George Floyd’s girlfriend broke down in tears on the stand Thursday as she told jurors about her three-year relationship with the 46-year-old “mama’s boy” who loved his children, food, and exercise—but struggled with a “life-long addiction” to opioids, like so many Americans.

“Floyd liked to work out every single day, lifting weights. He did sit-ups, push-ups, pull-ups, just within his house. He would go biking…he loved playing neighborhood sports with kids,” Courteney Ross, 45, testified in a Hennepin County courthouse. “He was the type of person who would run to the store.”

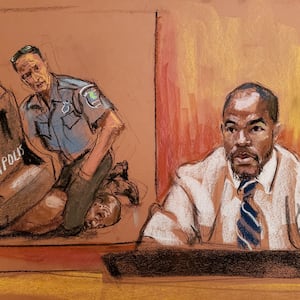

Ross is one of several witnesses who have testified so far against former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin—who is on trial for second and third-degree murder as well as second-degree manslaughter after holding his knee on Floyd’s neck for over nine minutes during an arrest over a counterfeit bill.

Three other officers—Tuo Thao, Thomas K. Lane, and J. Alexander Kueng—have pleaded not guilty to aiding and abetting second-degree murder while committing a felony, as well as aiding and abetting second-degree manslaughter with culpable negligence.

Chauvin’s defense lawyer, Eric Nelson, has argued that Floyd’s death was the result of health issues and drugs—and that his client was simply doing what “he was trained to do throughout his 19-year career.” Through Ross’ testimony, prosecutors sought to address that narrative head-on, painting a sympathetic portrait of Floyd and his long-term battle with opioid addiction.

Her voice breaking, Ross described how she first met Floyd in August 2017 when she went to see her son’s father at a Harbor Lights Salvation Army shelter where Floyd worked as a security guard. After “fussin” in a corner of the lobby, she said Floyd “came to her” and asked her “sis, you ok?” and if he could pray with her.

“Floyd had this great deep southern voice. Raspy. And he’s like, ‘Sis, you OK, sis?’ And I wasn't OK. I said, ‘No, I’m just waiting for my son’s father. Sorry.’ He said, ‘Well, can I pray with you?’ I was so tired. We had been through so much, my sons and I. And this kind person, just to come up to me and say can I pray with you, when I felt alone in this lobby. It was so sweet,” Ross said. They talked for a while and shared their “first kiss in the lobby,” she added.

Together, they explored the Twin Cities, often going to a sculpture garden and out to dinner, Ross testified. At the time, Floyd worked security at the Conga Latin Bistro until the pandemic forced its closure.

“Floyd was new to the city, so everything was new to him, made me feel like I was new to my own city,” Ross said, adding that they always had “an adventure” together. She added that Floyd would often talk about his children, whom he “loved.”

But after his mother died in 2018, Ross said that Floyd became “kind of a shell of himself, like he was kind of broken.”

“He didn’t have the same bounce that he had. He was devastated. He loved his mom so much. He talked about her all the time. I knew how he felt. It’s so hard to lose a parent that you love like that,” Ross said, describing him as a “mama’s boy.”

That tragedy was among several triggers in Floyd’s ongoing struggle with opioid addiction, which began with prescription drugs to address chronic pain. Ross said the pair both tried to break their addictions many times throughout their three-year relationship but it became “a life-long struggle.”

“Both Floyd and I, our story—it’s a classic story of how many people get addicted to opioids. We both suffered from chronic pain,” she said. “Mine was in my neck and his was in his back. We both have prescriptions. We got addicted, and tried really hard to break that addiction many times.”

Ross added that there were periods of time when they both stopped taking the powerful drugs, and others when they used pills they purchased on the street. One of those relapses occurred in March 2020, and around that same time, Floyd tested positive for COVID-19 and had to quarantine with some of his roommates.

During cross-examination, Ross admitted Floyd was hospitalized in March for an overdose, saying that after she picked him up for work one night he complained about not feeling well—and she knew something was wrong.

“He wasn’t feeling good. His stomach really hurt. He was doubled over in pain,” Ross said. She took him straight to the ER but had to leave to get to work and still does not know what caused the overdose, she testified.

