“Witness the real Cuba here!”

Writer Pedro Juan Gutiérrez is exclaiming on his eighth-floor rooftop terrace, while pointing at the surrounding ruins of Central Havana—mansions that once exuded luxury and that now offer a full view of the heavens from their stripped frames. From this same terrace in the ’90s, Gutiérrez saw people push small boats into the Caribbean in the hopes of crossing over to Miami, only 370 kilometers away. “Desperate, often drunk, people stumbled into an ocean full of sharks to meet their death,” he says.

There is no such thing as el periodo especial in the Cuban press, that time when the Soviet-Union fell apart and Cuba lost its Communist Sugar Daddy. While novelists painted island idylls in baroque words and journalists acted as propaganda machinery of the Castros, Gutiérrez spat the despair and the struggle for survival of the pitch-black ’90s onto paper. “There was no drinking water, no food, no gas for cooking. The garbage was not picked up because there was no petrol. My apartment began to collapse like so many of the houses here.”

In his novels, Gutiérrez’s semi-autobiographical character, Pedro Juan, hustles through his days—always looking for some pesos in legally dubious ways, and greedily relishing sex, rum, cigars and marijuana. Pedro Juan reflects the townspeople he sees every day. “Material poverty generates moral poverty. Survival requires creativity.”

His Trilogia Sucia de la Habana (1998) about the “special period” was published in 23 countries, yet even today, it remains forbidden in Cuba. The newspaper for which Gutiérrez worked promptly threw him out after he published his work.

Gutiérrez, now 66, was 9 when Fidel and Raul Castro ousted dictator Fulgencio Batista from the presidential palace in 1959. In the ’60s and ’70s he saw the revolution become part of the Cuban identity. “My generation fought for a political project that we found important, for cultural and human goals rather than material gain. Everyone enjoyed education. There was censorship, but music, literature, film and visual arts were being brought to the people.”

Then disillusionment followed. The young generation that was told in the ’90s that everything would soon get better is now nearing 50 and still survives on an average of 20 dollars per month. Their children can no longer be convinced.

“The revolution has disappeared from the minds,” says Gutiérrez. “Young people are apolitical. They focus on their own problems and projects rather than collectively mobilizing for a greater responsibility. Their goals are materialistic in nature.”

