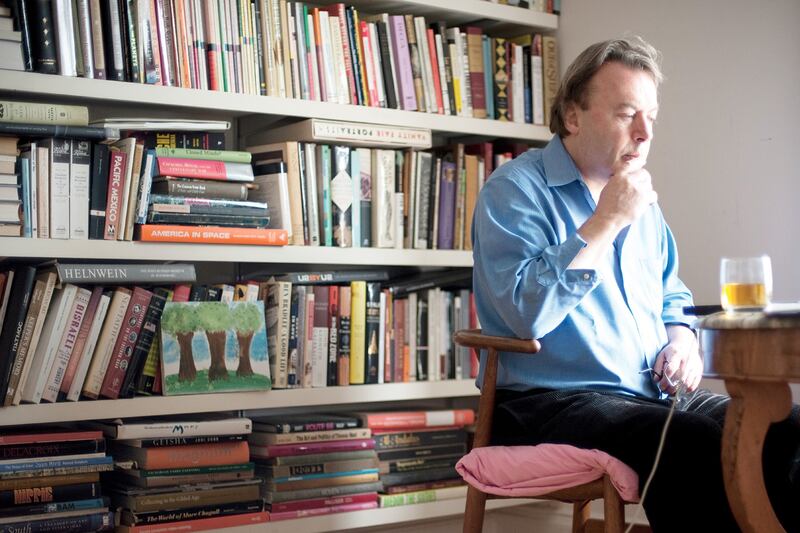

But while God may not have been entirely absent from the proceedings, Friday was really all about the Greatness of The Hitch. For two and a half hours, the man was remembered as a friend, husband, father, brother, and, above all, as a talker and writer of uncommon gifts.

Amidst a programme consisting mostly of readings from his own works, one got a sense of a man who had truly lived the great debates and controversies of his time—getting arrested by secret police in 1980s Prague; enduring bombardment alongside the beleaguered defenders of Sarajevo; excoriating his countrymen for their theft of the Elgin marbles; and documenting the human wreckage of American war crimes in Vietnam. All this was conveyed in a winning prose style defined by a singular blend of indignation and irony. As Martin Amis remarked in his eulogy, the young Christopher was fond of declaring: “Wherever there is injustice, immiseration, or oppression, the pen of The Hitch will flash in its scabbard.”

The Hitchens commemorated here was a man of the Left (like Orwell, Christopher insisted on the capitalization). Paul Wolfowitz was in the audience, but the service was dominated by the Hitch’s old comrades with nary a neocon among them. There were readings about the Arab Spring, Haiti, and the mendacity of Bill Clinton, but nothing about Iraq, which was mentioned only twice, first when Graydon Carter alluded to his “curious pro-war stance,” and again when Amis noted that he thought his friend was more conflicted about the war than he let on and that while “he was right most of the time”, he was also capable of “shackling” himself in a way that could defeat even the Hitch’s Houdini-like dialectical powers.

The rousing strains of the Internationale (in the original French) marked the beginning and the end of the ceremony. No one actually attempted to sing the workers’ anthem (the prospect of Anna Wintour exhorting “les damnés de la terre” to revolution would perhaps have been the point where irony descended into farce), but it served as a reminder that Hitchens really did used to believe, with Oscar Wilde, that a map of the world without Utopia was not worth consulting. His death heralds the passing of a generation—the soixante-huitards—for whom radical political change once appeared both desirable and feasible. That drama, with all its ironies, contradictions, and disillusionments, was the drama of The Hitch’s life. No one will ever get the chance to live another one quite like it.