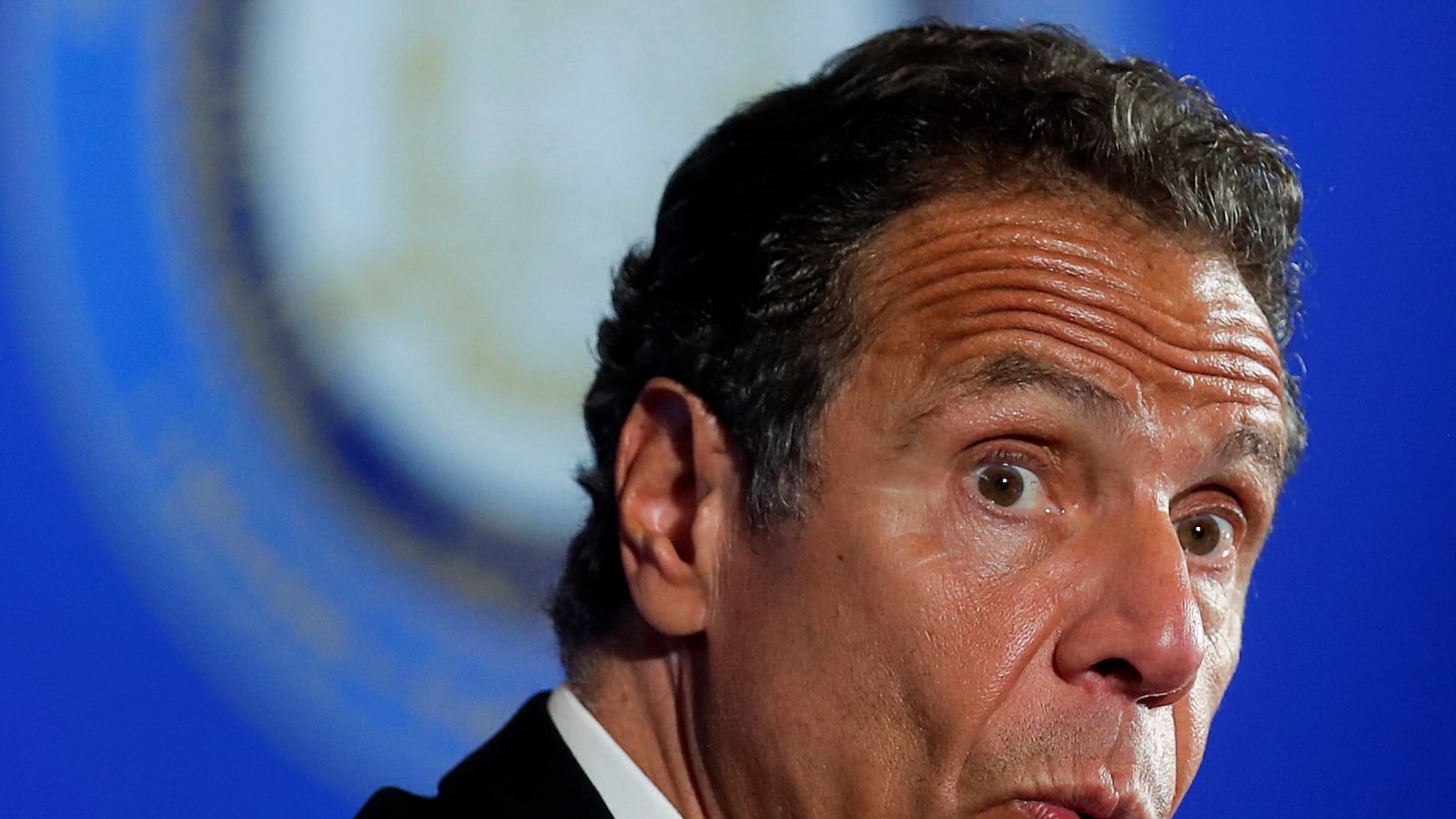

As the daughter of a father, my stomach crawled up into my throat when I read Charlotte Bennett’s account of her time working for Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Bennett is not only the same age as Cuomo’s daughters, she actually told him that in middle school she’d played sports against them. And yet, Cuomo found it appropriate—and, he says, mentorly!—to repeatedly interrogate her about her sex life, talk to her about his physical loneliness since his split from his longtime girlfriend, and advise her to get a tattoo on her butt.

I specify that these feelings come up for me as the daughter of a father because men so often think it’s relevant to frame their concern for women in the context of their familial ties. Cuomo also benefited last year from situating himself as New York State’s dad-in-chief. Just a month before Cuomo’s behavior toward her became aggressively unprofessional, according to Bennett, Cuomo was giving his Emmy-winning little sitcom performance about his daughter’s boyfriend and “natural defiance syndrome.” The summer of Cuomosexuality takes sure seems different looking back.

After what Bennett described, I sincerely hope that no one is taking fatherhood lessons from Andrew Cuomo. I am nearly a decade older than Bennett, and if any of my friends’ fathers spoke to me the way he spoke to her, I would not see that friend’s father again unless he had an open-casket funeral.

I specify our age difference because I am stunned by Bennett’s bravery. Her story is all the more believable because there are no benefits to what she has just done. Already, the internet is raining down a storm of vitriol on her. At only 25, she accepted a fate in which this allegation will forever be linked to her name. Any internet search of her will bring this up, again and again. No one does this lightly, and every man who has witnessed Cuomo’s behavior and said nothing ought to be burning with shame right now.

