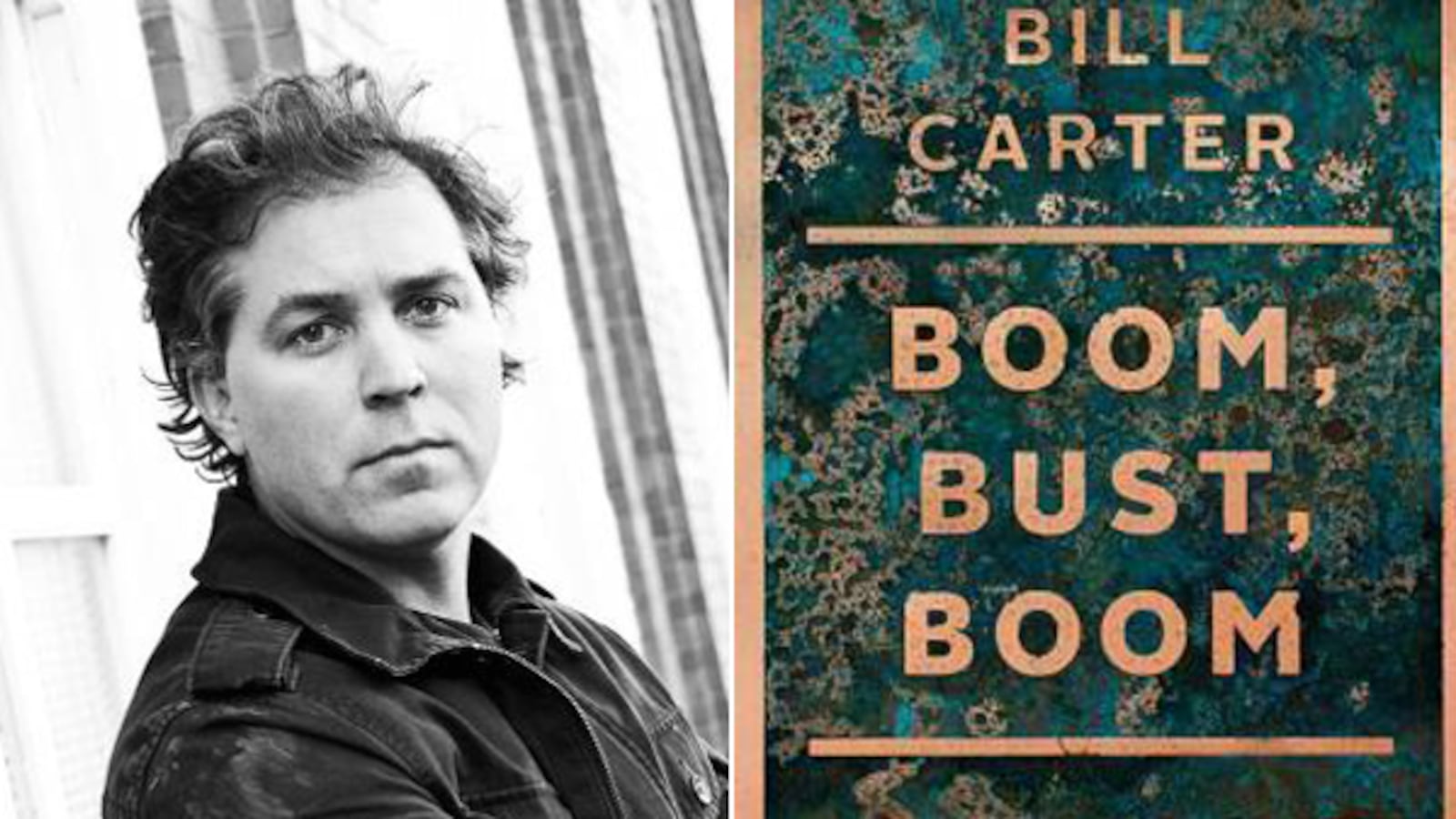

As talk began of reopening the copper mine in Bill Carter’s adopted home of Bisbee, Ariz., the author and filmmaker launched an investigation into the history of the copper-mining industry and its impact—economic, environmental, and otherwise—on communities. His search for answers led him throughout the state, the country, the world, to the doorsteps of miners and moguls, and Boom, Bust, Boom is Carter’s powerful narrative about his pursuit of “the metal that runs the world” and how far we will go to get it. Carter is not a preacher of environmentalism nor a corporate apologist. He just wants to understand.

Why copper? Why this book? Why now?

When my wife and I moved to Bisbee, Ariz., in 2000, we knew it was an old mining town. The Bisbee mine used to be one of the biggest copper pits in the world—at a time when Bisbee itself was the biggest city in between St. Louis and Los Angeles—but the mine closed in 1975, and if you live in a mining town, the open pit is just part of your life, just another landmark you learn to ignore. Bisbee had already become a much different place, attracting lots of eccentric and creative people who wanted to get away from suburbia, so we didn’t quite put it together that Arizona was the third-largest copper belt in the world, producing 60 percent of the copper used in the United States.

