Editor's note: Jeffrey Epstein was arrested in New York on July 6, 2019, and faced federal charges of sex trafficking and conspiracy to commit sex trafficking. On August 10, 2019, he died in an apparent jailhouse suicide. For more information, see The Daily Beast's reporting here.

The story of Jeffrey Epstein—a bizarre, self-described billionaire who bought his way out of trouble after police uncovered a sexual assault ring operating from his Florida mansion—has fascinated the public for over a decade. So it makes sense that best-selling uber-rich crime writer James Patterson is, like the rest of us, obsessed with the mystery of his Palm Beach neighbor.

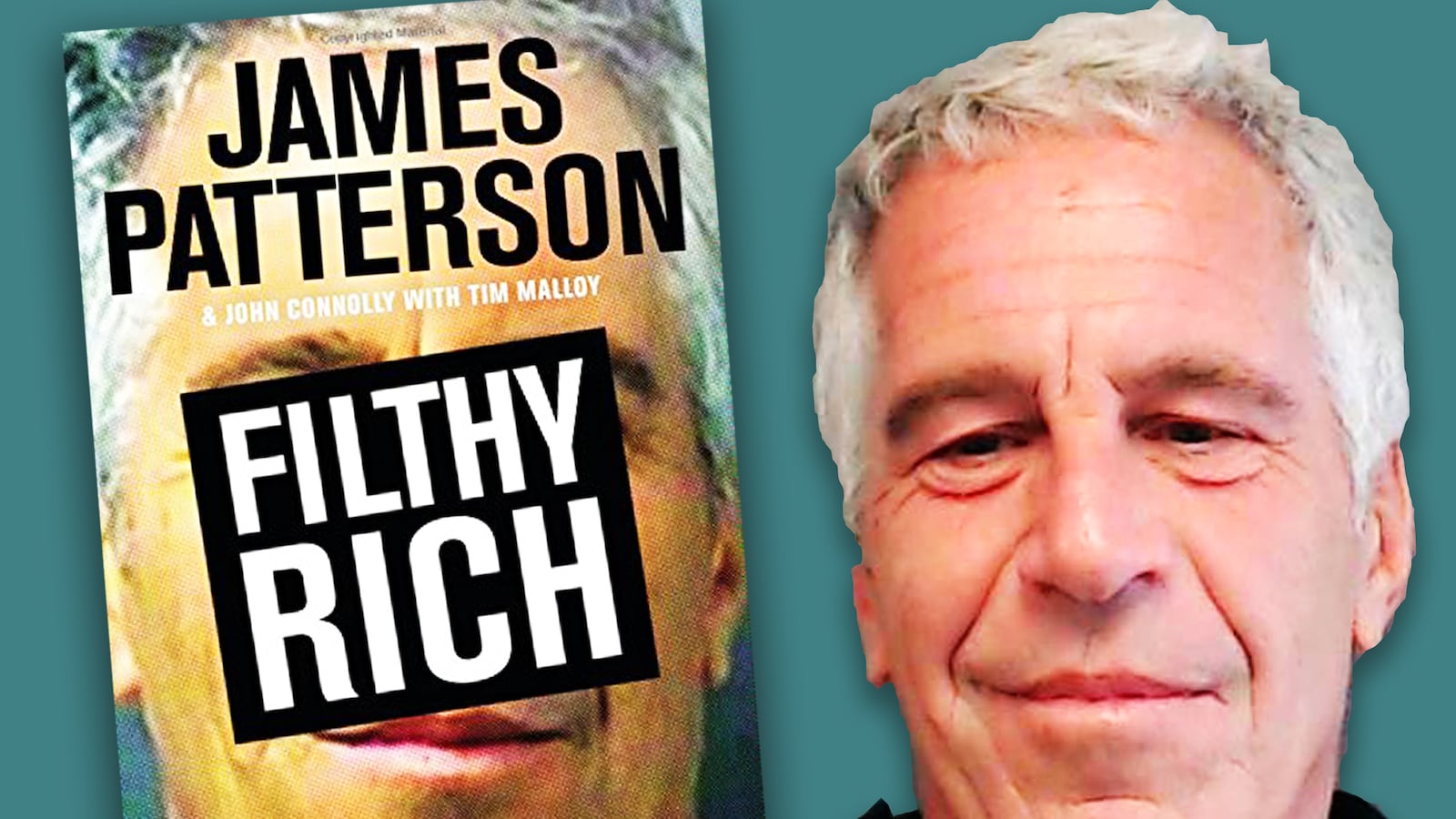

And so, Patterson, the 69-year-old book mill owner and operator who holds the record for most No. 1 New York Times best sellers, has taken a rare swoop into nonfiction territory to give us Filthy Rich: The Shocking True Story of Jeffrey Epstein. As with most Patterson novels, Epstein’s tale is co-written—a generous characterization of the situation where Patterson employs dozens of ghostwriters and publishes their work under his brand—with John Connolly, a former New York police detective, Vanity Fair editor, and current Florida private eye, who (it has been rumored) at one time allegedly worked for the Church of Scientology.

Indeed, what is already known of Epstein, the massage-loving Icarus who flew too close to underage girls, is shocking. Dozens of profiles, hundreds of reported pieces, and thousands of pages of court documents have told the story of the man who worked for and socialized with New York’s wealthiest and most famous while surrounding himself with loyalists who either actively aided in his sexual assaults of postpubescent girls or kept his secrets.

