Assemblywoman Yuh-Line Niou first came to Albany as a staffer to Ron Kim, the only Korean American member of New York state’s legislature.

“We were alone up there. Alone,” she recalls, describing the setting for the harassment she faced: having her body groped by legislators, being told she and her boss would make a “hot duo” and should have sex, and being sized up for a “hot or not list.”

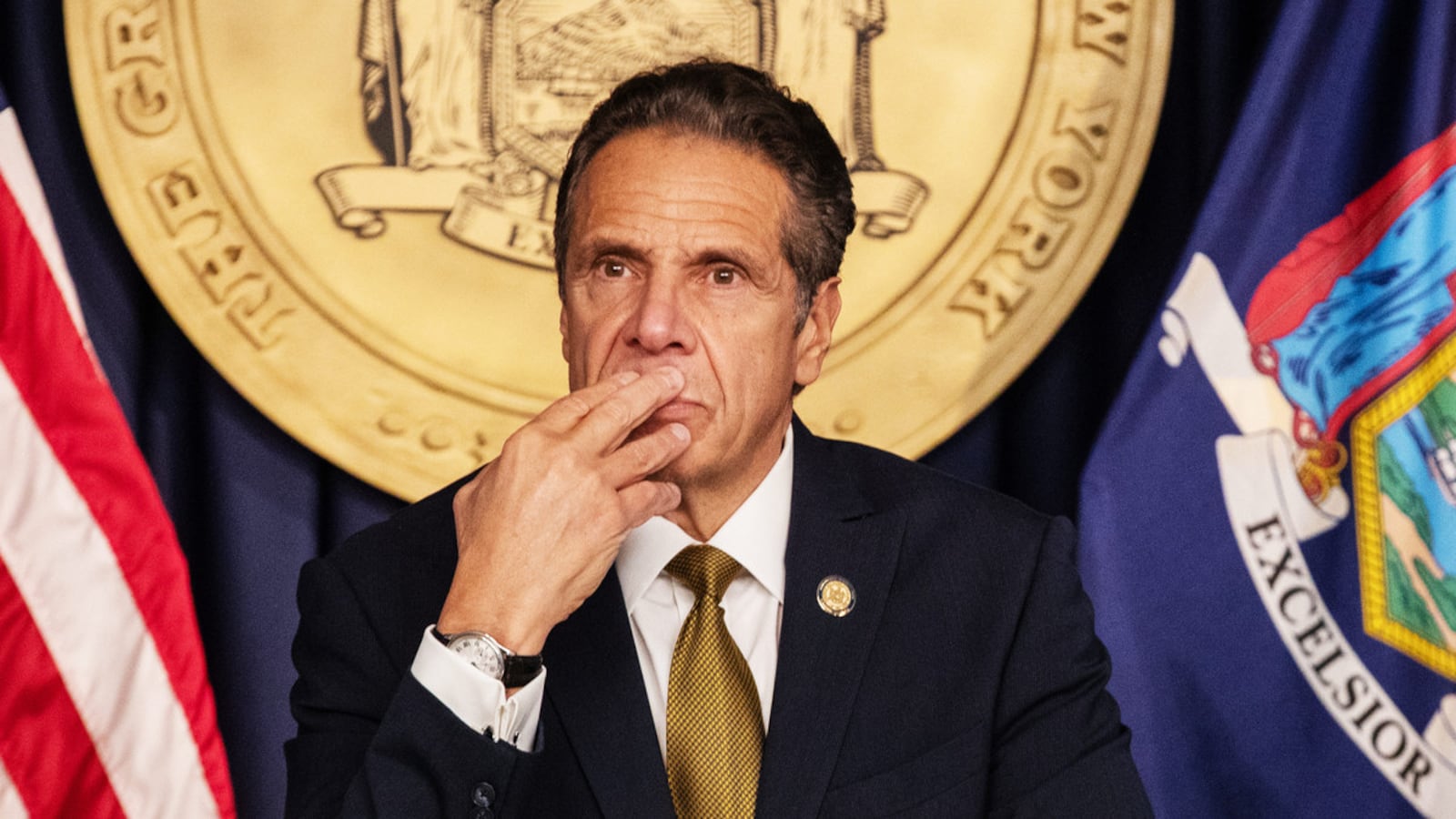

Niou, who is Taiwanese American and who won her own seat in 2016, has been heralded as one of a group of young female legislators challenging the culture of the state capitol that’s been defined for decades by corruption and sexual predation. Now, that group has been taking aim at a fellow Democrat in New York’s three-term governor, Andrew Cuomo, after three women—former executive chamber staffers Lindsey Boylan and Charlotte Bennet, and Anna Ruch, a guest at a wedding at which Cuomo officiated—have come out with detailed accounts of their harassment by him in the last week.