I’m a big gardener, so I started tearing up the whole yard, and I got sick. Turns out our soil had really high levels of arsenic, lead, and other heavy metals. I already had a 2-year-old, and my wife was pregnant with our second at the time, so I suddenly became acutely aware of where I lived and whether I wanted to start a family there, especially as talk of reopening the mine began heating up. I started thinking about copper and copper mining and what it means for the communities of people in mining towns.

You write that you can’t avoid copper because it “creeps into your life.” How so?

Copper mining is the most toxic form of metal mining in the United States, but you can only moan and groan about it so much. Once you realize how pervasive copper is, there’s no escaping it. It’s everywhere. Houses, cars, airplanes, computers, cellphones—anything modern with electrical elements has copper in it, but it’s inside, it’s hidden, so you don’t see it or touch it. The average house contains 400 pounds of copper; a 747 uses 135 miles of copper wiring; constructing an eight-story building might require 15 to 20 tons of copper. China builds a new city the size of Chicago every year. Do the math. The amount of copper needed is extraordinary. And that’s all because copper is the perfect metal. It has no substitute. It’s conductive, it’s malleable, it’s cheap, and it doesn’t decay—80 percent of all the copper that’s ever been dug up is still in use, so your dishwasher could have 1,000-year-old copper inside it. It’s so integral to our society that the price of copper often predicts the direction of the world economy. If countries are building, they need copper.

You’ve suggested that copper has a kind of “shadow history,” that its importance in the development of modern civilization is not readily apparent. Can you give us a few examples?

Copper has been driving civilization forever. The Egyptians built a copper water system that still works to this day, but the Romans were the most obvious (and aggressive) example. The Romans learned how to smelt copper into brass, then bronze, to make weapons, and suddenly war was an entirely different game. They invaded Britain to get the copper and tin in Wales. Cyprus had a huge copper mine. Carthage did too. We see those battles in the movies with their loose mythology—as if every battle was about a woman—but usually it was about a spice or a mineral. Copper was a huge reason Rome got so powerful. They had a huge supply of the metals that made war, and it made them unbeatable.

The United States is the other big example. Most people think that gold was the sole driving force of our push into the West, but as gold became the symbol of “striking it rich,” copper quietly developed into a long-term, profitable industry with its own roster of moguls and robber barons. With the advent of electricity in the 1870s, the world fundamentally changed. We needed more copper than we could possibly imagine, and these individuals made huge sums of money.

Who were some of the biggest names in copper and why haven’t I heard of them?

You have. You might know them from elsewhere, but they made their money in copper. William Randolph Hearst was a gold and copper prospector in Montana before moving into publishing. William Clark (whose daughter, Huguette, you might remember, recently passed away) was the single richest man in copper. The Guggenheim family, with their friend J.P. Morgan, ran the copper-smelting game. So much of the wealth of New York City was connected to these guys running around the West. Even today, the biggest copper companies—Freeport McMoRan, Rio Tinto, Grupo Mexico—are all Fortune 500 companies that create staggering personal wealth, but it’s all hidden in corporate shareholders and board members.

As you began to look deeper into the copper industry, what did you learn about the environmental impact of copper mining on surrounding communities?

Acid rock drainage is the single biggest pollutant associated with copper mining. Whenever you expose buried earth to air and water, there’s going to be sulfuric acid runoff on a massive scale. No one knows how to stop it, so it’s going to pollute the local water table. There’s also a lot of air pollutants—silica, dust—that are health risks for people nearby. So the environmental discussion is not just about “destroying a previously pristine landscape.” It’s about water and food. In Anchorage, Alaska, a scientific panel debated the wisdom of opening the Pebble Mine (potentially the largest copper mine in North America) in Bristol Bay, home to the largest sockeye-salmon fishery in the world. It generates $400 million per year in revenue and feeds thousands of people around the world, and there’s a lot of science that says opening the copper mine would destroy the fishery.

So copper is integral to modern society, but copper mining is harmful to the environment. What should we do?

On a very practical level, we need to change the 1872 Mining Law. It allows companies (even foreign companies) to mine federal land for $5 per acre without paying any royalties. That’s insanity in today’s world. On oil and gas, companies pay 8 to 12 percent, but on copper—nothing. Not a dime. There’s no oversight. They can just steal the wealth and walk away, leaving a Superfund site behind them, and no one is liable. People have been trying to change it for decades, but there are just too many vested interests in keeping the law on the books.

That said, we can’t fight against every environmentally bad thing, and I can’t save Bisbee from a mine that’s already there. We need copper to run the world, but we also need a deeper understanding of the tradeoffs we’re making between minerals and the really important things like food and water. The Pebble Mine is the prime example. I think it should be stopped. There’s a lot of places to get copper; we don’t have to destroy ourselves to get it. If we sacrifice the fishery, I don’t know what that says about ourselves.