Biography is never merely destiny; plenty of people with complex backgrounds, interesting parents, and variegated ethnicities have never accomplished a thing. But sometimes heritage is an irrepressibly fascinating springboard for talent. Such is the case with Danilo Kis, the subject of Mark Thompson’s excellent new biography Birth Certificate: The Story of Danilo Kis, a volume that surveys the career of this unsung Yugoslavian novelist.

“Unsung Yugoslavian novelist” is not the sort of accolade that moves a book off of a shelf. But Susan Sontag, William T. Vollmann, Salman Rushdie, and Milan Kundera are all vocal fans of Kis. His work appeared in The New Yorker in the 1980s, and his novel A Tomb for Boris Davidovitch appeared in Penguin’s Writers From the Other Europe, curated by Philip Roth. Nadine Gordimer contributes a blurb for this biography. He is more than amply vouched for.

Kis’s work is gripping, a set of clever modernist experiments with a frequent core of deadly seriousness; imagine Kafka encountering the Holocaust, or Borges visiting the Gulag without losing a sense of humor and you have a rough approximation of Kis’s accomplishment. As Thompson writes, “Nobody did more to prove that Europe’s twentieth-century experiments in fiction can take the measure of its experiments in totalitarianism, without curbing the liberties of the one or blurring the crimes of the other.”

Even among the ranks of literary modernists, where rootlessness is a genuine but generally discretionary attitude, Kis’s cosmopolitan alienation stood out. The son of a Hungarian Jewish father and a Montenegrin mother, born in Northern Serbia, Kis’s life was already complicated at birth, and then became a good deal more so. His father had changed his name from “Kohn” to the more Magyar-sounding Kis in 1902, a move that may have involved prudential inspirations, but also might have proven voluntary. Hungary’s attitude towards its Jewish population was a good deal more progressive than surrounding states, and Jews were frequent acolytes of Magyar nationalism.

Kis was baptized into the Orthodox faith at 4; his family fled to Hungary in 1942, which remained, until late in World War II, an anomaly among the Axis powers, conventionally anti-Semitic but not genocidal. This changed in 1944, and German insistence prompted the large-scale rounding-up of Hungarian Jews. Kis’s father died in Auschwitz in 1944. The son was spared, and his survival is due to some combination of complex Hungarian determinations of “Jewishness” and possibly official inattention. The remainder of his youth was lived in Cetinje, the ancestral capital of Montenegro.

It is little surprise, given this complex background, that Kis found a home in literary adventurousness. He fused bold stylistic efforts with an exploration of the horrors of contemporary Europe. He made lifelong efforts to navigate currents of communism and nationalism in a Yugoslavian society that avoided the worst of the former ideology only to fall prey to the worst of the latter.

Kis pursued his education and early life amid the cultural ferment of Tito’s Belgrade, a place where sincere pursuits of socialist art and relative free expression coexisted in some equanimity. The Attic, Kis’s first published work from 1962, is a sort of free-form bildungsroman. The protagonist cavorts in an attic with Eurydice, and mulls over the meaning of life, death, and the genuineness of writing while grubbing for money and food. He leaves, sending Eurydice long fictional accounts of his travels. It’s not the most coherent of works, but it’s brimming with experimental energy and wit.

A darker turn followed, with several explorations of the Holocaust. Psalm 44 and Garden, Ashes are two works concerning the Holocaust as perceived by a child. But it’s the striking Hourglass that marks the culmination of this theme.

Hourglass reads as if the catechetical style of the Ithacan chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses were being applied not to life in 1904 Dublin but to Central Europe. The protagonist argues that Newton discovered gravity due to shit (“chronic constipation due to long hours poring over books”), imagines the effect of war on dogs, and unspools other thoughts of Joycean inspiration. But there are two aspects that raise Hourglass above mere Ulysses imitation. There is the alternating Kafka-esque narration that increases in darkness, and the gradual shift from a hazy and cryptic mitteleuropa to the specific circumstance of Hungary during the Second World War. What at first seems simply a deft homage comes to assume a dismal complexity.