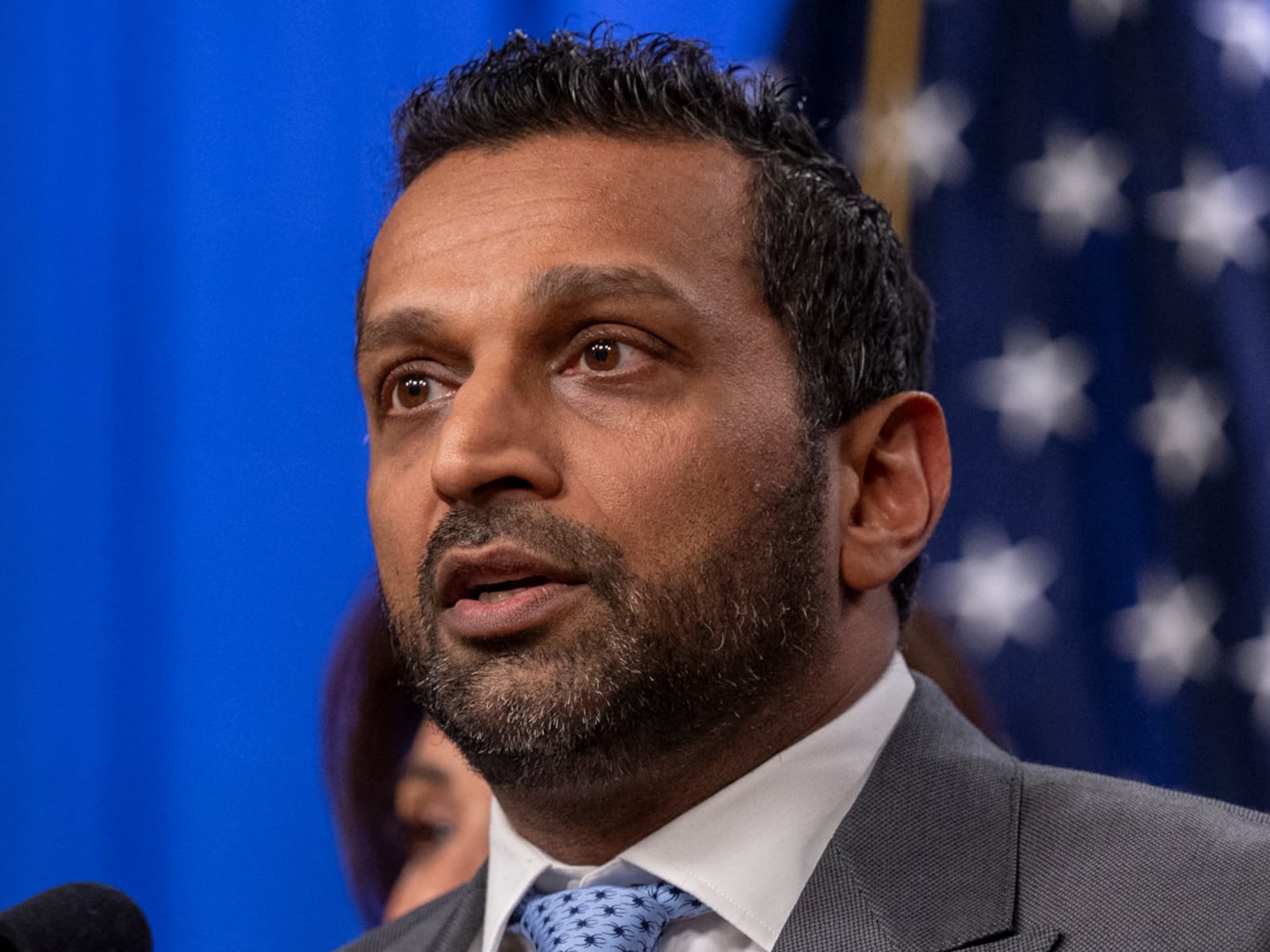

Cuba’s Double Brain-Drain

According to journalist Carlos Manuel Alvarez Rodriguez, his generation—born around 1990—is completely disconnected from the people in power. “Every day the government doctrine continues to disintegrate. We talk to foreign tourists, we view illegal television channels, we get information via the paquete [hard drives with foreign films, series, music and web pages that are spread over the island weekly]. We now know through a thousand channels that the Cuban press sells us lies. Young Cubans are tired of the talk that is talked, with no walk being walked. They take their lives into their own hands.”

Hundreds of Cubans crowd the Embassy of Panama these days. Hastily they copy the recently relaxed visa rules that hang on signs outside of the closed iron gate. Through Panama they hope to reach the U.S. Annually, some 30,000 Cubans receive residence visas, without the hurdles that other migrants have to pursue. In addition, in 2014 an estimated 20,000 Cubans illegally made their way over to the archenemy.

In 2015 this number increased by 77 percent. It shows the skepticism with which the Cubans have welcomed the diplomatic thaw announced by Obama and Raul Castro at the end of 2014. Despite trade restrictions easing, these people are trying to reach the U.S. before the Cuban privilege would die on a green card. Since December, Cuban doctors are required to ask governmental permission for a trip abroad again, a measure that had been abolished in 2013. Where most of the immigrants were once family members of Cubans in Miami, now mainly they are young professionals try to reach the U.S. At a pace of 50,000 immigrants, Cuba loses 1 percent of its active population every year—not a gift for the already ailing economy.

Teens and tweens who remain in the country no longer opt for a university education. Why would they? An engineer, architect, or surgeon earns 20 to 60 euros per month. So they go work in a tourist resort or as a taxi driver, jobs that earn you more money as a cuentapropista or an independent worker. The double brain drain is one of the biggest threats to the growth that Castro envisions with his timid reforms.

Alvarez knows that Cubans gradually gain more freedoms, but it’s all too slow. “The government will continue to take arbitrary decisions and believe that those decisions are in the interest of the people. The ball of reforms does not start rolling by government initiative, but by Cubans trying to make something of their lives in creative ways. The rulers simply legalize what the people have been doing for years.”

Similarly, Alvarez tries to push against the acceptable limits. One of the platforms he writes for is the online magazine OnCuba. He writes about things for which Gutiérrez lost his job in 1997. “Ten years ago this was impossible, but I dare not say that I am completely free of self-censorship. You can fight your built-in censor, but it does not turn off. In a Cuban publication, I cannot frontally attack Fidel Castro. But I do that in foreign media to clear my conscience.”

Alvarez is aware that very few people in Cuba are reading articles online. Homes rarely have Internet access. Only since last year, there have been Wi-Fi hotspots in Havana and few other cities. An hour of surfing costs two dollars, one-tenth of the average monthly wage. “Whoever can afford surfing goes online to talk with relatives abroad, not to sit and read an online newspaper,” Alvarez acknowledges. Critical political awareness is barely there after decades of dictatorship. “Do not believe that the Cubans are waiting on democracy. Above all, they want to lead a better material life.”

