July 4, 1976

Before terrorists used airliners as weapons, passengers were used as collateral. In late June 1976 Palestinian and German terrorists skyjacked an Air France jetliner that originated in Tel Aviv, eventually landing in Entebbe, Uganda. With backing from Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, the terrorists demanded that Israel release more than 50 comrades in exchange for the 250 passengers. As negotiations dragged on, 147 passengers were released, and the demand deadline was extended to July 4. But Israeli leaders secretly feared that caving to the terrorists’ would lead to more terrorist acts. A rescue mission rich with information from the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad was launched on July 4, with 100 to 200 Israeli commandos flying a distance nearly the length of the United States. All seven of the hijackers were killed in the raid along with three hostages—104 hostages were rescued. The Israeli force suffered one casualty—commander Yonathan Netanyahu, brother of current Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Operation Thunderbolt, also known as Operation Entebbe, is considered by many the most successful high-risk special forces missions in modern warfare.

John Plaster: “In the trade this was considered ‘a hostile environment,’ that is, the local government was not cooperating with the Israelis, requiring a stealthy infiltration into the country, and a synchronized commando attack on Ugandan MiGs at the airport, to secure a safe withdrawal. Very well done.”

May 1, 2011

The raid on Osama bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound wasn’t the most tactically complex mission, but in bringing down one of the FBI’s most-wanted criminals and arguably the most infamous man in America, the political ramifications of

bin Laden’s death make this mission one of the most successful ever. Two dozen elite Navy SEAL Team Six commandos in MH-60 helicopters—all told 79 soldiers and one dog were involved in the raid, according to The New York Times—were able to enter the compound under the cover of night and take out the notorious head of al Qaeda.

John Plaster: “Whether tracking POWs for rescue or terrorists for attack, most often by the time intelligence reaches those who can take action on it, it's too dated—the POW or terrorist has been moved, usually deliberately to thwart such raids. Bin Laden, it has been revealed, remained in one position long enough to find him."

January 30, 1945

No night vision goggles, no GPS units, no SOAR helicopter units—the raid to free hundreds of American war prisoners held by the Japanese at the Cabanatuan prison in the Philippines was a success thanks to a team of 14 Alamo Scouts, 120 Army Rangers, and 80 Philippine guerrillas. OK, and one technological ace—a P-61 Black Widow which flew over the compound and distracted guards while special forces moved in on the prison, quickly taking out the guards. The raid, near the end of World War II, showed American prisoners of war that they were not forgotten back in the States. The Army lost two Rangers, while two prisoners were killed.

Terry Schappert: “Looking back now, many people have never even heard of it. In a way, what did it accomplish politically for the U.S., the way the bin Laden kill did? Not much. But what it did do was it shook up the Japanese, it made them realize, ‘Oh my God, the Americans are at our back door.’”

April 12, 2009

The demands from the Somali pirates who took control of the cargo ship Maersk Alabama southeast of Eyl, Somalia, were not overtly ideological—there was no demand for the release of political prisoners or the like—they were monetary. But when the crew of 20 overpowered the four pirates, the pirates fled with Captain Richard Phillips in a covered lifeboat. The USS Bainbridge encountered the lifeboat on April 9, and the pirates demanded $2 million. After days of threats to kill Phillips, three Navy SEAL snipers

got the shots they needed when two of the pirates looked through a hatch while the third was visible through a window—the fourth pirate had already surrendered. In a split second the tense, four-day standoff was over.

Terry Schappert: “What was impressive was that they took out the three guys simultaneously from the boat, and everybody got rescued and nobody got hurt. So that bumps it up on the list of the most successful missions.”

March 1, 2003

A triumph of information more than a tricky tactical operation, the capture of one of the men behind the 9/11 attacks was a display of US inter-agency intelligence cooperation, and intelligence gathering efforts from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence. For all the satellite tracking and global positioning intelligence that went into the operation, Mohammed’s capture came down to a timely text message from an informant. The text

said: “I am with K.S.M.” Within a few hours Mohammed was captured at the home of Abdul Quddoos Khan, a bacteriologist who was likely working on biochemicals weapon, according to reports.

Col. Joe Felter: “It was such a big score for us as far as getting the 9/11 mastermind. It was just a real score for us. I’m not sure exactly all the intelligence we got, but it was apparent we got a lot of leads that led to other successes from that. It was a good example where maybe the Pakistanis were cooperating. It just took a lot of intelligence sharing and collaboration to pull that off.”