While Las Vegas used to advertise “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas,” New York State legislators have been (slightly) less open about the Bear Mountain Compact, a long-standing agreement between mostly male lawmakers that anything that happens in Albany—and often involves interns or young staffers—is not to be mentioned back home.

Harassment in Albany is casual, expected, and, more often than not, tolerated. Interns are regularly advised by female legislators not to fraternize with legislators or powerful aides. They are warned that these men are accustomed to getting what they want.

The harassment extends up the chain. It’s so casual and accepted in Albany that a 2016 interview between this reporter and powerful budget chair Liz Krueger about sexual harassment reforms was interrupted by a Republican senator who massaged her shoulders and called her “Lizzy Baby.”

Reminded of that incident this week, Krueger, who was 59 years old when the incident occurred, explained why she had shaken it off so easily; in some ways it had been a cost of doing business. She noted that that specific senator would physically tease her, “You know, like an elementary-school kid putting your pigtails in an inkwell sort of way.” She confronted the senator, who reportedly responded, “I do this to people I really like!”

“We’re not children. I hope we can get past this. You could just tell me that you find me entertaining and smart,” Krueger says she retorted.

A similar situation with another senator did not end so calmly. This man tended to get angry after heated floor debates and return to the lobby to drink. He often berated women, but this time, Krueger says, he launched into an obscene sexual tirade directed at her. “Some of the stuff was so inappropriate. But I’m not easily shaken,” says Krueger. “I told him if I thought you could spell any of those words then I’d be offended.” A group of male senators surged forward to stand between the two. “I wasn’t worried he would hit me,” Krueger recalled. “I’m a senator, I’m protected. But it sure seemed like his colleagues thought he might.”

That was the culture in Albany when a teenaged Andrew lived with and worked for his father Mario, then the lieutenant governor. It’s still largely the culture there now as a sexagenarian Andrew, in his own third term as governor to match his father’s total, presides over a capitol where the Bear Mountain Compact is finally being challenged by staffers and interns willing to speak out about their mistreatment and a new generation of Democrat lawmakers, including many women, finally standing behind them. It’s been a long road there, with many bumps including:

In 2001, Elizabeth Crothers, an Assembly aide, accused then-Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver’s aide Michael Boxley of rape. She recalled recounting her ordeal to Silver while he callously munched on pretzels. He took no action against Boxley. His inaction came back to bite him in 2003 when Boxley was accused of another rape and pleaded guilty to a lesser misdemeanor for sexual misconduct.

Despite that, Silver maintained his control over the Assembly for another decade and a half, serving as one of the “three men in a room” who controlled Albany along with Andrew Cuomo until the speaker surrendered to the FBI on corruption charges in 2015.

In 2006, as Cuomo was running for state attorney general, Assemblyman Ryan Karben resigned after being accused of watching porn with three interns at his Albany home. In 2007, Assemblyman Mike Cole was censured for sleeping over at the home of his 21-year-old intern. He lost re-election the next year. In 2008, the Assembly’s ethics body cleared Greg Ball of harassment of a former staffer. He later won a seat in the Senate and in 2010 was accused of groping a waitress.

Also in 2008, Eliot Spitzer, who had earned the nickname “the sheriff of Wall Street” in his years as state attorney general, resigned just 13 months after being elected governor when it came out that he had regularly patronized prostitutes and after a separate investigation by then-Attorney General Cuomo had seriously damaged his political position.

Upon taking the reins from Spitzer, Governor David Paterson and his wife both admitted to extra-marital affairs, seemingly in an effort to protect themselves from scandal amid tales of Paterson’s drug use and partying. And yet in 2010 The New York Times reported that Paterson had used his influence to threaten a woman who was allegedly assaulted by his close aide David Johnson. Paterson quickly faced pressure to resign from the Democratic establishment and Cuomo launched an investigation from his position as attorney general. Paterson eventually announced he would not seek re-election, paving the way for Cuomo’s long-rumored run.

Also in 2008, the Assembly found that member Sam Hoyt had had an inappropriate relationship with an intern. In 2011 he joined the Cuomo administration. He resigned in 2017 in the midst of a sexual harassment investigation, having settled a lawsuit with a woman he had an affair with for $50,000.

