“I’m in Eastern Ontario. Thousand Islands. Great Lakes. Doing what everyone else is doing in North America—trying to stay inside as much as possible,” Dan Aykroyd said on a phone call in April. Technically, he was outside at that moment. Aykroyd was walking around his family’s farm in Canada, which has the luxury of space and the drawbacks of weak cell service and several unfortunate incidents involving Aykroyd’s mouth and some wayward gnats.

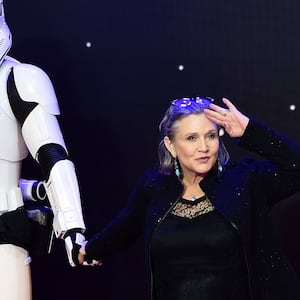

This summer marks the 40th anniversary of one of Aykroyd’s most famous and famously chaotic movies, The Blues Brothers. An outgrowth of the blues band Aykroyd and his co-star, John Belushi, played in on Saturday Night Live, the movie follows two brothers, Jake and Elwood, on a mission to raise $5,000 for the Catholic orphanage that raised them, encountering a series of blues and R&B all-timers en route—Aretha Franklin, John Lee Hooker, James Brown, Cab Calloway, and Ray Charles all make musical appearances—all while fleeing the cops, a resurgent Nazi movement, and an unknown woman (Carrie Fisher!) with a rocket launcher.

The movie’s production was barely less dramatic. Aykroyd’s first draft of the script, an unconventional free-verse sketch of a story that he wrote under the pen name “Scriptatron GL-9000,” went over 300 pages, before the director John Landis trimmed it into something palatable to studio executives. The budget, initially intended to max out at $15 million, wound up costing nearly twice that—$28 million—largely due to Landis’ obsession with cartoonish car stunts. For two decades, the movie held the record for the most cars destroyed in production (103!), until it was narrowly edged out by its sequel, Blues Brothers 2000 (104), and then 2009’s G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra (112). (Another possible budget drain: the cash they set aside for cocaine).

In advance of the anniversary, Aykroyd called from his farm to talk about the blues, the band, the movie, and the 40 years since.

I was hoping we could start at the beginning of the film, when you were thinking about adapting the band to a movie. Where did that start?

This is 40 years back now. We have 40 years of what I hope could be termed a project of cultural preservation. This is what we always came into it from the point of view of. I was a huge blues fan, growing up in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. I loved the Stax-Volt movement. I saw Otis [Redding] very early on. I saw Sam & Dave at the 1967 World Expo Fair, where they were playing in concert. I saw James Brown at the Esquire Show Bar and other venues. I was always just a college kid that just loved blues and R&B. I began to play and emulate the stars that I enjoyed seeing. I walked around like Paul Butterfield for a while, hair pushed back, shades, and a long raincoat. Charlie Musselwhite was a great one, of course. I began to listen to the great harp players, Carey Bell and Junior Wells and Slim Harpo, and just began to research blues music and the African-American songbook.

I also saw that, as I was growing up, it was kind of being swamped by popular music and not being recognized anymore. Disco was massive. Other artists were playing popular rock n’ roll. Some were giving props to the veterans. But there was a new generation that didn’t know about them. Just as there was a generation in my time that had to learn about blues through Paul Butterfield’s record East-West. We always thought that it would be fun to put an act together—sorry, I’m losing cell around here. Hello?

Yes, I can hear you.

We thought it would be fun, John [Belushi] and I, to put together an act that venerated the African-American songwriters and the songbook and the artists in a way that had humor, which was always there, if you recall. The classic band leaders—Wynonie Harris, Cab Calloway, Jimmie Lunceford, Johnny Otis—they were great musicians, but they were funny too. And they were great frontmen. They featured artists and stars that were much more talented, in terms of virtuosos on horns and piano and guitar. But the frontmen were very important.