November 21, 1970

The objective? Rescue more than 60 prisoners of war from the Son Tay prison, roughly 20 miles from Hanoi in North Vietnam. The result? The Army Special Forces soldiers deployed to rescue their comrades did not find a single American prisoner at Son Tay (they had been moved). Still the mission is considered a tactical success. Guard towers were destroyed by helicopter fire and a convoy helicopter successfully crash landed in the middle of the compound—dozens, possibly hundreds, of enemy soldiers were killed while the American troops sustained only injuries. While the mission did not directly rescue any POWs, Operation Ivory Coast may have inadvertently saved hundreds of American lives. Afterward, the Vietnamese consolidated prisoners in Hanoi, and began treating them more humanely, with better food and living conditions.

Col. Joe Felter: “Bull Simons was in charge of it and he was a legend in the early special ops days. It’s always going to be a textbook example of early special ops.”

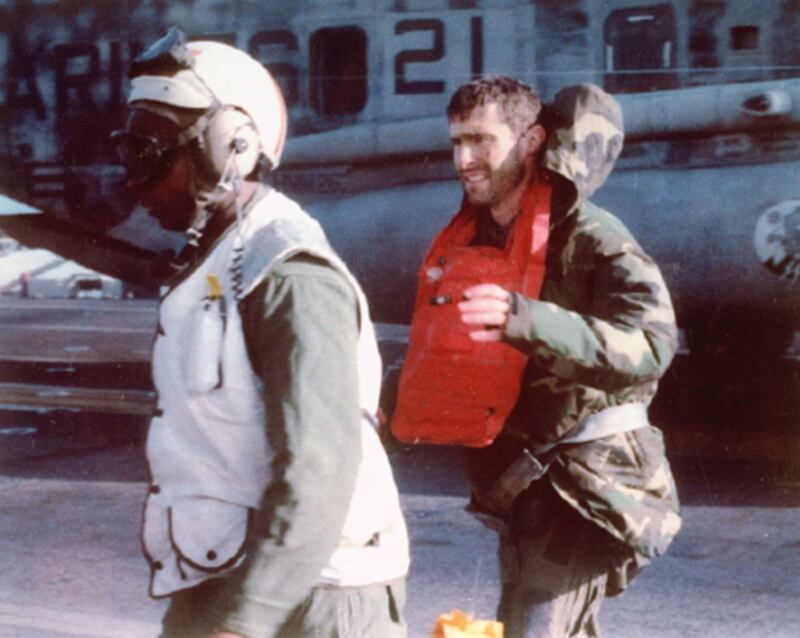

June 1995

Toward the end of the Bosnian War, Air Force Captain Scott O’Grady’s plane was shot down by a surface to air missile down while he was patrolling a no-fly zone over Bosnia. O’Grady safely ejected, but for nearly a week no one knew where he was, and he survived on whatever roughage he could find. Finally, technology came to the rescue, and O’Grady was able to contact nearby Marines via satellite radio. The rescue took 20 marines and 20 backup aircraft and, because of the potential urgency of O’Grady’s condition, the mission was conducted during the day. A few of the aircraft sustained damage, but no one was injured. The 2001 film

Behind Enemy Lines is loosely based on O’Grady’s experiences, and he later

sued the filmmakers for damages.

Terry Schappert: “Politically you probably see Scott O’ Grady and most people go, ‘Who the [heck] is Scott O’ Grady?’ But as far as the military goes he was ENE [Escape and Evade] for six days, basically eating grass, and he was doing everything right: hiding during the day and moving at night.”

April 1, 2003

Jessica Lynch’s rescue was presented by government officials and the press as a daring, high-risk endeavor more than a week after an ambush of Lynch’s company near Nasiriyah, Iraq that left nine Americans dead. Initial reports said there were signs that she had been tortured, and that the rescue crew of Army Rangers and Navy SEALs that saved her life had come under fire. But according to doctors and nurses there were no enemy soldiers, and Lynch was well-treated in the hospital she was taken to after the ambush, with one of the nurses going so far as to

describe a mother-daughter relationship with Lynch. Lynch, for her part, did not attempt to play down, or provide any direct insight into the perceived danger, or not, of the mission. She praised her rescuers but was critical of the media and military: “It does [bother me] that they used me as a way to symbolize all this stuff,” she

said.

John Plaster: “Initially it was presented by the media as an amazing raid and then when some of the details come out the same media were critical of it like it was inflated and not very real and an exaggeration. They don’t understand how these things are done—it was a real raid.”

October 3-4, 1993

Part of Operation Gothic Serpent, the Battle of Mogadishu specifically targeted Somali warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid for capture. The force of 120 Army Rangers, Delta Force, and Navy SEALs were caught unaware when two Blackhawk helicopters were shot down by rocket propelled grenades. On October 4 gruesome images of American soldiers’ bodies being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu made their way to the international airwaves. Although dozens of Americans and hundreds of Somalis died, a rescue crew was

able to save roughly 100 American soldiers’ lives.