Still, Alvarez also has much to say regarding sacred cows such as education and health. “The quality of the achievements of the revolution has been deteriorating for decades and the government does nothing to stem the tide. We are told that our health is much better than those in other developing countries. That’s right, the infant mortality rate is even lower than in the U.S. But we do not compete with Haiti. Only with the health and education we had 10 years ago. Our economy is a disaster and we have no liberties. On the countryside, all you see is poverty. If, additionally, the only achievements we have made start to worsen, what is left for the Cubans?”

A Long Journey

In the rural Pinar del Rio, in the far west of Cuba, Nirma Carrasco and her 10-year-old son, Cristian, are gearing up for the long trip to Havana. Cristian has a heart condition and will undergo an operation in a metropolitan hospital. It is the fifth time they will travel there in a truck with people packed inside like cattle, because the bus is too expensive.

Carrasco's husband, 36-year-old Noidan Alonzo, has never been to the capital. Once again, he has to watch his wife and child travel alone. Behind the house, a mountain of smoke escapes from the burning charcoal. “It keeps smoldering for four days. All this time, I cannot sleep because I need to tend to it every half-hour. This morning, before sunrise, suddenly the flame flew inside of it,” said Alonzo, while he sharply shovels the earth onto the mountain of smoke.

He is obligated to sell the charcoal to the government for 5 Cuban pesos (18 U.S. cents) per bag. Consider it his contribution to the revolution, despite politics being the last thing to keep Alonzo awake at night. Havana reigns far from his bed. Obama? Never heard of him. He does know all about avocados, beans, and manioc.

Nonetheless, he has reason to worry. For 80 percent of Cuba lives off of imported food, accounting for $2 billion per year. Much of it now comes from the southern United States. If American farms and food companies would be given a free hand to sell in Cuba, the unproductive local agriculture would be pushed out before re-sowing time.

The periodo especial forced the Cuban farmers to return to the most traditional form of organic farming. “We had no pesticides. The Russian agricultural machinery no longer worked because there were no spare parts or fuel. We did not even have any working animals. From sowing to harvesting, everything was done by hand,” Alonzo says.

Raul Castro, more pragmatic than his brother Fidel, knew he had to reform the highly inefficient agricultural sector. He invested in organic and urban agriculture, giving farmers the right to cultivate more than 1 million hectares of unused farmland and more freedom to choose what they grew on it. In addition to his duties as a charcoal supplier, Alonzo has beans, rice, fruits, coffee, cows, and some sheep to meet the basic needs of his family. It has to do. Alonzo estimated his family income to be roughly 1,000 Cuban pesos ($37 U.S. dollars) per year. “And the book of food stamps is getting thinner. In addition, the yogurt we buy with the stamps is repulsive.”

The countryside guajiros survive primarily through solidarity. “The bull and the goat of the neighbor come fertilize my beasts for free. I lend my horse out, another lends out his car. And at night we patrol together to protect our livestock from thieves.”

Several months ago Alonzo joined forces with 20 other farmers in a cooperative to which he is able to sell agricultural products for his own account. “That is an improvement. It provides extra pesos.”

Poor Europe

In Minas de Matahambre, another 15 kilometers on, Luis Hernandez has joined the cooperative that buys Alonzo’s harvest. He opened a fruit and vegetable stall on the languid main street of the village. “If we get new opportunities, I am always the first to jump on the bandwagon,” Hernandez says, laughing with infectious entrepreneurial enthusiasm. To him, it’s his way to be a leader of the revolution. “I want to set up projects. If I could, I would feed the whole village.”

Hernandez worked in the copper mine after which the village takes its name, until it closed its doors in 1997. Many of his fellow villagers went on their way. He then tried to be independent, but the many government restrictions played tricks on him. “The restrictions have been largely eliminated. I now earn much more than before. I am glad that the new president dares to bring about change. Revolution means progress, not a standstill.”

“Next, the U.S. trade embargo has to be lifted,” Hernandez notes. “It hurt Cuba. A lot.” In rural areas of Pinar del Rio, the public discourse sounds much stronger than it does in the capital. There is no Internet, no sign of foreigners. Hernandez feels sorry for the Europeans. Daily, he sees on state television how mercilessly the refugee crisis hits Europe. He believes they are better off here.

On the countryside, the CDR’s (local Committees for the Defense of the Revolution), still dominate. With the notorious actos the repudio, presumed opponents of the revolution, such as human-rights defenders, are assaulted with intimidation and violence.

