ROME—When Francesco Bonura was sentenced to 18 years and eight months in prison for mafia collusion and extortion in the early 2000s, anti-mafia investigators cheered. They had finally put the important Sicilian kingpin behind bars.

In the 1980s, Bonura, now 78, was tried for five different murders and a “lupara bianca”—a term used when the body disappears without a trace. He beat those charges on a technicality about the weapon used in the killings, but investigators worked tirelessly to put him away, and eventually they did. During his sentencing trial, the prosecutor called him one of the Sicilian Cosa Nostra’s “most influential bosses,” a “valiant” mobster and trusted ally of the likes of Bernardo Provenzano, one of the deadliest leaders the Sicilian mafia has ever known.

Bonura walked out of prison this week, allowed to serve the rest of his sentence under house arrest because he qualified for “compassionate release” under Italy’s new COVID-19 regulations to get inmates over the age of 70 out of overcrowded prisons if they have health issues.

In normals times, inmates serving time for mafia-related crimes are kept in relative solitary confinement, have visitations and mail monitored and are kept far away from the general prison population so they can’t recruit or direct from their jail cells. The risk in allowing mobsters out of jail early and unsupervised is that they can easily get back to business. Those high in the organized crime hierarchy will automatically garner the respect they had before they went in and will easily rise to cult status now that they are out.

Bonura can only leave his home for medical appointments, but there would be nothing stopping him from communicating with foot soldiers, which is becoming increasingly important now that the mafia has started to fill the vacuum created by the state over the pandemic.

Also released this week was Rocco Santo Filippone, a 72-year-old Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta mobster serving time for instigating a series of deadly attacks against carabinieri officials in 1993 and 1994, killing several officers. He was officially convicted of “mafia-type criminal association, attempted and consummated murder” which were considered aggravated by proof that he was working as a liaison between the Sicilian Cosa Nostra and his home turf ’Ndrangheta. The prosecutor who won the conviction against him wrote a complaint about his release, urging against it because of the ample evidence that the ties he has to both groups “still exist.”

But because of his pre-existing health conditions, he has been allowed to live with his daughter-in-law in Turin (his son is in prison on mafia charges that would undoubtedly make his father proud). Filippone is considered “too frail” to even have to wear an electronic bracelet.

One gangster with a compromised immune system was let go even though he’s not even 70. Vincenzino Iannazzo, 65, was serving a lengthy sentence for crimes he committed allegedly running one of the ’Ndrangheta’s clans in the Calabrian town of Lamezia, where he returned this week. His defense team successfully argued that because he was serving his term in Spoleto, which has a high number of cases, he was at particular risk.

Italy’s anti-mafia directorate is understandably displeased by the compassionate release measure, which was meant to release other types of criminals, such as those serving time for white collar or non-violent crimes. But once those inmates were released, the prisons were still overflowing, so more had to be let go to allow prisoners to live in single-occupancy cells to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. There are now 74 known mob bosses with health conditions that will qualify them for early release. They are all serving under the so-called 41-Bis penal code, which is meant to prohibit anyone convicted of mafia collusion from being granted early release or parole.

There are many other incarcerated mafia thugs who are deliberately trying to break the rules of social distancing as an attempt to get sprung. “It is a very alarming situation,” Leo Beneduci, secretary general of Italy’s largest prison police officers’ union, told the Guardian this week. “In Italy there are approximately 12,000 members of criminal organizations in prison. Members of the penitentiary police have begun reporting detainees who embrace each other with the alleged goal of increasing the possibility of contracting the virus and getting released from prison.”

Italian anti-mafia magistrate Antonino Di Matteo who heads the National Anti-Mafia Directorate accused the state of forming a “pact with bosses and institutions” akin to the Clean Hands scandal of the 1990s when 5,000 public figures and 400 businesses were investigated for mafia collusion. He called the release of mafia bosses “a further serious offense to the memory of the victims and to the daily commitment of many humble servants of the state. The state seems to have forever forgotten the season of massacres. The state is giving the impression of having bowed to the logic of blackmail that had inspired the riots.”