John Plaster: “The fact that they got out of there reflected the quality of their training because many a force would have made a last stand there and been overwhelmed. But between Delta and the Rangers there, they fought their way out—and it was three dimensional. They had the enemy on three sides, and on rooftops, and they still got through. They fought their way out of an ambush.”

December 20, 1989

Part of Operation Just Cause, meant to oust Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega with nearly 10,000 American troops, roughly 50 Navy SEALs targeted Noriega directly for capture in Operation Nifty Package. Four Americans were killed when the SEALs attacked Noriega’s escape plane on a tarmac in Paitilla. Noriega escaped the attack, but famously emerged in January 1990 from the Vatican embassy he had forced to take him in. Reason was he’d had to endure days of popular rock music blasted by surrounding American troops.

John Plaster: “This was a bloody demonstration that ordinary (even mediocre) foreign forces can inflict cataclysmic casualties when a tactical mistake is made—advancing across flat, open ground, with no place to hide and no place offering cover from enemy fire.”

September 5-6, 1972

The 1972 Olympic Summer Games in Munich were supposed to help burnish West Germany’s image in the capitalist world. Instead, Palestinian members of the terrorist group Black September took 11 Israeli athletes hostage during the second week of the games. Munich police snipers, and the Munich police force in general, were overmatched and

unprepared to storm the terrorists at a moment’s notice. The 11 athletes died due to the botched rescue operation, which saw a lack of communication among the police and an underestimation of the number of terrorists, along with the death one police officer and five of the terrorists.

Terry Schappert: “In 1972 West Germany was so afraid of being looked at as a militaristic country—they wanted everyone to do the peace-love thing at the 1972 Olympics—so they had no ability or legal right to have the military be there, or have any response, so when this [situation] went down it was basically up to the military police. Within months of that happening Germany formed GSG-9. It got people thinking, ‘This is a problem we’re going to have to deal with in the future,’ so the government started to create anti-terrorist forces.”

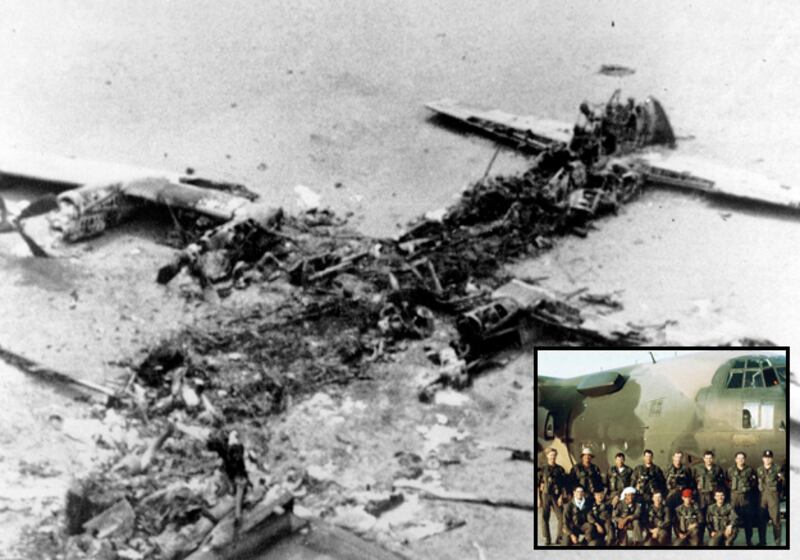

April 24-25, 1980

Operation Eagle Claw was influenced by Operation Thunderbolt in Entebbe, but the results were vastly different. Special forces were deployed to rescue 52 Americans being held at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. The first, and it turned out,

only step of the rescue—establishing a makeshift airstrip in a piece of desert believed to be uninhabited—was besieged by a dust storm and thrown off course when forces encountered a busload of civilians. In the ensuing chaos, a refueling helicopter with low visibility crashed into a C130 transport plane, killing eight. The remaining forces were evacuated, leaving a half-dozen helicopters in the desert.

Col. Joe Felter: “[Operation Eagle Claw was] the catalyst for creating special operations command and the inoperability between the different services. What you saw last week with bin Laden’s raid, there were different elements of special ops command and they had all planned together essentially for their whole careers.”

September 1-3, 2004

The most tragic of modern rescue missions began when nearly three dozen armed Chechen separatists took roughly 1,200 students hostage in a gymnasium laced with explosives at a school in Beslan, North Ossetia. On the third day, with negotiations at a standstill and the school surrounded by Russian forces, two of the gymnasium bombs detonated, setting off a firefight that allowed some of the hostages to escape in the chaos, but ultimately led to an urban battle that took the lives of between 300 and 400 people and left nearly a thousand injured.

Terry Schappert: “It shook up their security and political concerns, and basically the federal government under [then-President Vladimir] Putin consolidated a bunch of power in the Kremlin and the president in Russia was given a lot more power. So it made Russia a lot more authoritarian.”