In response to a potential second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, New York City has decided to close down public school buildings. Many other big cities haven’t faced that choice, only because they chose not to reopen schools in September. However, the data to support school closures are limited at best, while the consequences of doing so will have repercussions for years to come.

First, children are at lower risk of infection than adults. In fact, with similar exposures children appear to be 50 percent less likely to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 than adults. In addition, among children who do get infected the disease course is often asymptomatic or produces mild symptoms compared to adults.

Second, the role that children play in perpetuating the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the general population is unclear. It is clear that children can spread the virus, however it seems that children do not transmit the infection as easily as adults do. Among schools in particular, transmission from children appears to be a rare phenomenon. Furthermore, a recent study noted that among numerous public health interventions that many countries have taken, the closing of schools has done very little to actually impact the spread of the coronavirus.

While some studies have found minimal or no transmission from students to teachers, some teachers may feel unsafe with in-person classrooms. Teachers did not sign up to be frontline workers. On the other hand, the economic and social consequences of school closures have been profound. Beyond education and support for appropriate childhood development through socialization and physical activity, schools provide numerous other societal benefits.

Over 11 million parents with school-aged children living in poverty depend on school as a form of childcare in order to go to work. The rates of food insecurity among children have increased dramatically. In addition, such closures are disproportionately affecting poor students and students of color who rely on schools for school-based nutrition, mental and physical healthcare. These children and their families are suffering as a result of closures that may not be contributing significantly to the control of the pandemic.

The question, therefore, should not be whether or not to close schools, but rather how do we safely keep schools open?

