A lot can change in 15 years. In 1999, the Cold War was over and everyone was talking about Francis Fukuyama predicting “The End of History.” Unemployment in the United States was at a record low, the dot-com boom was riding high, and for once the federal government had a budget surplus.

And people seriously had a problem with this.

When you’ve got a decent job with decent benefits, when the country isn’t at war, and the economy is doing well and your 401(k) is healthy, what do you have to complain about?

A lot, according to Hollywood.

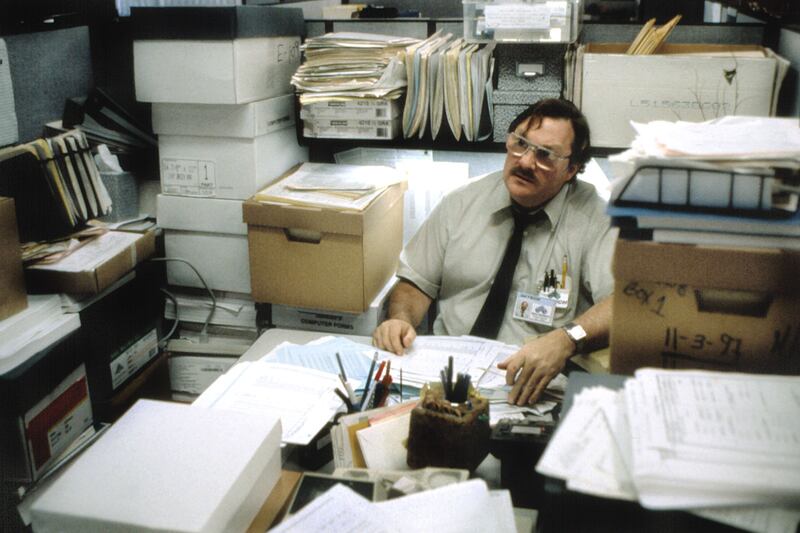

There was the Best Picture winner at the Oscars, American Beauty. There was the groundbreaking action/science-fiction franchise-maker, The Matrix. There was the dorm-room cult classic Fight Club and the endlessly quotable Mike Judge magnum opus Office Space. And all these films had as their protagonist a white male middle-class guy whose primary motivation is disliking the fact that he is gainfully employed at a stable, well-paying, boring office job.

Certainly in real life most of us would probably rate “boring office job” as a better life choice than “fast-food worker,” “pedophile,” “anarchist domestic terrorist,” or “guerrilla freedom fighter in a post-apocalyptic hellscape.” And yet Lester Burnham and Fight Club’s Narrator seem to get a spring in their step and a lightness in their heart from being liberated from making a decent paycheck and being able to afford groceries and mortgage payments. Hell, Neo throwing away material comfort in return for, essentially, living on a decrepit submarine comes with the reward of being able to stop bullets with his mind and fly.

What we have, in other words, in all of these films is a Hollywoodized Buddhist message that material comfort isn’t everything and that freeing ourselves from attachments to material things like jobs and mortgages is the key to true enlightenment and happiness.

… I know, right? If I have any millennial-aged friends around who care at all about movies, ripping into the 1999 I'm Employed, Boo-Hoo Tetralogy is a ritual. Going around in a circle talking about why we want to punch Lester Burnham in the face is classic generational bonding for us millennial film buffs at our social gatherings in our parents’ basements, as is waxing poetic about how much we’d like to escape into the Matrix, the simulated reality where the Machines keep us enslaved by giving us steady paychecks and nice apartments.

It’s not like the “boring office job” was even close to being a new topic for humor in 1999, or that it’s stopped being so since. At the time it felt like all of these “Revolt of the Cubicle Drone” movies were riding a wave begun by the comic strip Dilbert and that reached its zenith with the world-conquering popularity of The Office in the 2000s.

And yet, there's a critical difference. The dark paradox at the heart of most humor poking fun at soul-draining office jobs is that the person who most loudly and piteously laments their soul-draining office job is also likely the most terrified of losing it. Dilbert hit the big time in 1995, when the faddish word du jour was “downsizing,” and much of the humor at the time revolved around the constant fear of layoffs that haunted the engineering division of Dilbert and Wally’s unnamed company.

