“It is necessary,” writes Niccolò Machiavelli in his famous treatise on the craft of ruling, “to be a fox to discover the snares and a lion to terrify the wolves.” Shrewd statesmen from antiquity through the Florentine’s day and beyond have embodied this alchemical mix of the vulpine and the leonine in their quest to consolidate power, and their names gild our history books: Cesare Borgia. Catherine de’ Medici. Maximilien Robespierre. Mao Tse-Tung. Yet one iron-willed leader is conspicuously absent from the Princes’ Hall of Fame, at least in the West: that of China’s original ‘Dragon Lady’, the Empress Dowager Cixi.

Adored and feared during her Methuselian lifetime, demonized by later Republicans and Communists as a concupiscent tyrant who sold China out to the Europeans, Cixi has been an object of fascination and scorn ever since she seized the reins of the Manchu dynasty in 1861 in a carefully calculated palace coup. Still, despite a handful of attempts to sort through the myths surrounding her life and legacy, Cixi’s name has remained synonymous with feminine wickedness and imperial perfidy.

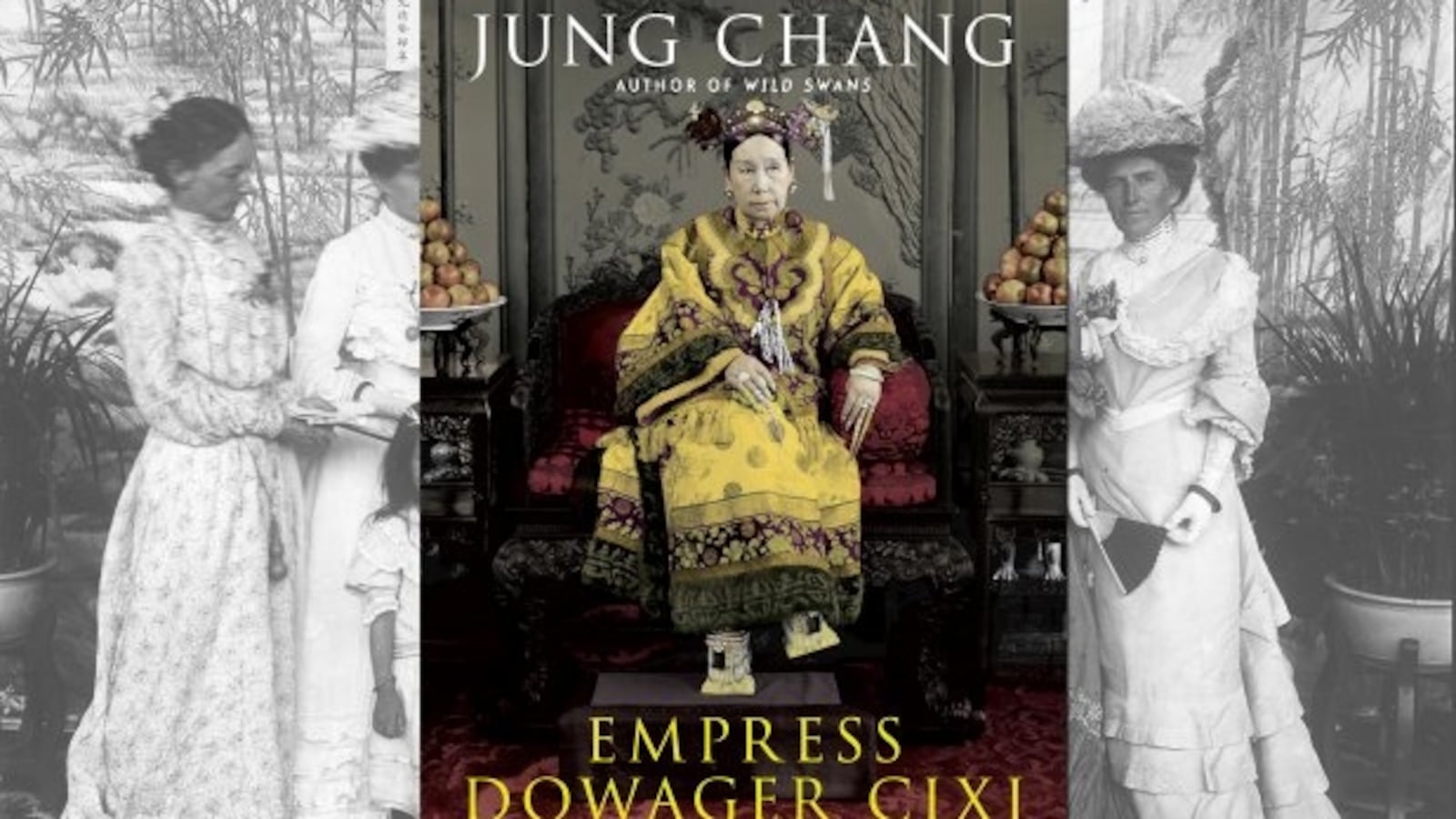

Enter Jung Chang, the London-based author of the best-selling Wild Swans and Mao: The Unknown Story, both of which remain banned in her homeland. Chang is a meticulous researcher, as displayed in her Mao biography, which was heralded as a magisterial work of serious scholarship (and which aired some of the Chairman's dirtiest secrets and worst atrocities). For her next act, she’s trained her sleuthing skills and piercing pen on the common concubine who rose to rule China, and what she’s uncovered is nothing short of imposing.

Empress Dowager Cixi is a hefty work, close to 400 pages total—by the midway point alone, Cixi is already 60 years old, with many assassination attempts yet to survive and massive reforms yet to wreak—as painstaking in detail as it is sweeping in scope. Chang captures the minutiae of court life—Cixi’s daily allowance of meat (70 pounds of pork, one chicken, one duck), the ‘sunset calls’ of the eunuchs—as well as the churning backdrop of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the Great Game was rushing to carve up Asia and restive rebellions roiled China’s countryside. Whether or not the book ever sees the light of day in Beijing and Shanghai, Chang’s new tome is certain to become the standard by which all future biographies of the Dowager Empress are measured.

Cixi’s early life hardly hinted at her flair for political intrigue and her intuitive grasp of the machinations of state and war. As a young woman in the ruling Manchu elite, she learned a smattering of Confucian texts and the finer arts of drawing and chess. Though not a classic beauty, at 16, she was considered refined enough to be enrolled in the nationwide selection for imperial consorts for the Emperor Xianfeng (nickname: “The Limping Dragon”). He chose her as a low-ranking concubine and she was shuttled off to the Forbidden City, destined to spend her days as a bored and pampered plaything in the hou-gong, or harem. Four years later, she gave birth to the Emperor’s first son, the future Emperor Tongzhi, which strengthened her position in the court.