Bennett’s story is all the more believable because we’ve heard it before. It’s got all the moves from the Albany harassment best-practices playbook. Perhaps most galling is the way Cuomo—the not-the-Onion founder of the Women’s Equality Party!—got creepily, aggressively interested in her past sexual assault experience. “The way he was repeating, ‘You were raped and abused and attacked and assaulted and betrayed,’ over and over again while looking me directly in the eyes was something out of a horror movie. It was like he was testing me,” she texted a male colleague after one meeting with the governor. Vito Lopez, infamously the scourge of Albany, did the same with at least one of his victims, Leah Hebert. Hebert believes these power-mongers target those who have been abused in the past because they’re counting on being able to use that to discredit their victim.

And it’s believable because I’ve experienced it myself. Not from a mentor; I’ve had and continue to have a number of male mentors and not one of them has grilled me on my sexual preferences or talked to me about needing a hug—and not the kind you have with your parents, as Cuomo stressed to Bennett while dragging her into a conversation about how long it had been since he’d really hugged someone.

I experienced it at the hands of another man employed in Albany. In 2019, I was named in an article about Robert Freeman, the once powerful state employee who’d led the committee on open government since 1976 and who the Cuomo administration delightedly took down when it came out that he had been inappropriate with a number of women in professional contexts. I was one of those women. Two years prior to his exposure and ouster, I’d written about my worst encounter with him without naming him.

When I read Bennett’s account of her conversations with the governor, I was suddenly reminded of Freeman. I unfortunately think about Freeman a fair amount, much more than I’d like. I finally went on the record about my experience with Freeman in part because of the suffocating guilt I felt when I woke up one morning to learn that a 23-year-old reporter had been harassed by him in a way that was startlingly similar to my own experience. Even if I knew intellectually that the only person responsible for Freeman’s behavior was him, I felt like it was my fault that this young woman had been mistreated. I felt that if I’d taken his behavior more seriously, seen it for what it was—an indication of a pattern—she might have been spared. But I’d assumed it was my fault, that he’d only behaved that way because I had been unprofessional or provocative in some way. Like many women before me, I took responsibility for a man’s bad acts long before he ever even considered doing so.

I was terrified to go on the record, to be on the other side of a story. It felt like I was doing something unprofessional as a reporter, abandoning my duty to stay on my side of the page. But then there was my duty as a person to that 23-year-old reporter, to not let her have to stand alone, to have at least a fraction of the temerity that she did in coming forward to begin with. My options seemed to be: potentially ruin my career, or forever know that I not only allowed this young woman to be violated but that I didn’t even have the guts to stand beside her.

I chose the one that felt less unbearable, I guess. It never really felt like a choice. That’s the thing with these situations: It never does. There’s no point at which we feel powerful, or even a little bit in control. When someone undermines you in this way, no matter what you do, you’re always left feeling like everything you do is just a reaction to the ways in which they messed you up.

I stopped wearing red lipstick because Freeman commented on that so often. It was a small little visual signature I had. I don’t wear a lot of makeup, but after a particularly nasty and confidence-salting experience, I’d tried on a bright red in an airport and felt suddenly powerful, felt like I could be someone I wanted to be again. It meant a lot to me. Freeman turned it into something that felt insidious, that felt like a way in which whatever mistreatment I experienced was invited by me, was my fault. So I stopped wearing it, and tried as best as I could to fade into whatever background I ever found myself in front of.

He would sometimes try to ask me about relationships, like Bennett says Cuomo did. I would brush him off or try to redirect, exactly as Bennett describes doing. Sometimes my attempts at redirection made things worse. When she recounted how she mentioned a tattoo she was considering, and Cuomo then advised her to get it on her butt, I hoped that she hadn’t blamed herself in that moment, like I knew I would have.

People are going to say a lot of nasty things to Bennett. They’re going to tell her the same things I preemptively told myself. I hope that she always knows that none of those things are true, that nothing that happened was her fault, and that all of it mattered and was unacceptable.

Someone asked me why Cuomo didn’t deny Bennett’s allegations, after he put out a statement categorically denying those made days earlier by Lindsey Boylan, who his staff then demeaned on background calls. I speculated that the optics of treating an unknown 25-year-old the same way they did an older married woman with political aspirations were obviously different. But mostly I think Cuomo is counting on people to be okay with him treating a young woman this way. I think he assumes that no one is going to care that a hardworking person was objectified, uncomfortable and had to change jobs because he couldn’t behave professionally. I’m guessing he thinks people will believe that this kind of behavior constitutes “mentoring,” or at least act like they believe that.

It doesn’t. And frankly, he and his staff know it.

I’ve written before about the period of time when Cuomo eagerly bragged about making New York’s sexual harassment laws the “strongest” and “most comprehensive” in the nation. “We are doing everything in our power to crack down on sexual harassment and ensure inappropriate workplace conduct is addressed swiftly and appropriately,” he said then. His right hand, Melissa DeRosa, declared that New York was listening to women “bravely stepping up and speaking out about sexual harassment and abuse” and vowed that the state would “take direct aim at the culture of secrecy, dominance and power inequality that allowed sexual harassment to thrive.”

Secrecy, dominance and power inequality. What a stunningly apt description of what we’re hearing now about the Cuomo administration.

I suppose now we will have a chance to see just how strong and comprehensive those laws really are. Of course, first we’ll have to replace the judge Cuomo picked on Saturday to investigate himself, who unsurprisingly has professional ties to Cuomo’s ally of three decades, and also was the choice of the Catholic archdiocese when they decided to allow themselves to be investigated in 2018.

But many others are breaking with the governor to demand a truly independent investigation. The brave survivors of abuse in Albany, whom Cuomo has steadfastly ignored for years, are among those calling for “Attorney General Letitia James to immediately appoint a Special Assistant Attorney General.”

It’s time to listen to the people who know best. That’s not Andrew Cuomo—not as a mentor, or a governor, or a father.