This quest to infuse greater meaning into stylistic exploration was a lifelong one. Kis translated Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style, a collection of 99 retellings of the same story, into Serbo-Croatian. He read Borges and admired him, but the title of The Universal History of Iniquity gave him an immediate jolt. His quibble? “I claim that the universal history of infamy is the twentieth century with its camps—Soviet camps most of all.” Kis taught Serbo-Croatian at the University of Bordeaux in 1973 and 1974, and when his French students refused to believe the terrors of the Eastern bloc, he was inspired to write his most famous work, A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, a series of seven short stories that are basically micro-biographies nearly all ending in death.

Having largely declared naturalism insufficient to address the realities of 20th-century existence, he made the intriguing choice, as Joseph Brodsky has noted, to turn to biography, “the last bastion of realism.” While flagrantly aping a number of styles, Kis’s prose is, compared with much of his earlier work, straightforward; it’s the scenarios that are anything but. One story, “The Mechanical Lions,” describes the transformation of a Kiev brewery back into an ad hoc church again to convince a visiting French socialist that religion was not in fact being suppressed in the Soviet Union. In another tale, “The Magic Card Dealing,” about a Hungarian imprisoned in Siberia, there’s a lengthy musing on the tarot and other games of chance, their very randomness and irrationality a mirror for the impossible and deadly vagaries of existence within the Soviet State: “The entire literature of the lost continent is actually nothing more than an enlarged metaphor of this Great lottery in which winning is rare and losing the rule.”

A Tomb for Boris Davidovitch was published in 1976, and it soon attracted vituperative criticism from a number of leading intellectuals in Yugoslavia. Their accusation was that Kis was a plagiarist, which isn’t such a crime among modernists, as T.S. Eliot and James Joyce were accused of similar crimes some 50 years before. Although Kis did use material from nonfiction books, the affair displayed the Belgrade establishment’s resentment at Kis’s cosmopolitanism and his view that Europe’s cultural and literary history was his to use, with accusations that Kis was defaming “local traditions and contemporary currents in our literature.”

This scandal inspired Kis to write a series of broadsides against the nationalism that lurked beneath the surface of Yugoslavia’s enforcedly and putatively multi-ethnic society. These nationalist passions, he wrote, “follow logically from the kind of psychological, irrational, paranoid instability that sees phantoms everywhere, the kind of psychological and moral degeneracy that reduces everything to the common denominator of for us versus against us.” Kis won his criminal-defamation lawsuit, but these currents confirmed his principal residency in Paris, though he continued to spend time in Belgrade and Dubrovnik.

In Paris, Kis completed his last work, The Encyclopedia of the Dead, a wonderful collection of fablelike stories. The one from which the volume’s title was drawn is a Borgesian and suggestive tale about a secret society dedicated to the vision of an Encyclopedia of the Dead, to include the lives of people who do not appear in any existing books. Kis began to find increasing international regard, including in the West, but, not unsurprisingly, given his aversion to other labels, avoided any easy typecasting as “dissident.”