We modeled the Blues Brothers on that. Let’s open our generation here, the SNL watchers, to the options, as it was opened to us. Let’s use what we know about Chicago, about blues and R&B. Let’s put together a Memphis-Chicago fusion band—which we did with Paul Shaffer and Tom Malone, who were our personnel recruiters. Otis was never going to play, but I can’t believe we actually got some of his guitar players. We got Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn, from Stax-Volt. We got Matt Murphy from James Cotton’s band. They were all from the South. But that was steeped in the Chicago tradition. So we had a Chicago-Memphis fusion band, with the—[coughing, hacking] I just swallowed a gnat!

Oh no!

Yikes! Anyway, that’s what happens in the summer up here. So, we had the horns from SNL, the guitars from the Stax-Volt, and an incredible 19-year-old drummer at the time, Steve Jordan, who’s gone on to become a big producer and one of the heavyweights in popular music today. With that, we just put together this superband. I think we did two shows there before we did the record. Our first gig was with Willie Nelson at the Lone Star Cafe.

Wild.

And Mickey Raphael. We said we want to come and try a few songs out and try this concept out that we’re working on. We put the uniform on: the briefcase, the handcuffs, the shades. We went in and did a couple of blues tunes—King B. and some others—and Mickey and Willie backed us up and got us started. Then Steve Martin said, Come and open for me, for my show at the Universal Amphitheatre. That really got us going. Because we were able to record the record with the money that Belushi got paid for Animal House. He put it into the record, and Briefcase Full of Blues went on to sell 4.5 million copies. I think Rihanna would be happy with that kind of sale today. That record is still popular today, and so I think what people got was that the music was great. When it came time to do the movie, we just had a magnificent canvas on which to paint our Chicago Catholic guilt story, and put in all of the stars that we loved in our youth. So, bringing back John Lee Hooker and Aretha Franklin and James Brown to get an increased focus on that generation. It was about preserving their legacy and letting their talent step out to give a whole new generation an enjoyment. Certainly, Aretha in the pink uniform is one of the great musical numbers ever.

I read somewhere that when you met John Belushi the first time, or maybe the second or third time, in Chicago, it was at a bar, and he hadn’t listened to much blues music.

It was in Toronto, actually. He came up to Second City. He came up to recruit for the Lampoon Radio Hour. He managed to grab Gilda [Radner] and take her back. She fell under his spell. I couldn’t go. I couldn’t go with him. He wanted me to come. We met on a snowy, blustery night at the Fire Hall Theatre, where we were doing Second City and of course, we bonded instantly. We went back to the club that I had, The 505, which was a speakeasy I had on a street in Toronto there, a late-night club. We were listening to the Downchild Blues Band. He said, I like this record, what is it? I said, It’s just a local blues band, you know the blues right? He said, Oh, I like heavy metal. He was into Grand Funk [Railroad] and Cream and all that. He knew that it all originated with the African-American writers and rhythms, in terms of the interpretations of Stax-Volt and the Philadelphia movement, all these great writers. He knew that that’s where the music he loved came from.

But then when I went back to New York, to explore SNL for my audition, he had this stack of blues records. He had gone home and he had to research blues records. By the time we were able to put together the album, he had half the songs picked—and a variation. They weren’t just all shuffles in C. It was an eclectic mix on all of our records. We did five. The songs are interesting, but they’re funny. We did the Perry Mason theme, if you can imagine. We wanted to respect the musicians and honor them, but also have fun and bring a new generation this music so we could share it with them. It all came from trying to put together comedy and music in a way that hadn’t been done before.

So then you released Briefcase Full of Blues, and a lot of the backstory for the brothers comes from those liner notes. When you were writing the liner notes, were you thinking that it could stretch into a longer story?

Well, Mitch Glazer, the screenwriter and director, wrote the liner notes. By the time we did the first record, Judy and John and I had kind of figured there is a story here. I had already been in Chicago the summer of ‘74, previous to SNL and previous to Blues Brothers. I was steeped in the city from being there with Second City over the summer of ‘74, when Nixon resigned. Of course, we were doing him onstage, selling cars at San Clemente Dodge-Chrysler. [In Nixon’s voice] We’ve got a great deal on a Dodge Diplomat, please come in, I will personally, personally take care of this sale.