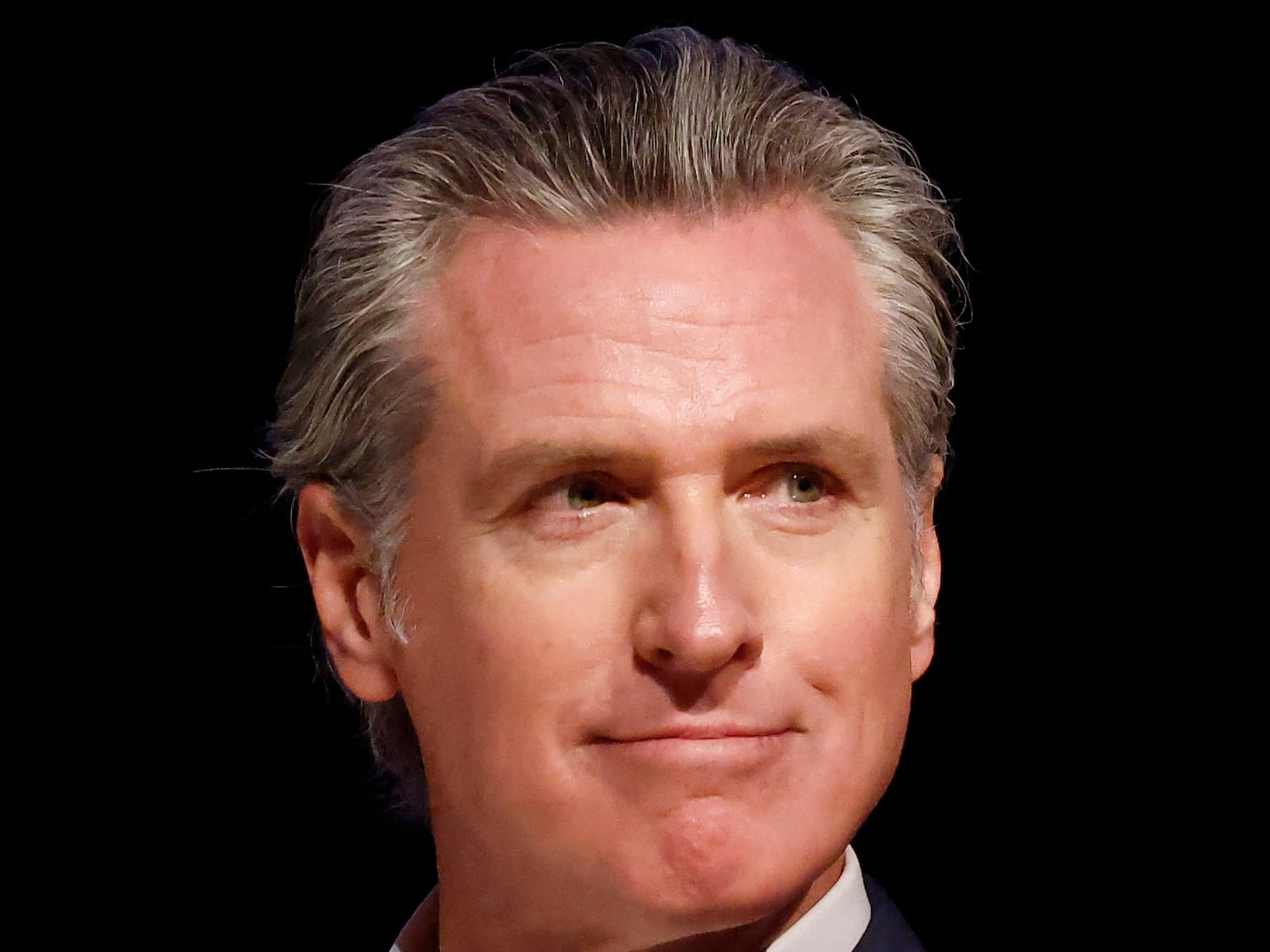

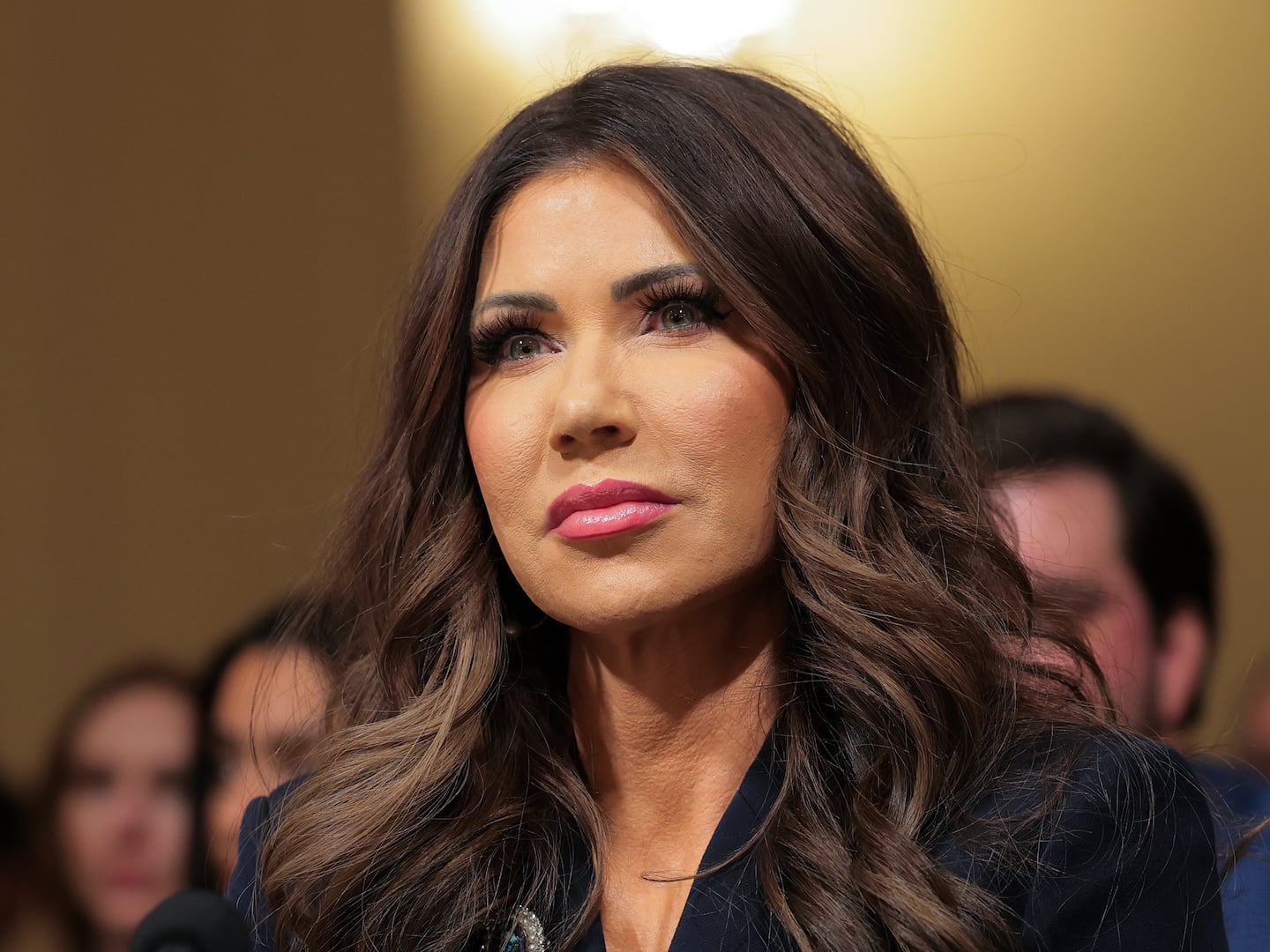

"Parents protest demanding that public schools remain open, outside New York's City Hall on November 19, 2020. - US coronavirus deaths passed a quarter of a million people on November 18 as New York announced it would close schools to battle a rise in infections."

Kena Betancur/GettyInfection surveillance is likely to be the most important way to keep children in school. Effective surveillance will require regular testing of all attendees—students, teachers and staff. Provision of sufficient testing kits and a means by which to receive a timely result is not trivial, and in fact is expensive. Therefore, an adequate supply of tests and materials must be ensured at a policy level.

In conjunction with regular testing, adequate contact-notification and supportive quarantine of those exposed or isolation of those infected is essential. Without appropriate support to facilitate quarantine or isolation, adherence to such measures is poor and suffering is increased.

It is critical that funding for such efforts be implemented at the state or even the national level, as significant disparities already exist between schools with varying levels of funding. Thus, without government support, it may very well be that already well-funded schools, which often teach more affluent students, are able to keep their doors open while under-funded schools, which tend to teach more poor communities, may be forced to close their doors. Such a scenario would only exacerbate existing disparities.

Children are at relatively low risk for contracting the infection, rarely have serious consequences, and do not appear to meaningfully contribute to the spread of the infection. In addition, the harm done both to the children directly as well as to the millions of families struggling to feed and take care of their children as a result of school closures are both immediate and long-lasting. We therefore need local and state officials to prioritize the development of a testing strategy specifically geared towards keeping schools open and children healthy.