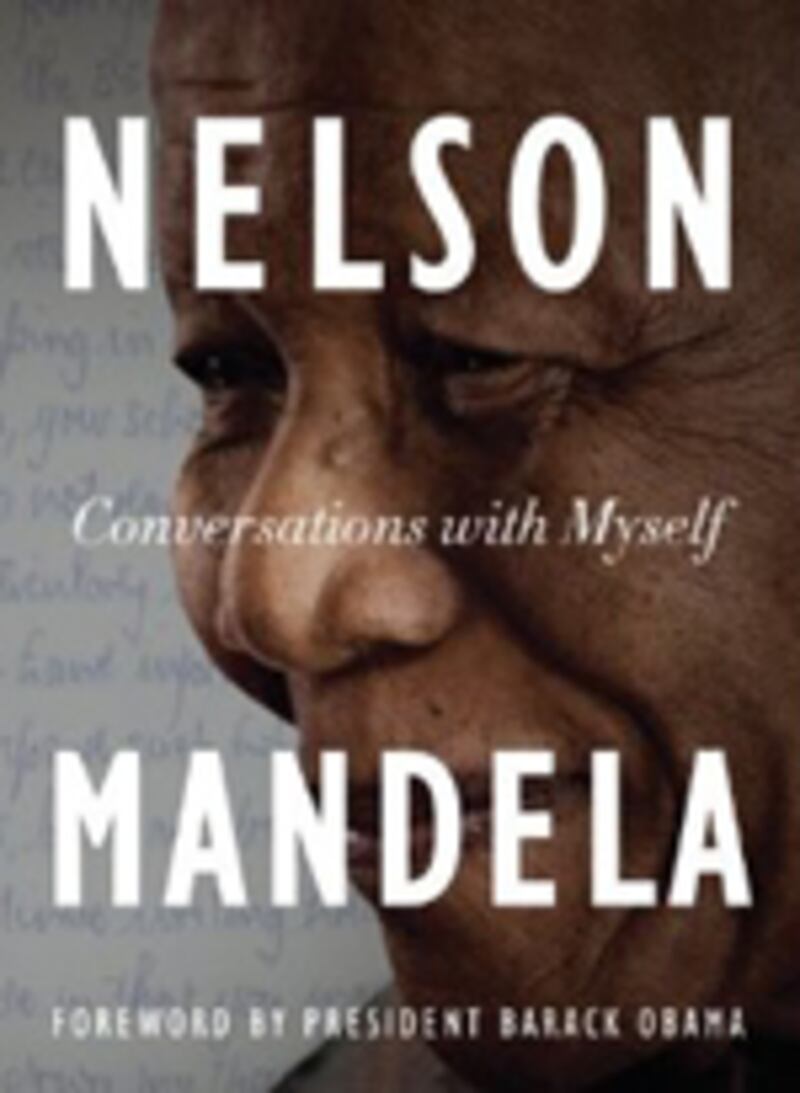

As literature, a famous politician’s story usually comes in three packages: the self-serving memoir; the biography; and the collected papers. Nelson Mandela has the first two, both of the international bestselling variety. His autobiography Long Walk to Freedom (1994) might be the most popular book ever written by an African. His biographies range from the hagiographic (Mary Benson’s in 1980), to the authorized (Fatima Meer’s in 1988) to the really really authorized (Anthony Sampson’s in 1997) to the solid (Martin Meredith’s also in 1997) to the underrated (Tom Lodge’s in 2006) to the gossipy (David James Smith’s just this past June in England—the American edition appears in December).

The collected papers of a statesman is a bit more unusual. Very few get the “Full Jefferson,” as it is known. For 60 years, Princeton has been publishing the third president’s papers. They have just finished volume 36 and are up to the year 1802, with a projected 24 more volumes to go.

Conversations With Myself is not the first Mandela collection. Two compilations of his speeches, letters, and articles were issued in London, one in 1965 and another in 1978, both with subsequent editions. But this promised to be the mother lode. And in a way it is, a tumbling farrago of materials gleaned from Mandela’s personal archive: interviews, conversations, unpublished manuscripts smuggled out of jail, notebooks, diaries, letters, meeting notes, travel journals, jottings on calendars. There are many reproductions of his careful handwriting, often signed “NR Mandela, 466/64” (his prison number). The book leads off with a foreword from President Obama, quite the marketing coup.