So, I knew about Chicago. I knew about the corruption in the Cook County Assessor’s Office. I knew about the scandal that maybe the church properties were going to be taxed. That was a big deal. Oh my God, we can’t tax the Church! And I thought, there might be a little story here about the orphans. So I wrote a 300-page script. It was called Return of the Blues Brothers. It was two movies in one. It was the sequel as well. It was Nos. 1 and 2. I figured I’d better get it all down. Landis then distilled that into a shootable screenplay, and then we took that back together and then came up with the movie that you see in concert.

It’s exciting to think about maybe doing something on Broadway with it. It’s quite viable today. We have 40 years of cultural preservation, as recently as our concert in Windsor, Ontario, or at the Soaring Eagle Casino in Michigan. One of the tribal bands’ chiefs, one of the owners of the casino, walked up to me after my show, and he had a tear in his eye, and he said, “Man, boy, did I ever need that.” Because what you hear in our Blues Brothers shows, with Jim Belushi, the brother of John, we do them right.

Dan Aykroyd, James Brown, and James Belushi perform during the half-time show for Super Bowl XXXI between the New England Patriots and the Green Bay Packers at the Superdome in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1997.

Doug Pensinger/GettyOnce venues open up again, you mentioned something about Broadway. Do you plan to have another concert series or a live musical version of the movie?

I think it would be a story. Where do these brothers come from? What’s their origin? What made them the way they are? A pre-story. The challenge of doing the car stunts. The challenge of making some of the set. Bob’s Country Bunker is perfect for Broadway. Of course, we’d do it with younger stars. I’m not going to be up there hoofing it on Broadway. I’ll be sitting in the back doing notes.

You mentioned the original 300-page script included the sequel. Is that what turned into Blues Brothers 2000?

There are some elements in there. But not really, no. Blues Brothers 2000 was a flawed, somewhat acceptable companion to the first movie, maybe. But what I should have had in Blues Brothers 2000 is Queen Latifah as my girlfriend and dancing partner. She would have been the Blues Sister. But we were trying to get the thing made. And there was pressure from the studio, pressure to get the thing made, pressure to do things their way. I wanted to have Queen Latifah and Elwood on the road together, as both romantic and business partners. But that will have to be another time, in another universe.

Going back to the first Blues Brothers. You have some obviously very, very familiar faces in the film. There are just so many musicians in it. How did you go about contacting everyone and getting them involved? Were they all down immediately?

James Brown was. John Lee Hooker, yes. All of the members of the band, of course. Aretha, she saw the merits of it. She came into it with a little hesitation about wearing the uniform—the waitress uniform. That was her only hesitation, I recall. But then we made it so sexy and cute that, in the end, she loved it. Deborah Nadoolman, John Landis’ wife and costume director on the film, made the waitresses look so cute in the uniform. So, she was comfortable in the end. I mean, everybody pretty much came on. It didn’t take much convincing really.

I wanted to ask you about the cars in the movie. Were you actively shooting to beat the record of most cars destroyed, or was that just a coincidence?

No, no, I would say that’s accurate. We were, of course, on the lot at Universal and Hal Needham was directing Smokey and the Bandit and they were doing these things with cars that had never been done before. Everybody loved Bullitt. Car stunts started to come into movies. They were always there, of course, from the Keystone Cops on. But the way that they refined the stunts where you could put a cannon with a stump in it and flip a car, or where you could put a pipe rail to make the car look like it was driving over another and flip over, driving on two wheels—that’s the only thing I didn’t learn to do. I learned how to stunt drive pretty good in the movie. J-turns. 360s. We had a fast drag-race car for fast pickup scenes. We had four or five of the Bluesmobiles.

But Landis definitely wanted to race. He wanted to break a record, as to the most cars. We were watching Smokey and the Bandit. We were watching Hal Needham, Burt Reynolds, and other car stunt movies. So we got the best of the best, and the best drivers in the world to come with us, and cheat stuff that had never been done before. Jumping the bridge, putting the car through the tractor-trailer. There was a lot of breakthrough engineering that went into that stuff. The police cars were supplied by the city of Chicago. They were auctioning them off. We got a discount. We bought them all. I think there were 70 of them. Because we bought them all, we got a deal on them. I’m not sure what we paid for them. They were a few hundred bucks a piece. They were pretty beaten up. The city was glad to get the check, we were glad to get the cars, and we made those cars look like a hundred cars. We, maybe, wrecked four or five of them—maybe 15 in a day. Then we’d take them into the body shop at night and we’d turn back up in the streets with four, five, six repaired. And with the rest of the fleet from the day before, we could keep going.