According to the Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation (CCDHRN) in January no less than 1,414 political arrests were made. Remarkable, given that President Obama had set more respect for human rights as a condition for visiting the country. Cuban state media are already seeing the president’s visit as an American acknowledgment that the country indeed respects human rights.

Hernandez may admire the CDR as much as he likes—“Nothing happens without them knowing it. Therefore, there is no crime here”—but he, too, lowers his voice consistently and glances around when he announces anything sensitive. But is this not the way it has always been?

Hernandez and his wife, Miriam Leon, see golden times ahead. Only recently they have been able to take out a loan at the bank and sell their home on the private market. They are happy and wish to stay in Minas. But they realize that their children see it differently.

The 23-year-old Luis Isaac is an independent hairdresser, who surpasses the local standards of an average wage. “Ten pesos (37 U.S. cents) per haircut is more than many workers here earn in a day,” said Leon. “In addition, I also give him the income of a room we rent out. If we help him build a good life here, hopefully he will not leave.”

The 16-year-old Larissa—all bony cheekbones, dark eyes, bleached tresses—hopes to follow her brother’s footsteps. “In Minas my peers all aim to become a doctor, but I see that a barber earns much more.” For her 16th birthday, the whole family traveled to the Varadero tourist resort. Never before had they seen consumer products such as sunscreen. “It tasted like more,” she smiles. “I can’t say I don’t long for other places.”

The Serial Mistress

For 27-year-old Mireille, it was clear as day on her 18th birthday that she would not stay in Cuba. “Everyone wants to get away from this rotten island.” Like her sister, Mireille married a rich, older Italian.

And so it goes—more girls seek the arms of fortunate foreigners to provide them with a future. The revolution had banned prostitution, but in the ’90s they began to inch back due to a lack of alternatives. “Even the whores have a university degree in Cuba,” Fidel Castro once said. Where there are large groups of tourists, the jiniteras today inevitably swarm around them. Depending on their goals, they are either looking for a few drinks, money for sexual services, or a one-way ticket abroad.

Mireille went straight for the main prize. She moved to Italy, served her marital duties for several years, and divorced again. With an Italian passport to fall back on, she began working in an elite nightclub in Milan as a companion girl, earning at least 5,000 euros per month. When a drug addict scion from a wealthy family gave her three blank checks last year, she cashed €300,000 and bought a mansion in Vedado, Havana’s old residential area.

“It’s an investment. I’m not returning to Cuba. I am only here to witness the renovation,” Mireille says. Downstairs, her impressive new home is still a construction site, but her room already has an oversized Jacuzzi. On the roof she shows where the pool and bar will be placed.

The Cuban government does not tolerate any great earners, and jiniteras even less. Without pressing benevolent tips into the hands of the appropriate police, the girls risk many years in prison. But are they not only doing what father Cuba has always taught them? Cuba has always been a jinitera, to the U.S. the Soviet Union, Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela; in exchange for living and spending money, the successive sugar uncles received an attractive conquest to flaunt to their rivals.

“I know I’ll be written off in a few years,” Mireille admits. “I am preparing for that moment, by investing in real estate, among other things.” Cuba, by contrast, has never prospected such a way up. Cuba never held the idea of standing on its own feet. When Hugo Chavez showered his petrodollars onto his ideological ally, any and all necessary reforms immediately fell quiet again. That is how Cuba fell into heavy times again following his death.

After 50 years, the political parties are starting to realize what Mireille already knew at age 20: You better not place your future in the hands of one Sugar Daddy. And so Cuba talks to Europe, Brazil, Mexico, and the IMF while openly flirting with China and Vietnam. The rapprochement between Cuba the U.S. should be seen in that context. The year 2016 is not the year of Obama in Cuba, but the year in which a suffocating serial monogamy paves the way for functional polygamy. Cuba’s prostitutes learned from the master, and lately the elderly revolutionaries are starting to follow their way.