Sadly, Filthy Rich has little to add to the canon.

Patterson’s 287-page book is organized into tiny—sometimes just single-page—chapters, bearing the subject’s name and a date. These early, smaller chapters are meant to create scenes in the lives of the victims, but provide less detail than one might get by googling. These tableaux show girls between 14 and 18, getting ready to meet Epstein, dodging their parents’ concerns, and conversations between them and the high-school classmate who acted as one of Epstein’s madams, luring girls to the mansion’s massage room. (Patterson writes in his author’s note that scenes and dialogue have been “recreated.”)

As detailed in the book, citing news reports covering the constellation of court cases that have spawned from his crimes, Epstein between the years 1998 and 2007 ran a kind of depraved pyramid scheme, paying young girls $200 (or more if they would “do more”) to give him sexual massages, and recruiting them to bring other young girls into the fold. These messages—which would occur up to three times a day, with different girls each time—were just a way to get high-school girls through the door, however. Once inside his room, a naked Epstein would grab them, masturbate, and sometimes penetrate them with his fingers, a vibrator, or his oddly-shaped penis, according to the girls.

Strangely, Epstein’s penis is the rare instance where the book is large on details. Lingering on his anatomy in several sections—calling it “egg-shaped,” “very tiny,” “some sort of birth defect,” “like a teardrop, like a drop of water ... really fat at the bottom and skinny at the top where it’s attached. And it never gets fully hard, ever.”

When police got wind of Epstein’s activities, they launched an investigation that led to a 53-page indictment. If convicted, Epstein was facing decades in prison, but he needn’t worry: A team of powerful and talented attorneys that included Alan Dershowitz and former Clinton special prosecutor Kenneth Starr launched an aggressive—and ultimately successful—campaign to discredit the prosecutors as well as the young victims. (Epstein recruited vulnerable girls from the wrong side of the tracks who were less likely to tell anyone about the assaults in exchange for modest sums of money and perks like car rentals and movie tickets, the book notes.)

U.S. Attorney Alex Acosta claimed the state didn’t stand a chance against Epstein’s legal dream team. “Our judgment in this case, based on the evidence known at the time, was that it was better to have a billionaire serve time in jail, register as a sex offender, and pay his victims restitution than risk a trial with a reduced likelihood of success,” he wrote in a 2011 letter, which Filthy Rich quotes in full.

In the end, Epstein would strike a slap-on-the-wrist deal with prosecutors that enraged local police. He’d pay settlements to dozens of accusers, but plead guilty to only one count of soliciting a minor. He served 13 months of an 18-month sentence in a Palm Beach county jail—16 hours of which every day but Sunday, he could spend at his home or in his office, due to a work release provision in the deal.

The book’s best chapters are its longer ones—but these are often just printed depositions, letters, police interviews, and court documents. News stories are quoted from liberally. Vicky Ward’s profile for Vanity Fair, as well as her explanation in The Daily Beast for why the most incriminating pieces were removed by her then-editor Graydon Carter, are among the published pieces examined at length.

In Part II, “The Man,” Patterson examines Epstein before his fall.

The 63-year-old was born to and raised by middle-class parents in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. A math whiz, Epstein was soon teaching at the Dalton School, a prestigious private prep school on New York’s Upper East Side. Through a parent at the school, Epstein parlayed the position into another, better-paying one at Bears Stearns where he worked on tax issues for ultra-wealthy clients. But he didn’t stay long; Epstein resigned during an insider trading investigation of Bear Stearns by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. From there, he collected rich clients, including the founder of The Limited Inc., Leslie Wexner, who some say gifted Epstein New York’s largest private residence. Exactly what he did for them is unknown. Maybe he had ties to the government? Maybe he fashioned tax shelters for his clients? If Patterson knows, he’s not telling.

Through philanthropy, Epstein opened his circle to academics and political giants—Nobel Prize winners, Stephen Hawking, and Bill Clinton are all counted as friends who visited Epstein’s private island in the Virgin Islands. Patterson uncovers no evidence that any were involved with Epstein’s criminal activity. And despite tabloid headlines, Filthy Rich, has nothing new on Epstein’s ties to Donald Trump, or Bill Clinton.

The original reporting is limited to brief interviews, including law enforcement officials; old Brooklyn friends who said Epstein always seemed like a nice Jewish boy to them; a former acquaintance who said Epstein used to lie about having money (he allegedly stole her friend’s Concorde jacket and would tell people he flew on the aircraft, “a total lie,”); and Todd Meister, Nicky Hilton's ex-husband who knows Epstein through his mega-rich dad and dishes in the book that Epstein (whom he calls a “yutz”) once bragged that he “liked to go into insane asylums because he liked to fuck crazy women.”

They also interviewed Anna Salter—a clinical psychologist (and, it goes unsaid, mystery novelist)—who has never met Epstein, but makes a few general statements about narcissism and psychopathy.

In almost every section of Filthy Rich, Patterson asks the reader questions—seemingly the same ones forming in his readers’ minds.

“Who is Jeffrey Epstein?” “How Did Jeffrey Epstein make all his money?” “Is Epstein a born psychopath?” “What exactly was he guilty of?”

Filthy Rich, one could assume, was a failed attempt to answer these questions.

“I thought it was a really powerful story, and I thought it needed to be told,” Patterson recently told The Wall Street Journal.

If only somebody would.