The boy was raised jointly by Cixi and the Empress Zhen (“The Fragile Phoenix”), a mild-mannered woman who would become one of Cixi’s most important patrons and protectors. Inside the harem, the women were largely shielded from the turbulent events agitating China and jeopardizing the Emperor’s rule, but they surely gleaned a few snippets of gossip from the eunuchs: Famines. Floods. Droughts and downpours. The biggest peasant rebellion in the country’s history, the Taiping, aiming for secession in the south. British warships at the Dagu Forts, with London angry over the emperor’s anti-trade policy (particularly when it came to opium). A joint British and French force, led by Lord Elgin, 20,000 strong and bearing down on Beijing.

Xianfeng was a wrathful ruler, deeply resentful of the European powers that had weakened China in the Opium Wars during his father’s reign, and he surrounded himself with an inner circle that urged him to be uncompromising towards the Western armies. And so it was that he was genuinely surprised when foreign troops easily swept into the capital, forcing his retinue to flee and razing the spectacular Old Summer Palace—a marvel whose beauty caused even the worldly French to fall silent in awe and whose loss Cixi would forever mourn. Taking refuge in the royal Hunting Lodge, far beyond the Great Wall on the blasted Mongolian steppes, Xianfeng’s court suffered through a brutal winter. The Emperor took ill, and on his deathbed he appointed his insular Regents as guardians of his five-year-old son. “These were the same men who had helped Emperor Xianfeng make all his disastrous decisions, which ended with his own death," Chang writes. "Cixi could see that with these men in charge, stumbling along the same self-destructive road, there would be no end to catastrophe, which promised to destroy her son as well as the empire. She made up her mind to act, by launching a coup...”

The Emperor may have suspected Cixi’s designs on power, even though such a move—particularly by a female and a concubine—was stupendously foolhardy (traitors risked punishment by the dreaded ling-chi, or ‘death by a thousand cuts’). He wasn’t particularly fond of Cixi, describing her as “crafty and cunning"; apparently she’d tried to use their lovemaking sessions to meddle in political matters. He’d even issued an edict in secret to Empress Zhen, “saying that he worried Cixi would try to interfere in state affairs after he died, and if she did so, Empress Zhen was to show the edict to the princes and have her ‘exterminated’.”

