Daniel Prude was naked when Rochester, New York, police ordered him onto the snowy ground in March. The only thing besides handcuffs that officers placed on his body before he went unconscious? A white mesh bag commonly known as a “spit hood.”

Prude, 41, died of homicide asphyxiation on March 30, after a week in a coma. His demise began after he experienced an apparent mental health crisis, prompting his brother, Joe, to place an emergency services call. Rochester Police officers who responded found Prude naked and acting erratically. They ordered him onto the ground, where they promptly handcuffed him without incident.

Prude, who according to a medical examiner’s report had the hallucinogenic drug PCP in his system, continued to rant, and was later said to have alluded to possibly having COVID-19. He also spat on the ground. Police placed the spit hood over Prude’s head and knelt on his back until he threw up in the hood, after which he went unconscious.

ADVERTISEMENT

He never woke up again. “That was a lynching,” Joe Prude told The Appeal of the incident.

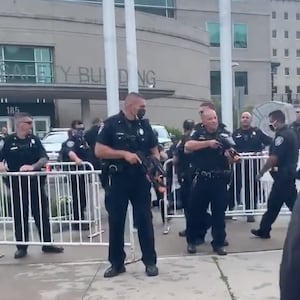

Prude’s death, which drew comparisons with that of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis Police in May, set off protests in Rochester after the racial justice group Free the People Roc released body camera footage of the incident on Wednesday. Rochester Mayor Lovely Warren suspended seven cops tied to the death on Thursday, while New York Attorney General Letitia James has said a state probe begun months ago remains incomplete.

“The Prude family and the greater Rochester community deserve answers, and we will continue to work around the clock to provide them,” James said Thursday.

Prude is the latest case to come to light of a Black person dying of asphyxiation or related causes in police custody. He is also the latest case of a Black man dying after police used a spit hood. The devices are theoretically intended to protect cops from spit and bites. But they can escalate encounters, veteran cops and law enforcement experts told The Daily Beast.

Maria Haberfeld, a professor of police science at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said the mesh hoods usually do not inhibit breathing—but they can.

“It allows you to breathe unless you have some specific condition, unless you vomit inside it,” or unless a person was sprayed with an irritant, Haberfeld told The Daily Beast.

Prude reportedly threw up inside the hood while three officers pinned him, handcuffed, to the snowy ground on his stomach. Body camera footage shows Prude asking officers to get off him, his speech becoming muffled and strained.

Officers are heard cracking jokes throughout the arrest as Prude goes limp beneath their knees.

Spit hoods, or any restraining device, are likely to escalate an arrest, Haberfeld argued. “People don’t respond well when someone tries to restrict their movements,” she said. “It’s a natural development.”

Brendan Cox, a former chief of Albany, New York’s police department, agreed.

“I remember using a spit hood from time to time when someone was being aggressive and spitting at folks,” Cox, who now works with the police reform group Law Enforcement Action Partnership, told The Daily Beast. “I certainly will not say they de-escalate the situation. You think about having something put over your head, people don’t appreciate that.”

Rochester Police have previously faced allegations of heavy-handed policing, much of it pertaining to aggressive crackdowns on small offenses, especially in minority neighborhoods. Several of those initiatives, over multiple decades, have led to allegations of racial profiling.

Cox said, when possible, he tried to talk the arrestee through the process, and remove the hood once the person agreed not to spit. But that’s difficult when the person is having a mental health crisis as Prude apparently was, Cox noted.

Cox questioned whether police should even respond to mental health calls, pointing to some programs across the country that allow social workers to answer 911 calls instead of cops or, at the very least, ride along with police and take the lead in mental health incidents.

Spit hoods have been implicated in the recent death of at least one other Black man undergoing apparent mental distress. 23-year-old Dujuan Armstrong died while in custody at California’s Santa Rita Jail in June 2018, after police restrained him and put a spit hood on him while he lay on the ground. Like Prude, Armstrong is seen on video going unresponsive, although a jail nurse does not appear to notice until after he stops breathing.

Two men—one intoxicated and one with a history of mental health issues—died while wearing spit hoods in 2015, after telling officers that they couldn’t breathe. Like Prude, one of the men vomited inside the hood, which Haberfeld flagged as a health concern.

Even when a person is not under distress or vomiting, spit hoods can be used as punitive measures for arrestees—not protection for cops—research suggests.

“Consideration must be afforded to the possibility that the use of spit guards represents a form of mechanical restraint rather than a means to prevent transmission of infection,” a 2019 study in the Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine found, noting the lack of data on officers who’d contracted infectious diseases from spitting or bites.

Prude’s talk about coronavirus shortly preceded—and appears to have at least partially prompted—police’s use of the spit hood. But the hoods might not even be effective against airborne viruses like COVID-19.

The Police Service of Northern Ireland began using the hoods on arrestees during that country’s COVID-19 lockdown, prompting questions from the human rights group Amnesty International. In a response to the group, the PSNI acknowledged that the hoods were not designed to protect against airborne pathogens like COVID-19, but said they might provide protection if a COVID-positive person tried biting an officer.

If anything, Haberfeld’s own research suggests a fall in spit hood use since COVID-19.

“I think officers would find it more difficult to justify now, given the fact that they’re wearing masks, unless there’s a specific threat that somebody is going to bite them.”

Body camera footage of Prude’s arrest suggests no such threat.