Still, it’s disappointing. This is original primary-source material, but it is heavily redacted. Ruth First, in editing that 1965 collection, deleted a paragraph from a 1956 article of Mandela’s that described the benefits of his political movement’s platform for the African middle class—it was deemed too bourgeois. Now a paragraph has bloomed to whole sections of his life. Most of the materials are excerpted. Sometimes it is comical, with a letter being reduced to just a fragmentary sentence or two.

Mandela is not at fault. He had nothing to do with the book. The archivists met with publishers and then approached him, as they wrote in the introduction. “Mandela was briefed and gave his blessing, but indicated his wish not to be involved.”

Not that it would have been more revealing had he edited it himself. Mandela did not want messy personal details in his Long Walk to Freedom, and here his handlers have been just as circumspect. In fact, the richest moments in the book come from a transcription of a conversation Mandela had with Ahmed Kathrada, one of his fellow Robben Island inmates. Kathrada acted as an intermediary between Mandela and the editors at Little, Brown, during the polishing of Long Walk to Freedom. Mandela says that the rough draft, written by Richard Stengel, an American journalist and Time editor, had exaggerated some stories. “The question of dramatizing things, even when they are not correct is a typical American thing,” Mandela informs Kathrada. Then Kathrada brings up another question from Little, Brown, about his engagement to Winnie Mandela. At first Mandela tells Kathrada to report back that he wouldn’t answer the question. Then he says, “Or just say I can’t remember.”

Despite the evasions, the book does contain some interesting revelations.

—The Wise Mandela

Mandela went underground in May 1961 and eluded a massive manhunt for 15 months. When he was finally caught, the South African police tried to plant rumors that Walter Sisulu, one of Mandela’s closest friends, had betrayed him. When Sisulu finally met face-to-face with Mandela (in jail, naturally), he was extremely worried that Mandela had believed it. Mandela calmed Sisulu, telling him he wasn’t fooled. (It turned out the CIA had tipped off the police.)

—The Reluctant Mandela

In an unpublished manuscript written in the late 1990s, Mandela wrote that he had not wanted to stand as president for the 1994 election, preferring to serve the nation without an official position within the government or the African National Congress. When senior ANC leaders insisted he run for president, he agreed but said he would serve for just one term. They replied that the ANC would decide that as well. Mandela, soon after the 1994 election, preempted them by publicly announcing he would step down after one five-year term.

—The Pop-Culture Mandela

One early 1990s reproduction of “his personalized notepaper,” as the caption reads, has Garfield the Cat at the top. This, from a hardened revolutionary, from a man who trained in guerrilla warfare and plotted to overthrow the apartheid regime?

He’s also a big fan of Tracy Chapman.

—The Sexy Mandela

How about this for an odd note: In a 1980 letter to his and Winnie Mandela’s daughter Zindzi, he recalled a salacious memory of Winnie: “She was barely 25 then and looked loving and tasty in her young and smooth body that was covered by a pink silk gown.” Tasty?

—The Wife-Abusing Mandela

Not too many guys who have fled one arranged marriage and been messily divorced twice can still be worldwide icons, but Mandela has retained a saint-like, Morgan Freeman-burnished image in part because until recently not much was publicly known about the end of his first marriage to Evelyn Mase. We knew about Mandela’s adulterous ways while with Evelyn as far back as the 1988 Fatima Meer biography, and in 1990 we learned that Evelyn claimed that he throttled her once. With the new Smith biography, we found out that their 1950s divorce files were filled with accusations of numerous assaults (punches to her face, knocking her down). Mandela has always denied it all, but he now admits that one argument turned violent, saying that Evelyn pulled a hot poker out of a coal stove and tried to burn his face and he twisted her arm until he could take the poker away.

—The Emotional Mandela

The book is full of poignant moments. Letters from the late 1960s brim with pain as he was not allowed out of prison to attend the funerals of either his eldest son or his mother. The book is dedicated to his granddaughter who died in a car accident in June on the eve of the World Cup. But the most powerful, heartbreaking image is from a letter to Winnie Mandela in 1970. Mandela mentioned how he had seen a boat leaving Robben Island, the windswept Alcatraz where he was imprisoned for 18 years, and he knew Winnie was on board after their visit (30 minutes every six months). “As it drifted slowly away with you, I felt all alone in the world and the books that fill my cell, which have kept me company all these years, seemed mute and unresponsive.”

Plus: Check out Book Beast for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

James Zug is the author of The Guardian, a history of South Africa's anti-apartheid newspaper. Run to the Roar, his new book, is forthcoming next month from Penguin.