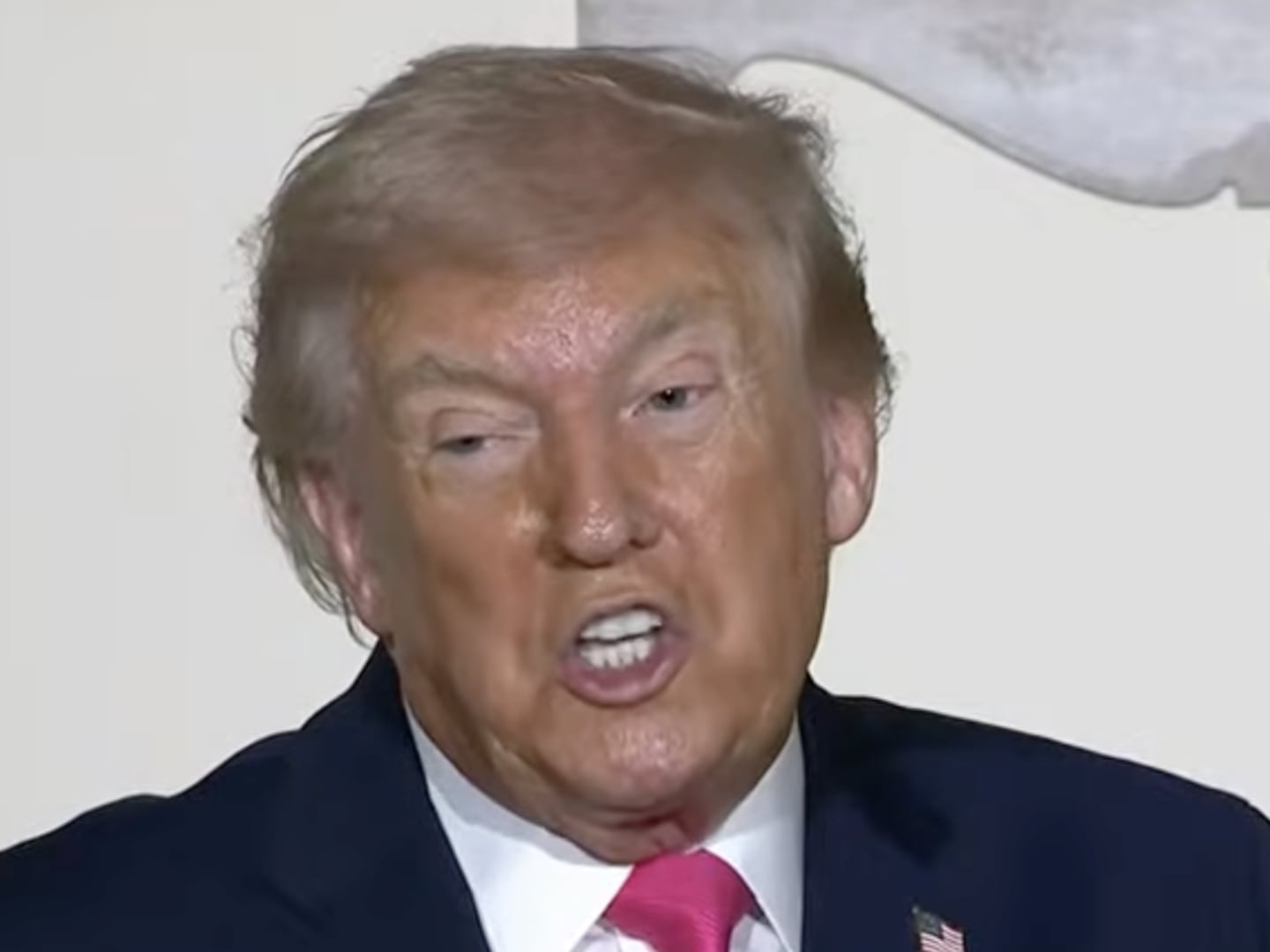

Obama In Cuba

The visit from Barack Obama is not a radical change, but the next step in the normalization of Cuban-American relations—a process that has been going on for several years behind the scenes.

The Republican majority in Congress still refuses to lift the ban, but Obama has put considerable strain on trade restrictions within his presidential powers. American tourists in Cuba don’t fear persecution, even though traveling to Cuba, with some exceptions, remains illegal. Both countries are working on a ferry, float air and direct mail delivery. U.S. telecom companies sucked in contracts to get one of the least of connected countries in the world online and out from its isolation.

The radical Cuban anti-Castrists are slowly dying out and are becoming less and less of a political factor. Presidential candidates Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz—both with Cuban roots— criticize Obama’s visit, but the odds are small that they would tighten the embargo in their presidency. The American business world is too keen on trading opportunities in the backyard for that to ever happen again.

On March 21, Obama and Castro will likely announce new business deals, but floating on the surface remains the rhetoric of human rights. Obama calls for more freedom for ordinary citizens. Leading up to the historic visit, Cuba has freed dozens of political prisoners.

Obama must and will speak with dissidents, but Cuba will identify which dissidents those will be. Both presidents will be dancing on a tightrope, as the Cubans have been for decades.

Jan De Deken is a foreign correspondent whose work has taken him to the Earth's four corners. In between tracking down in depth stories on international events he's writing a book on the world's happiest and unhappiest places, which comes out fall 2016. You can follow him on Twitter @JanDeDeken.