In the same way, both the original UK version of The Office in 2001 and its American remake in 2003 initiate the conflict that drives the plot by having higher-ups tell our protagonist middle manager that cutbacks and layoffs (“redundancies” in the UK version) are coming and forcing David Brent and Michael Scott to figure out how to relay this harsh news to their subordinates despite their total lack of people skills.

What’s most striking about the Tetralogy of White Middle-Class Complaining that came out in 1999 is that these films’ disdain for soul-crushing office jobs is so intense that they lose the angle of being desperate to keep the job that sustains your income even as it saps your vitality. The protagonists of these films seem to keep their jobs for no reason other than inertia, and they find self-actualization and happiness by, in fact, losing them.

American Beauty and Fight Club share the plot point of their protagonists walking off the job using the “severance package” of blackmailing their boss (a tactic that probably works less smoothly in real life). American Beauty’s Lester Burnham leaves his advertising job to work at a fast-food drive-thru and leer at his daughter’s best friend. Fight Club’s unnamed narrator abandons the auto industry in favor of life in a decrepit slum squat making soap and explosives in his basement. Neo in The Matrix runs off from his software design career to live in a hovercraft eating processed protein gunk and constantly run for his life from mechanical tentacle monsters known as Sentinels.

They take part in an ancient philosophical tradition, going back to Henry David Thoreau, to the Buddha, to the Book of Ecclesiastes. They consider the fruits of material prosperity, dismiss them as “vanity,” and storm off looking for a higher spiritual fulfillment.

It’s a powerful message, and one with merit, or films like this would never have resonated with so many audiences. And yet it immediately sparks the reply—well, the country sure has gotten way more enlightened since 2009, huh? Should we be thanking the Wall Street masterminds who engineered the financial collapse that has forcibly “freed” so many of us from our material comforts?

It’s hard to watch any of these films without cringing at least a little today. Fight Club is least offensive (in my eyes) because it doesn’t shy away from how ugly and insane Tyler Durden’s revolution becomes, and yet when Durden pontificates about how “our generation” has suffered from having “no great war and no great depression,” members of my generation get to look at our friends and classmates who came back from Iraq and Afghanistan to find no jobs waiting for them and wonder what the hell he’s complaining about.

To say nothing of the privilege on display in American Beauty when Lester Burnham liberates himself from the need for material things by, like many midlife-crisis survivors, already having plenty of money with which to buy himself material things. (How can you simultaneously have your protagonist mouth off at his wife for being a greedy materialist while also blowing his savings on a brand-new Pontiac Firebird?) And as far as The Matrix even has a social message it ends up being one about how a few people in possession of secret religious knowledge are truly alive and all the other working-stiff drones are leading dead, meaningless lives—and therefore working-stiff security guards and police officers are acceptable collateral damage when our heroes gun them down by the wagonload. It's a message that goes down a little less smooth after 9/11/2001.

***

While Office Space stays committed to its “office jobs suck” ideology, it has the courage to challenge it. Unlike the other three films, Mike Judge’s masterpiece shows our protagonist Peter’s coworkers genuinely fearful of being downsized, even as Peter’s hypnosis-induced faux-enlightenment makes him blissfully careless about his job security. Yes, Peter does eventually find happiness quitting an office job for blue-collar construction work, but not before Peter’s neighbor Lawrence points out that construction work is, in fact, grueling and exhausting and expresses confusion at Peter’s weird middle-class idealization of it. Just as Peter’s girlfriend Joanna brings up the obvious fact that people do crappy jobs because they need money and that having to do a crappy job because you need money is not the equivalent, as Peter claims when he goes off the rails, of being imprisoned in a concentration camp (an equivalence that films like The Matrix jump right into).