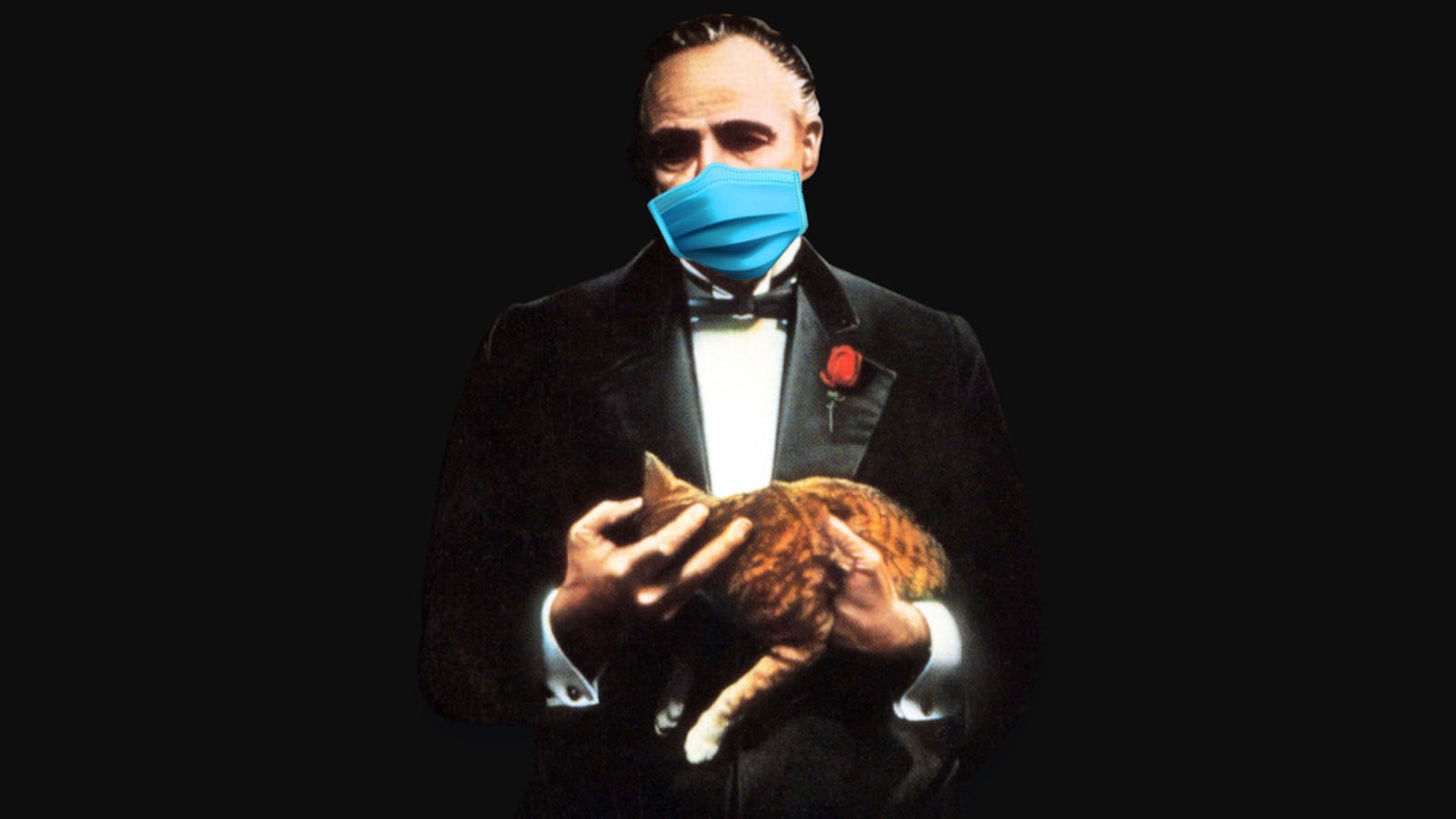

Lirio Abbate, the editor of L’Espresso weekly magazine who lives under police protection for his anti-mob journalism, warns of something worse. In an exposé this week, he wrote that release of important mafia figures coupled with evidence that organized crime syndicates are already lending money and helping provide essential services to the poorest in the country is a recipe for disaster. “The risk is that we’ll find the mafia virus on the streets alongside COVID-19,” he said. “It would be a double pandemic that we mustn’t allow to happen.”