In the middle of a Saturday night in the spring of 1959, a phone rang on a quiet suburban block in Chevy Chase, Maryland. John Greaney mumbled an apology to his pregnant wife and reached for the nightstand. The clipped voice on the other end said that an “OpIm” had just come in and, after giving a few details, promptly hung up. Greaney sat on the edge of his bed in his pajamas, wondering just what in God's name was going on.

Unknown to his neighbors, John Greaney was not the gray-faced government functionary he appeared to be. He was in fact the deputy chief of a small unit at the CIA known as the Tibet Task Force. It sounded dashing, but in fact the work of the five or six men that comprised the unit was so lacking in excitement that Greaney compared it to running an import-export firm. All the action was down the hall, where the Latin American group would soon be planning the Bay of Pigs invasion.

But beginning that Saturday, Tibet—through the story of the Dalai Lama 's great escape—was about to become famous.

The OpIm message—short for Operation Immediate, the second-highest category of urgency at the agency—came from a CIA-trained guerrilla in the desolate back-country of southern Tibet. Over that weekend, a series of messages from this guerrilla would make it clear that the Dalai Lama had fled from his summer palace in the capital of Lhasa and was heading for the Indian border. His people were in revolt behind him, fighting against better-armed and trained Chinese soldiers. In the next 17 days, thousands would die, tens of thousands would follow their spiritual leader to India, and Tibet as a global cause would be born.

Before that weekend, Tibet had been a beguiling, but complete, enigma to the world. Greaney still remembers the time John Foster Dulles, secretary of State under President Eisenhower, interrupted a briefing Greaney was giving him on Tibet to ask him a simple question: Where, exactly, is Tibet? Dulles, who made Tibet policy as much as anyone did, had no idea where the place was. Greaney had to climb up on Dulles' leather couch to point out the relevant blotch of color on a National Geographic map hanging on Dulles' wall.

The Tibetans who left achieved a kind of freedom. But they lost their Tibet, and in exchange the rest of the world got a small piece of it.

And in fact, as he drove to the CIA's Signal Center in the middle of the night to get the message from Tibet, Greaney, who knew more about the country than 99.99 percent of the American population, had to admit he had no idea what was happening inside the country either.

What was happening was that two revolutions, one personal and one political, were unfolding simultaneously.

The personal had to do with the Dalai Lama himself. For many years, until the age of 15 or 16, His Holiness was not religious at all. Or spiritual. He cared more about war games than he did the Buddha. He had a ferocious temper, growing so angry at times his body shook as he stood on the shiny floor of his winter palace in Lhasa. Religious studies bored him so much he would make up adventure stories about the people in them.

That had all changed at the same time the Chinese invaded in 1950. The Tibetans, who mistrusted the aristocrats and bureaucrats who ruled them, looked to His Holiness in their time of need. Their country was divided and at times verging on civil war, and the Dalai Lama was the only thing that could possibly save them.

Isolated from his loved ones, deeply lonely, poorly educated, the young lama had no idea how to be a leader. And so he turned to Buddhism, not as the reincarnation of a holy line who is finally taking up his destiny, but as a frightened young man searching frantically for a compass. Not only did he find Buddhism, but he also dove deep into its lessons and emerged a different man, who is very much the person we know today, a monk who has given himself over to Buddhism utterly.

As he fled with a small group of relatives across the moonscape of southern Tibet, guarded by hardened Tibetan guerrillas known as the Chushi Gangdrug, the Dalai Lama was not only fleeing the increasing oppression and brutality of the Chinese, he was fleeing the cage of Tibet itself. Before the escape, he lived a life of less-than-splendid isolation. In his two palaces, one for summer and one for winter, every moment of the Dalai Lama's life was scripted and formalized. He was barely allowed to think or speak for himself. And it was sacrilege for his followers to look him in the eye or touch him.

As much as he loved his homeland, the freedom he found beginning on the rough trail to India allowed the Dalai Lama to remake the institution in his own image. He was the 14th reincarnation of the line of lamas and rulers, but his predecessors would hardly have recognized themselves in this compassionate and warmly approachable man. He shed the oppressive weight of tradition as one would slip out of a badly fitting coat, and the process began in those high Himalayan passes.

The second, political revolution was the Chinese snuffing out of the idea of Tibetan sovereignty once and for all. And the birth of the effort to free Tibet that still goes on today.

As the Dalai Lama's escape progressed, the story made headlines and TV news worldwide. “Will he make it out alive?” was the question all of them asked. Tibet became famous as it disappeared from the world map, with even President Eisenhower following His Holiness' progress by sticking pins into a map. John Greaney and his tiny group of men were suddenly the hottest unit at the CIA.