In 2009 and 2011 Assemblyman Micah Kellner was accused separately by a female and a male aide of harassment. An Assembly ethics investigation found the complaints valid in 2013. Kellner objected to the findings but did not run for re-election.

In 2012, multiple female staffers accused powerful Assemblyman and Brooklyn boss Vito Lopez of using gifts to try to win sexual favors, inappropriate touching, and demanding flirty emails he could use to deny any accusations. Lopez resigned in 2013, after Cuomo and other political leaders demanded he do so.

In 2014, Assemblyman Dennis Gabryszak resigned after seven women filed suits in state and federal court alleging harassment. The state ethics board investigated and found a pattern of sexual misconduct.

In 2015, then-Senator Jeff Klein was accused of forcibly kissing staffer Erica Vladimer during a staff celebration at a bar. Klein, who made himself into the “fourth man” in the room and helped Cuomo maintain Republican control of the Senate through his leadership of the so-called Independent Democratic Conference, faced calls for his resignation and an investigation from Albany’s deeply dysfunctional and corrupted ethics board. Klein lost re-election to Sen. Alessandra Biaggi before the investigation concluded. Biaggi, a former Cuomo staffer, has said on social media that she saw troubling behavior from the executive branch in her time there and is one of the Democrats now calling on Cuomo to resign.

In 2017, the Assembly banned former Assemblyman Steve McLaughlin from having interns, following an investigation that found he solicited nude pictures from a staffer.

In 2018, Eric Schneiderman, elected attorney general when Cuomo was elected governor, resigned after four women accused him of physical assault.

And now Cuomo himself stands accused of harassment of women who worked for him. Niou says that the meetings of the Democrat caucus have become painful as the accusations have mounted and as some male colleagues openly talk about wanting to move on and get to “the real work,” and as Cuomo has pretty openly pointed to the budget due at the end of the month as a reason to move on for now from the claims piling up against him.

Sexual harassment was the focus of reforms in Albany over the last decade thanks to the Sexual Harassment Working Group. Members of the group include survivors like Elizabeth Crothers, who accused prominent Assembly aide Michael Boxley of rape; and Rita Pasarell, Leah Hebert, and Tori Burhans Kelly, who worked for Brooklyn Assemblyman Vito Lopez, whose litany of harassment claims included that he’d demanded staffers feel his tumors, paid them to dress more sexily, forced them to send him flirty text messages, and tried to stay in hotel rooms with them.

In 2019, the Sexual Harassment Working Group finally forced the issue into the spotlight as the legislature held a powerful day-long hearing on sexual harassment, the first in Albany since one in 1992 under Gov. Mario Cuomo.

In 2020 Committee on Open Government head Robert Freeman, whose job was to help reporters secure information from the state, was accused of pressuring female reporters for physical contact and flirtation in return for his help. Fifteen people, including reporters, testified to the Inspector General about Freeman’s behavior, with one of them testifying that he’d been "squeezing her shoulder, putting his arm on her waist, touching her buttocks with his hand, placing her braids behind her shoulder, hugging her, and kissing her during this work meeting,”

And also in 2020, Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who in 2014 founded New York’s Women’s Equality Party as a cynical way to fend off a primary challenge from a woman and who’s never met with the members of the Sexual Harassment Working Group, signed a harassment law he falsely called the strongest in the nation.

A little more than a year after that, Cuomo himself was accused of harassment and of having people in his orbit retaliate against one accuser, Lindsey Boylan, by circulating her personnel files.

Asked by reporters on Wednesday, in his first appearance since the accusations emerged, if he’d taken the sexual harassment training mandated by the law he signed, Cuomo said that the “short answer is yes.”

If that’s so, either the training is no good or the governor is no good, or both.

It’s good that women are coming forward now, says Vladimer, “but the fact that we still have staffers being told they can’t go out for lunch so that they aren’t harassed shows that things haven’t changed much.”

Cuomo, meanwhile, insisted at his press conference on Wednesday that he “never touched anyone inappropriately” and that kissing people hello and goodbye is his “custom.”

“I understand that sensitivities have changed and behavior has changed. I get it. I will learn from it,” the 63-year-old said.

Count Vladimer and Niou among the skeptics. “It's gaslighting,” Vladimer said just after the governor’s carefully stage-managed press conference. “It's gaslighting, plain and simple.”