Ross told the court she suspected Floyd was using again in May. The last time she spoke with Floyd was on May 24, when the couple spoke over the phone. He told her he was spending the night with some friends.

One of those friends, Morries Lester Hall, filed a notice Wednesday night stating that he plans to exercise his Fifth Amendment rights—meaning he will likely not testify during the trial.

On May 25, Floyd was arrested after allegedly using a fake $20 bill at Cup Foods. Hall, who Ross acknowledged sometimes provided the pair with drugs, was in the passenger seat of Floyd’s car during the arrest. Ross also admitted Wednesday that she overheard a conversation in May that led her to believe the 46-year-old bought pills from Hall.

Christopher Martin, the 19-year-old cashier of the convenience store, testified on Wednesday he almost accepted the $20 bill Floyd used to buy cigarettes—but decided to tell his manager to avoid a docked paycheck. “If I would have just not taken the bill, this could have been avoided,” Martin told the court.

Several bystanders testified on Monday and Tuesday, they repeatedly asked Chauvin to remove his knee and to check Floyd’s pulse during the arrest. Among the group were an off-duty Minneapolis firefighter and EMT, who was ignored when she repeatedly offered her assistance, and an MMA fighter who tried to explain that Chauvin’s chokehold was cutting off Floyd’s circulation.

When paramedics finally arrived at the scene, Chauvin had to be instructed to get off Floyd. Prosecutors state that when Floyd was loaded into the ambulance, he had no pulse.

Seth Bravinder, a paramedic with Hennepin EMS who responded to Floyd’s arrest, told jurors on Thursday the initial call said Floyd had suffered a mouth injury and was not deemed an emergency. About a minute later, he said the situation was “upgraded” and they rushed to the scene to find “multiple officers on the side of the road with our patient laying on the ground next to a squad car.”

Bravinder added he “didn’t see any breathing or movement” from Floyd, prompting his partner, Derek Smith, to check his pulse and conclude he had gone into cardiac arrest, meaning his heart had stopped. Smith told the court on Thursday that Floyd’s pupils were “large” and based on his overall condition he thought the man “was dead.”

As officers and paramedics loaded Floyd onto a stretcher, Bravinder said that he “was limp... he was unresponsive and wasn’t holding his head up or anything like that.”

He added that because they were surrounded by “upset” bystanders—which can be “taxing” for paramedics who need “mental power and focus”—the pair drove a few blocks away from the scene before attempting to resuscitate him.

But by the time they began that process, Bravinder said, the cardiac monitor showed that Floyd had “flatlined,” and his heart wasn’t pumping blood. Smith told the jury that paramedics performed numerous measures inside the ambulance to try to save Floyd, including shocking him, but he remained “in a quote-unquote dead state.”

“[H]e’s a human being and I was trying to give him a second chance at life,” Smith said. He then slammed the Minneapolis police officers for not starting chest compressions at the scene.

Jeremy Norton, a captain with the Minneapolis Fire Department, testified Thursday that he joined paramedics in trying to stabilize Floyd as he was brought to a local hospital. Afterward, Norton reported Floyd’s death internally because he “was aware that a man had been killed in police custody.”

Retired Sgt. David Pleoger, a former shift supervisor with the Minneapolis Police Department who received a call about the arrest from a concerned 911 dispatcher, said Thursday that Chauvin didn’t initially tell him he’d kneeled on Floyd.

“I believe he told me that they had tried to put Mr. Floyd... into the car. He had become combative,” Pleoger said. “I think he mentioned that he had injured—either his nose or his mouth, a bloody lip, I think, and eventually after struggling with him, he suffered a medical emergency and an ambulance was called and they headed out of the scene.”

It wasn’t until they were at the hospital, where Floyd was hooked up to medical machines, that Chauvin said he’d used force on the man’s neck, but he didn’t say for how long.

The Hennepin County Medical Examiner concluded Floyd died of cardiac arrest from the restraint and neck compression, also noting that Floyd had heart disease and fentanyl in his system. An independent report commissioned by Floyd’s family, which will not be shown at trial, concluded that he died of strangulation from the pressure to his back and neck. Both reports determined Floyd’s death was a homicide.