Because let’s look at what was actually going on in 1999. Yes, office jobs are frequently stifling and pointless and, as the protagonists of all four films would agree, we were probably put on Earth to do something other than shuffle papers all day. A world where everyone had to work at a crappy office job all day would be a pretty lousy world and if we somehow got our shit together enough to offer everyone a crappy office job we’d still have a long way to go toward making the world a decent place.

And yet. Even in 1999, this gilded cage of a cushy but unstimulating white-collar career was only available to certain people. That 4.1 percent unemployment wasn’t evenly distributed across the nation. The unemployment rate for African Americans was about double that, at 8.1 percent, and this was celebrated at the time as a record low. Think about that—when the overall unemployment rate exceeded 8 percent in February 2009, that was considered a national emergency. America as a whole having more than 8 percent of its people not working is an emergency; black America having only 8 percent of its people not working was a triumph.

It’s not just race, of course—there are people of every race for whom the ennui of an unfulfilling office job would be a nice problem to have. But there’s certainly a ring of truth to the accusation that Occupy Wall Street only became a thing after the demographic of white, middle-class college graduates who always took it for granted that they had those “boring” office jobs waiting for them started to feel the pinch.

Sure, now the “stifling office job” is passé. Our science-fiction epics aren't about the excitement of escaping middle-class comfort into a “real world” of action and violence; we have Elysium and The Hunger Games, stories where the protagonists hail from the impoverished underclass and fight out of desperation to better their lives.

This won’t last. There's a certain kind of person—white, upper-middle-class, from LA or NYC—who’s, demographically speaking, more likely to end up calling the shots in media and they follow the dictum to “write what you know.” Sometimes you get exceptions and those exceptions become hits—from The Honeymooners to Good Times to Roseanne. More often you don’t, and you instead deal with Rich People Complaining About Being Rich.

The specific form this took in the 1999 Complaints of the Employed White Guy tetralogy was interestingly unique to that year, but the overall theme is quite familiar. 99 percent of everything you read in a high school English literature class is about privileged people complaining about their privileged lives, including the works of Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and Tolstoy. The whole history of Western film and TV is mostly the travails of wealthy people with problems only the wealthy can understand. (Hell, I was named after a famous lovably dysfunctional millionaire.)

And, indeed, many pop-cultural attempts to wrestle with our “post-recession reality” have received blowback because they imagine a reality where the safety net and connections that come with white, middle-class privilege are taken for granted. See the enormous backlash against Girls.

Look, I actually like Girls. Hannah’s problems aren’t any less problems because they’re “white girl problems” or “First World problems.” And speaking as someone who recently got a lot of money, the fact that emotional difficulties only multiply as your physical obstacles vanish is something I’ve experienced firsthand, and has been lamented in songs both old.

I don’t condemn anyone for coming to the same realization the Buddha did, that material comfort in the form of the IKEA catalog (Fight Club) or Italian sofas (American Beauty) ain’t all that. But the Buddha condemned both extreme luxury and extreme poverty as obstacles to enlightenment. None of these office-worker rebels would be able to finance their little revolutions if they hadn’t started with means, not even Neo. (How do you attract Morpheus’s attention if you can't afford a computer and Internet connection?) I do my fair share of complaining now, but I try to keep in mind how irrelevant and obnoxious my complaints would be to my past self in 2010 struggling to make rent on an hourly wage.

We’ve made progress since 1999, mostly in the form of regress—as the pain of recession hits a wider swath of Americans, more people start talking openly about money problems, and that includes movers and shakers in media. But it’s still a sad state we’re in when the Emmy-winning comedy is about a family of apparent millionaires who can, for instance, wreck the family car on the regular for laughs without apparent consequences, and the best our generation can do in response to The Honeymooners or Roseanne is (ugh) 2 Broke Girls.

Perhaps it’s time we put 1999 further in the distance in the rear-view mirror in the next 15 years. Money can’t solve all the problems of the human condition, but money (and its lack) is, itself, one of the greatest problems of the human condition. For our storytelling to be truthful we need to address this fact, not turn away from it.

Otherwise, our culture will continue being one where the elite bask in the luxury of struggling to find their purpose in life while the rest of us just struggle to live.