Instead, it’s said that Empress Zhen quietly revealed the death warrant to Cixi and then cast into the fire. The two women began to plot, “often with their heads together leaning over a large glazed earthenware water tank, pretending to be appraising their reflections or just talking ‘girl talk.’” On the outside, they appeared compliant and deferential—vulnerable widows in need of the Regents’ advice. In secret, they arranged meetings with the popular and powerful Prince Gong, the emperor’s half-brother, who had been shunned by Xianfeng because of his soft stance towards the West. In a move worthy of seasoned schemers, Cixi and Zhen provoked the Regents into doing something illegal—they issued a petition that agitated the eight men, who threw a fit in front of the child emperor, a grave offense—and Prince Gong agreed to have the men arrested. The women handed down death sentences to some Regents and demanded that others commit suicide, thus smoothly taking power as their son’s guardians until he came of age.

As females, they were obliged to sit behind a yellow silk screen when they received dignitaries, but for all intents and purposes, the 25-year-old Cixi and her sister concubine were ruling a third of the world’s population from the confines of the harem.

Thus began a reign that stretched over 47 years and two sons, that weathered invasions by Japan and a coalition of eight Western powers, and that saw China transform from a secluded Confucian kingdom into a prosperous turn-of-the-century nation with modern cities, booming industry and a burgeoning middle class. For most of it, Chang says, Cixi was a fair and intelligent ruler, a far cry from how she’s viewed today. She was adept at projecting authority and encouraged dissenting voices within her circle of counselors. She knew when to back down from a hopeless fight—she declined to tussle with the French over the vassal state of Vietnam—and when to put on a show of strength, as when Russia tried to seize the province of Xinjiang, or when Italy demanded the rights to a naval station on Sanmen Bay.

Her motto, in the early years of her reign, was “Make China Strong,” and she advised her officials, “When it comes to China’s relationship with foreign countries, it is of course better to have peace. But before we can have real peace China must be ready to fight. If we give in to every demand, then the more we seek peace, the less likely we are going to get it.” Chang also uncovers convincing evidence that Cixi is to credit for the treaties in the 1880s that obliged Russia, France and Britain to respect China’s borders, at a time when the rush to gobble up faraway colonies was at its continental peak.

At her best, Cixi is painted as a ruler who embodied the ultimate Confucian virtue of ren, or benevolence. As an American diplomat to Beijing at the time observed, “To her own people…she was kind and merciful, and to foreigners she was just…and was regarded as being one of the greatest characters in history.” Cixi advocated the wisdom of choosing the right people and then sparing no expense to keep them happy, and over the years she pardoned many bureaucrats and even enemies whose offences might otherwise have led them to be jailed, or worse. Her equanimity won her the loyalty of high officials and common folk alike—a devotion that came in handy down the line, when she had to flee a besieged Beijing and rule from a proxy court in Xian.

Still, for a woman whose honorific name meant “kindly and joyous,” she was no pushover. True to the old adage that it’s better to be feared than loved, Cixi knew when to mete out punishments that would serve as warnings to her foes. After recapturing Xinjiang from a local warlord, she invoked ancient Qing penal codes to order his captured sons and grandsons to be castrated and given away as slaves. Years later, when her adopted son, the Emperor Guangxu, tried to restrict Cixi’s access to war reports, she had his favorite concubine roughed up and the girl’s eunuchs tortured until she uncovered enough dirt on Guangxu to blackmail him unless he stopped trying to cut her out of state decisions.

The same concubine, named Pearl, came to a grim end when the court had to flee Beijing in 1900: “With transport at a premium, Cixi did not want to make room for her” in the entourage, Chang writes, “but neither did she want to leave Emperor Guangxu’s favourite concubine and accomplice behind. She decided to use her prerogative, and ordered Pearl to commit suicide. Pearl declined to obey, and, kneeling in front of Cixi, tearfully begged to empress dowager to spare her life. Cixi was in a hurry, and told the eunuchs to push her into a well…[one of them] dragged Pearl to the edge of the well and threw her into it, as the girl screamed vainly for help.”

It was this kind of punishment that troubled Western diplomats—but, by and large, the Cixi era was remarkably pro-America and pro-Europe. Upon taking power, Cixi dispatched her trusted advisors to smooth over relations with Britain and France, and to solicit Western officers to train local soldiers in modern methods of warfare. As a result, the Brits—led by a swashbuckling general dubbed “the Chinese Gordon”—helped put down the Taiping rebellion and brought peace at long last to China’s countryside. Adopting the attitude that China should learn from the West’s successes—if only to make the country strong enough to prosper on its own—Cixi put an Ulsterman in charge of the Customs service, which was bogged down by corruption and inefficiency. Under his tutelage and Beijing’s new embrace of foreign trade, soaring revenues from duties poured into the empire's coffers.