One of the main stories to have come out of the movie was the budget, and all of the crazy things that included. As one of the creators, were you concerned with that at all? Was that a pressure on you or the business side’s concern?

In retrospect, that budget is pretty reasonable: $28 million. There were plenty of movies that cost as much at the time. It’s just that Universal had been sold a movie that they thought was going to cost $15 million, and then it cost 13 more. As a creator, I was absolutely policing it from the beginning. Landis had a scene in there where he wanted to go through a Rolls-Royce showroom, and destroy three or four brand new Rolls-Royces. And I said, John, no! So it was an Oldsmobile showroom and we didn’t wreck any cars—I don’t think, as I recall. Maybe one or two. Now, I wrote the thing big. I wrote it big, and then he sort of wrote some things bigger, and I had to go back and rein us both in, I suppose. But they got their money’s worth. Universal has made that money back, many times over. They’re way in the black on that now. They would tell you differently, and say it would all be in the hole. But that can’t be possibly true. With the TV sales and the merchandise, all the use of the movies over the years, videotapes and DVDs? No, they got their money back.

You’ve said that there was a part of the budget for cocaine. Was that a formal part of the budget? Was there a coke line item?

Well, no. There are always miscellaneous purses in a movie. Cash purses for various things—from paying off the local parking attendant or making people look the other way, or just, you know, we need another case of whiskey. That was a time when cocaine was a currency in America. It still is. It was commonplace. People were using it as a stimulant such as coffee, as the German population in World War II used, called Pervitin, which they got over the counter. It was methamphetamine. Every housewife was on it. Every factory worker was on it. Cocaine was a currency back then and we were working nights. So OK, wow, coffee—How do we get through? We gotta get through. A little motivation, a reward for some of the crew. At that time, people were using it. So, there was money set aside to get through the nights and a little reward at the end of the nights for our hard-working crew.

Dan Aykroyd attends the ceremony posthumously honoring actor/comedian John Belushi with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in Hollywood, California.

Vince Bucci/GettyI was not a user, but unfortunately, John succumbed to a cousin of it. Didn’t really do anything for me. But I’m not the judge. We’re all the captains of our own ship. It didn’t impact the performances in the movie. John’s performance in Blues Brothers is flawless. I saw it a little while back. He is so great in the picture. His gestures, everything, a hundred percent. And my performance as Elwood, buttoned right up to the top, you don’t see a glimpse of me as I live through my life. That was an absolute armored-shield of a character in there. I’m proud of that one. But coke had nothing to do with that. It was used for rewards and for night stimulation. And I would say that every other crew in the city did something similar. Steve McQueen was shooting another film there, Hunter. I bet they were buying from the same dealer.

How do you think, 40 years out, some of the social critiques—there’s a Nazi resurgence in the movie, and a pretty critical view of cops—those themes resonate now?

The Catholic Church is certainly a filter that you would be hard-pressed to write a movie about without addressing the abuse allegations, and the abuse cases, and the settlement of billions of dollars from the Vatican purse to try and mollify the damage that’s been done to young men and women all over the planet. In a way we were sort of hinting at that. With the nun and the pointer, we were hinting at, yeah, well, this was commonplace: corporal punishment, physical abuse, it’s just what you get it if you’re at a Catholic orphanage or school. It’s just accepted. We weren’t reaching into the depths of the evil of what came out of the actions of these wayward priests, but certainly we were acknowledging that this religion, this sect of religion, this Catholic religion did have darker elements. There’s that. I suppose the issue of recidivism comes up. The Blues Brothers will always be in trouble. When you’re raised in an orphanage, in an unstable home, you might be headed for this kind of life.