Blowing dandelion seeds into the wind isn't just a pretty little way for kids (and adults) to waste away a warm afternoon outside. They’re also an exceptionally effective way for certain species of plants to spread their seeds far and wide. Inspired by this evolutionary innovation, electronics engineers have just designed their own type of sensor that emulates the free-floating ability of dandelions to hang in the air and disperse through the wind.

The new sensors, debuted in a paper published Wednesday in Nature, open up the potential to create airborne instrumentation networks that could greatly boost applications in environmental monitoring.

“Our prototype suggests that you could use a drone to release thousands of these devices in a single drop,” senior author Shyam Gollakota, a University Washington engineer and coauthor of the new study, said in a press release. “They’ll all be carried by the wind a little differently, and basically you can create a 1,000-device network with this one drop. This is amazing and transformational for the field of deploying sensors, because right now it could take months to manually deploy this many sensors.”

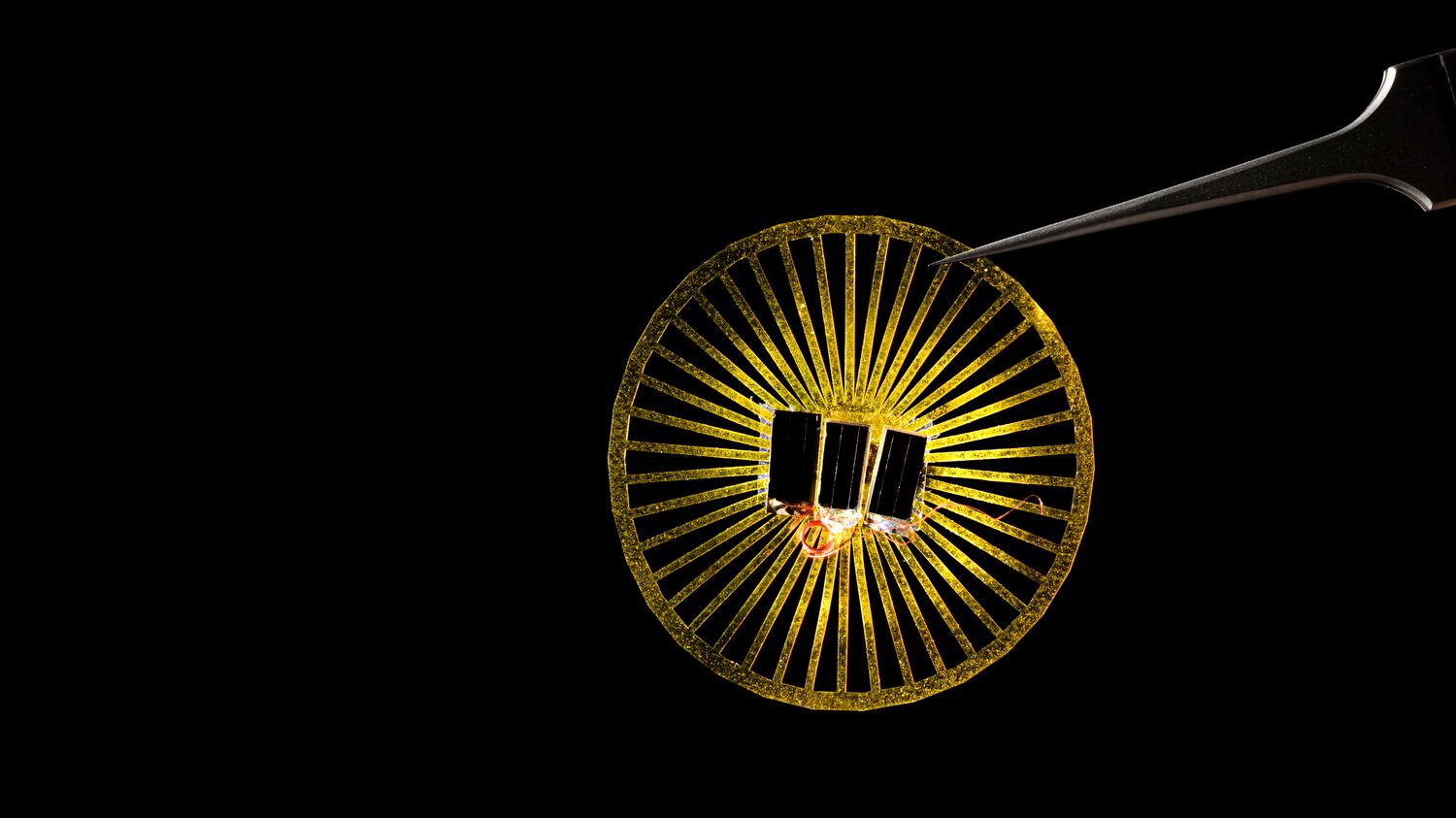

The researchers tested 75 different designs of the sensors, some of which are shown here.

Mark Stone/University of WashingtonThe new sensors, adorned in a brilliant gold color, have a mass of about 30 milligrams, so they are heavier than the average dandelion seed. But they still have to travel about 330 feet in a light breeze when released in the air. They operate without batteries, powered instead by tiny onboard solar panels, and are able to collect and send back data up to 200 feet away.

Gollakota and his team had to test out 75 different designs before they landed on one that was light enough to be tossed around by a breeze but still housed instruments that could provide some utility. The research team built versions of the sensors that could measure environmental data like temperature, humid, pressure, and light.

The main idea behind these sensors is that they could be a very inexpensive and easy-to-deploy approach to look at smaller, subtler changes in the climate or ecology that can’t be seen using satellites or static ground equipment. We could use this technology to help inform how farmers grow crops, or prepare a community against dangerous weather events.

The main drawback to these devices is that they effectively shut off when the sun goes down. They are also not biodegradable. Gollakota and his team want to improve the design to remedy both of these issues.

But even those obstacles notwithstanding, there are a myriad of directions to take these sensors—literally and figuratively. The future of climate research might simply be a dandelion poof of hundreds or even thousands of these sensors fluttering through the wind and arming scientists with data they once spent years trying to collect.