Cixi used the newfound wealth to import food and stave off the cycles of famine that had wracked rural areas. She also invested in a modern navy and army and founded Tongwen college as a “model for a new educational system in the empire,” one based on science and industry rather than the 2,000-year-old Confucian classics that underpinned the entire Imperial Examination system. She sent court officials overseas to London, Paris, Washington and Moscow, where they mingled at royal balls and marveled at things such as electric lights (which Cixi would soon install in the Sea Palace) and railways (which the dowager empress desperately wanted to bring to China, but which the populace resisted for years because they feared rail lines would disturb ancestral tombs). During Cixi's early years behind the throne, China saw its first tram, its first “equal treaty” with a major world power (America), and its very first national flag. From her seclusion in the Forbidden Palace, Cixi issued a neverending stream of edicts, read the diaries of the travellers she sent abroad, and “steadily, yet radically, pushed the empire towards modernity.”

Not everyone in Cixi’s court was so pleased with Beijing’s new openness to foreign ideas. The esteemed teacher of Cixi's son and adopted son, Grand Tutor Weng, bemoaned the intrusion of the “stinking beasts” (as he called the Europeans, and particularly the Germans) onto Chinese soil—and he would instill that antipathy into Emperor Guangxu. Weng thought that the Westerners looked down on China as an inferior civilization, one to bully and threaten and pillage. A kindred spirit of Weng's, Prince Chun—who had married Cixi’s sister—preached revenge against the West for the razing of the Summer Palace, and advocated expelling all Westerners, boycotting foreign goods, burning foreign churches and sinking foreign ships. Chun is thought to have been behind the anti-Christian riots in 1870 that saw missionaries and nuns being lynched, mutilated, disemboweled and dragged through the streets naked. (Chun later repented for the violence and became a fierce ally of Cixi and her reforms.)

Most dangerously to Cixi and the Qing dynasty, anti-Western fever had reached such a pitch in 1900 that thugs calling themselves Boxers began attacking foreigners and pro-Western Chinese in the countryside and in major cities. By the spring of that year, the Boxer Uprising swept across China, with tens of thousands of peasants crowding the streets of the capital to sack the foreign quarters. Chilling reports leaked abroad about massacres of Christians (one such dispatch noted that a priest in To To had been publicly tortured, dismembered and set aflame in front of a jubilant crowd). Europe and America demanded that the violence stop. Cixi issued a tepid ban on the Boxers, but then—in an uncharacteristically indecisive move—she decided instead to organize some of the Boxers into an impromptu army, in order to dissuade the Western powers from once again taking Beijing. With the city's foreign legations under siege and 4,000 Chinese and Western Christians holed up in Beijing’s Cathedral, eight countries—including Britain and America—decided to invade. Cixi feverishly declared war on the whole lot, before fleeing with Guangxu and the court (though not the poor noyadée, Pearl) to the Boxers’ chants of “Kill the foreign devils” mere days before the foreign armies arrived.

Her handling of the Boxers was a rare misstep by Cixi, and for all her mastery of statescraft, she did have a few blind spots. She was fond of pleasure and spectacle—she loved the opera and penned original compositions to be staged by the eunuchs—and could be materialistic: after the occupation of Beijing, she seemed primarily concerned with the fate of the Forbidden City’s treasures, rather than the tragic loss of lives among her subjects. She also liked pomp and circumstance, even at inopportune moments—during the disastrous 1894 war with Japan (which, to be fair, Cixi had opposed, before being overridden by Guangxu), as China’s prized warships sank in battle after sea battle, she and the court seemed mainly preoccupied with arrangements for her sixtieth birthday. Chang tries to give Cixi the benefit of the doubt, but the episode is an odd one.

So is another incident—in which Chang takes Cixi’s side, perhaps a bit too forcefully—that involved the siphoning off of state money to build a new Summer Palace (“it seems that Cixi was troubled by what she was doing,” Chang offers). Most telling was Cixi’s unwillingness to relinquish power to her adopted son, Guangxu, when the boy came of age. At that point, Cixi was in the prime of midlife, having steered China for decades. True, Guangxu was an introverted and sensitive boy—his favorite pastime was to obsessively take apart watches and clocks—and probably unfit for the perilous waters of princedom, but it’s pitiable to watch the young emperor squirm as Cixi forces him into an unhappy marriage and later places him under a virtual house arrest. (Granted, the latter was retribution for his suspected involvement in an assassination plot.) She even made him call her "Papa Dearest" and "My Royal Father" in coerced Confucian filial piety.