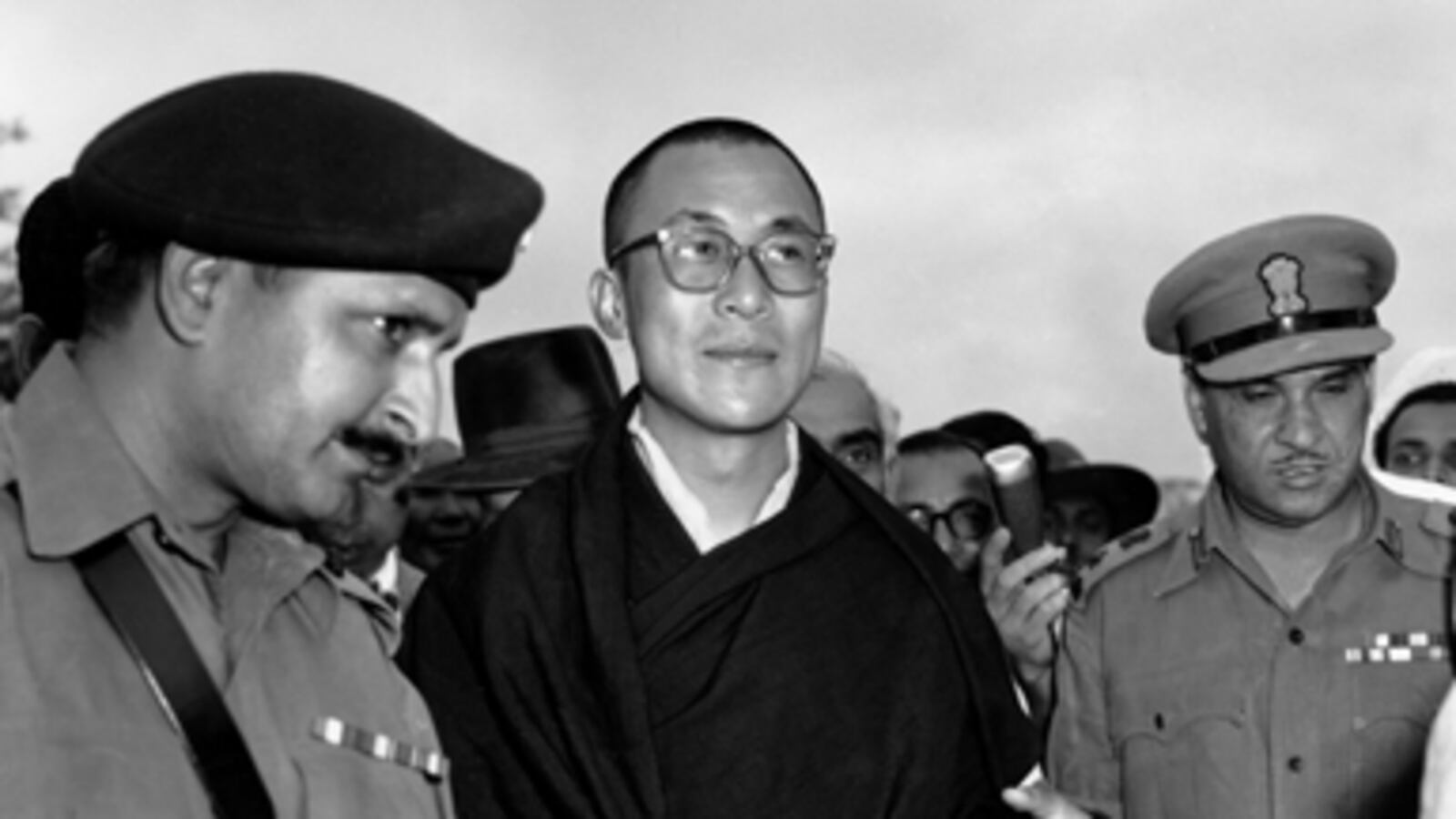

At last, 17 days after he left his summer palace, His Holiness, seriously ill with dysentery, crossed the Indian border. He was free. And Tibet had entered the modern conversation. The escape had changed Tibet utterly. Today, the Dalai Lama's face and basic outlines of his cause are famous throughout the world. And tens of thousands are dedicated to getting dignity and autonomy for its people.

But in some ways all the attention changed nothing. Some 80,000 refugees followed His Holiness into India. And they are still there. I met some of them in the tiny, bare apartments that the Indian government has provided them in places like Dharamsala, the halls smelling strongly of the rancid butter tea that the older Tibetans drink from the moment they wake up. In their eighties now and frail, they are the soldiers, the lamas, and the mothers who brought their families out because they couldn't bear to live apart from His Holiness. They're free now, in a manner of speaking, and the Dalai Lama lives only a stone's throw away.

But ask them about Tibet and they will hold their hands in front of their faces and gasp through their tears. They'll trace the shape of the hills they grew up near and tell you stories of how sweet life was before the Chinese came. Probably it was a hard, rural life with small joys and many frustrations and time and distance have burnished it more than it deserves. But they cry unreservedly. And these are not soft people, not at all.

What the refugees got in exchange for their suffering was the knowledge that the Dalai Lama has made them known to the world, and made the Dharma known. And that Tibet, which was for centuries a hidden kingdom and which today no longer even officially exists, is in a sense, everywhere.

John Greaney and the few surviving members of his task force can be proud of the role they played in the Tibetan diaspora. It was Greaney who sent the cable to Prime Minister Nehru's office in New Delhi, seeking permission for the escape party to cross the border. The fact that the whole adventure happened on a quiet weekend in D.C. was a stroke of luck. If the State Department had been open for business, everything might have played out differently. “If it hadn't been a Saturday night,” the retired Greaney told me, “the Dalai Lama might still be in Tibet.”

The CIA would support the Tibetan rebels secretly for years, until everything changed in 1971 with Nixon's visit to China. The rapprochement meant that the White House would no longer risk supplying guerrillas fighting the Peoples' Liberation Army. Each of the 1,500 remaining rebels got 10,000 rupees to buy land in India or open a business. Many joined the refugees who'd fled with His Holiness.

There’s an irony to this story. The Tibetans who left achieved a kind of freedom. But they lost their Tibet, and in exchange the rest of the world got a small piece of it. But you can't sit and visit with these people and believe that, in the Buddhist spirit of things, they got the better part of the bargain.

They didn't. We did.

Plus: Check out Book Beast for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Stephan Talty is the author of Escape from the Land of Snows: The Young Dalai Lama’s Harrowing Flight to Freedom and the Making of a Spiritual Hero out this week from Crown. His last book was The Illustrious Dead.