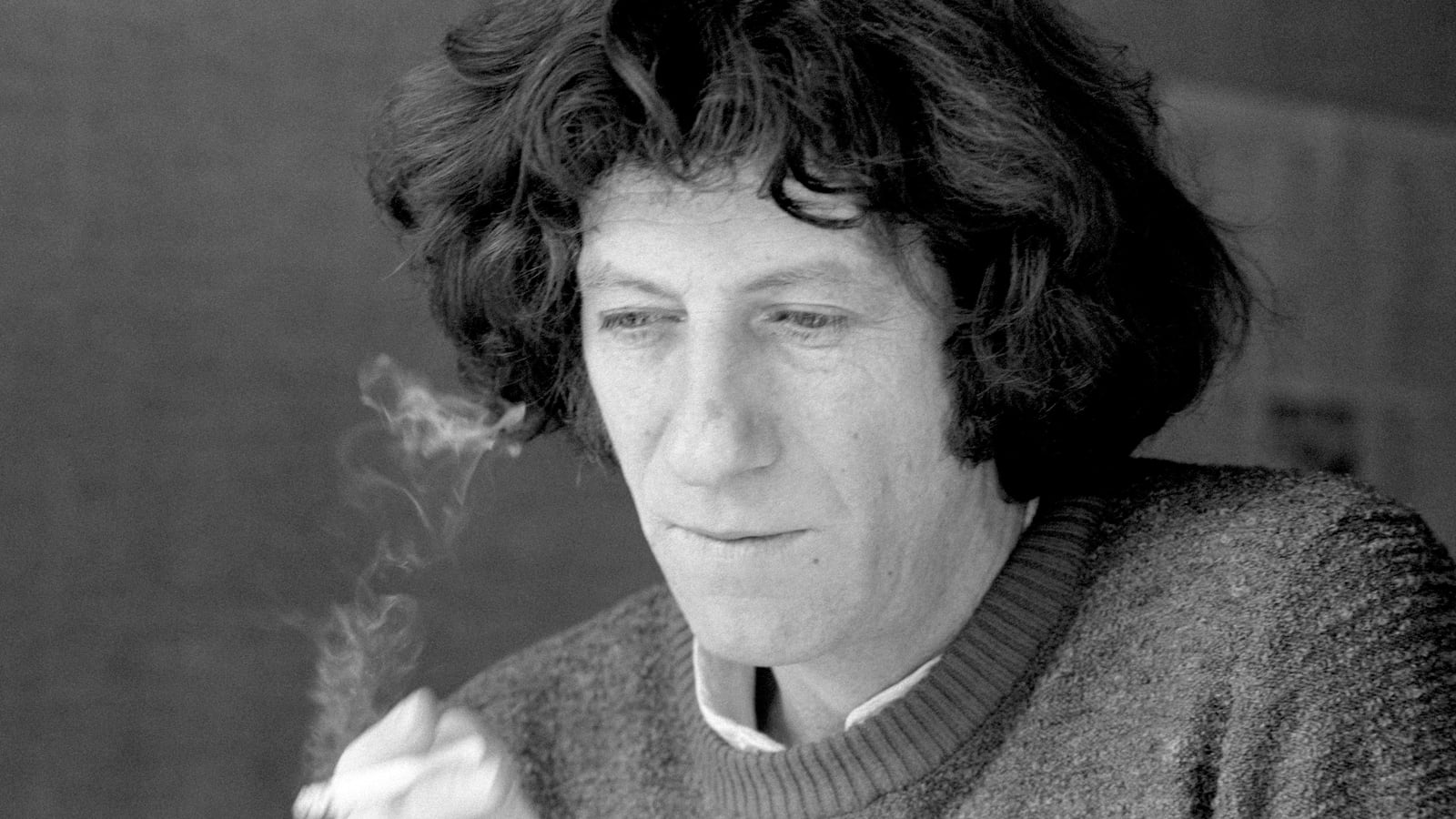

Like Italo Svevo, another wild hybrid modernist product of the region, Kis was fatally fond of cigarettes, and his increasing fame was cut short by lung cancer in 1989. This timing may have been a mercy, given the fate that was about to engulf Yugoslavia. Thompson notes that Kis used the term “Yugoslavia” only once in his work, but wrote dedicatedly in a Serbo-Croatian that was, however artificially, a stab at unity in a region riven by division. Kis’s life and work was not a revocation of place or of the local, but in countless ways a tempering of it, unto death. (He requested an Orthodox burial.) There were no simple answers to the problems that he and the region faced, but he attempted to respond with complex ones. As he wrote in an unpublished fragment:

For he—and this is truly what Central European writers do—drags around a terrible burden of linguistic and musical melodies; he hauls a piano and a dead horse behind him, along with everything that has been played on that piano and everything that that horse once bore into battle and to defeat—marble statues and bronze bearded busts, pictures in baroque frames, words and memories that nobody can understand outside that language, realia which in other languages need to be explained with long footnotes, wars, epic poems, epic heroes, historical and culturological data, Turkisms, Germanisms, Magyarisms, Arabisms each with its clear and precise semi-tone … For he (unlike a Russian, Frenchmen, Englishman, or German) cannot allow himself not to learn and know any language other than his own.