Still, Cixi emerges from the book as the very model of a modern major empress, particularly in comparison to her two inept wards. Her biological son, the Emperor Tongzhi, had no stomach for ruling—instead, he liked to lounge at the opera, “reveling and frolicking with eunuchs,” before sneaking out of the Forbidden City at night to cavort with male and female prostitutes. He ruled for two stagnant years before catching either syphilis or smallpox and dying just short of his nineteenth birthday. In his place, Cixi installed an adopted son—in fact, her nephew by her sister and Prince Chan—the horologium-loving, painfully shy Guangxu. The boy was gullible, possibly impotent, and at odds with Cixi for much of his rule. His decision to go to war with Japan bankrupted the country, exposing it as a “paper tiger” to Western powers that proceeded to carve off parts of its territory. He also fell under the spell of a charlatan named Wild Fox Kang, who claimed to be a reincarnation of Confucius and dreamed of being emperor himself one day. Kang spearheaded an assassination plot against Cixi in 1898—one that was covered up for a century until historians pieced it together in the 1980s from the testimony of a would-be assassin in Japanese archives—and after fleeing to exile in Tokyo, he continued to bankroll mercenaries, rebels, pirates and other lowlifes to try their hand at taking out Cixi.

If this constant threat of death frazzled her, Cixi rarely showed it. She had nerves of steel, and the men in her court vacillated between kowtowing (literally and figuratively) before her and quaking under her gaze. The future first president of China, General Yuan Shikai, admitted that in her presence, “I don’t know why, but the sweat just poured out. I just became so nervous.” When Prince Gong condescended to her during her early days in charge, she sacked him for “having too high an opinion of himself.” (She let him return after he humbly prostrated before her, weeping and promising to reform.) Even though she had never seen the front part of the sacred Forbidden City, which remained off bounds even for dowager empresses, it was generally agreed that in her court, she was—in the words of a perceptive French visitor—“le seul homme de la Chine.”

In her later years, as the dynasty lurched towards its end, Cixi instituted a raft of reforms that Chang terms “the real revolution of modern China”. (The Communist censors will surely love that one.) In her zeal to “adop[t] what is superior about the foreign countries [to] rectify what is wanting in China,” Cixi lifted the ban on Han-Manchu intermarriage, tried to persuade the population to abandon the traditional practice of foot-binding, encouraged girls’ education (beneficiaries of her push included the future Madames Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek), did away with the ‘death by a thousand cuts’ and passed some prohibitions on torture, convinced Britain to end the opium trade, and pushed China closer to a constitutional monarchy based on the British parliament. She also launched a new campaign—“Make The Chinese Rich”—and encouraged the growth of private enterprise. She mingled with foreign guests, and even had her photograph taken with her favorite eunuchs. Cixi, and China, had come a long way from her first trip to the imperial harem.

Cixi seems to have sensed that the Manchu dynasty would not survive long after her death. As her health took a dire turn for the worse, she had Guangxu secretely poisoned with arsenic, in order to prevent him from colluding with Wild Fox Kang and the Japanese. (Other rumors abound that she also poisoned her first son and Empress Zhen, but Chang dismisses these as malice.) On her deathbed, Cixi turned the dynasty over to her two-year-old great-nephew Puyi, and made Guangxu’s widow the new dowager empress. In her final decree, she demanded that the next dowager empress would have final say in all important matters of state. Chang thinks that Cixi knew the Republicans would soon overthrow the monarchy, and wanted to put a woman in charge so that she could surrender gracefully. Within four years, the empress abdicated in the name of Puyi and transferred the right to rule China to a constitutional Republic. The reformers rejoiced. Meanwhile, in the countryside—according to Pearl Buck, the famed novelist who grew up as the child of missionaries during Cixi's rule—when the “peasants and the small town people” heard Cixi was dead, they cried out, “ ‘Who will care for us now’?

“This, perhaps, is the final judgment of a ruler,” Buck observed. There have indeed been many judgments passed on Cixi’s legacy, from the rumors (possibly spread by Wild Kang) that she was a sexually voracious despot to Chang’s final pronouncement that “the past hundred years have been most unfair to Cixi” and that “the political forces that have dominated China since soon after her death have also deliberately reviled her or blacked out her accomplishments…[but] in terms of groundbreaking achievements, political sincerity and personal courage, Empress Dowager Cixi set a standard that has barely been matched.” Cixi herself was obsessed with question, bemoaning during a low point, "What will future generations think of me?" Thanks to her long reign and beguiling complexity, that question will surely be debated for generations to come.