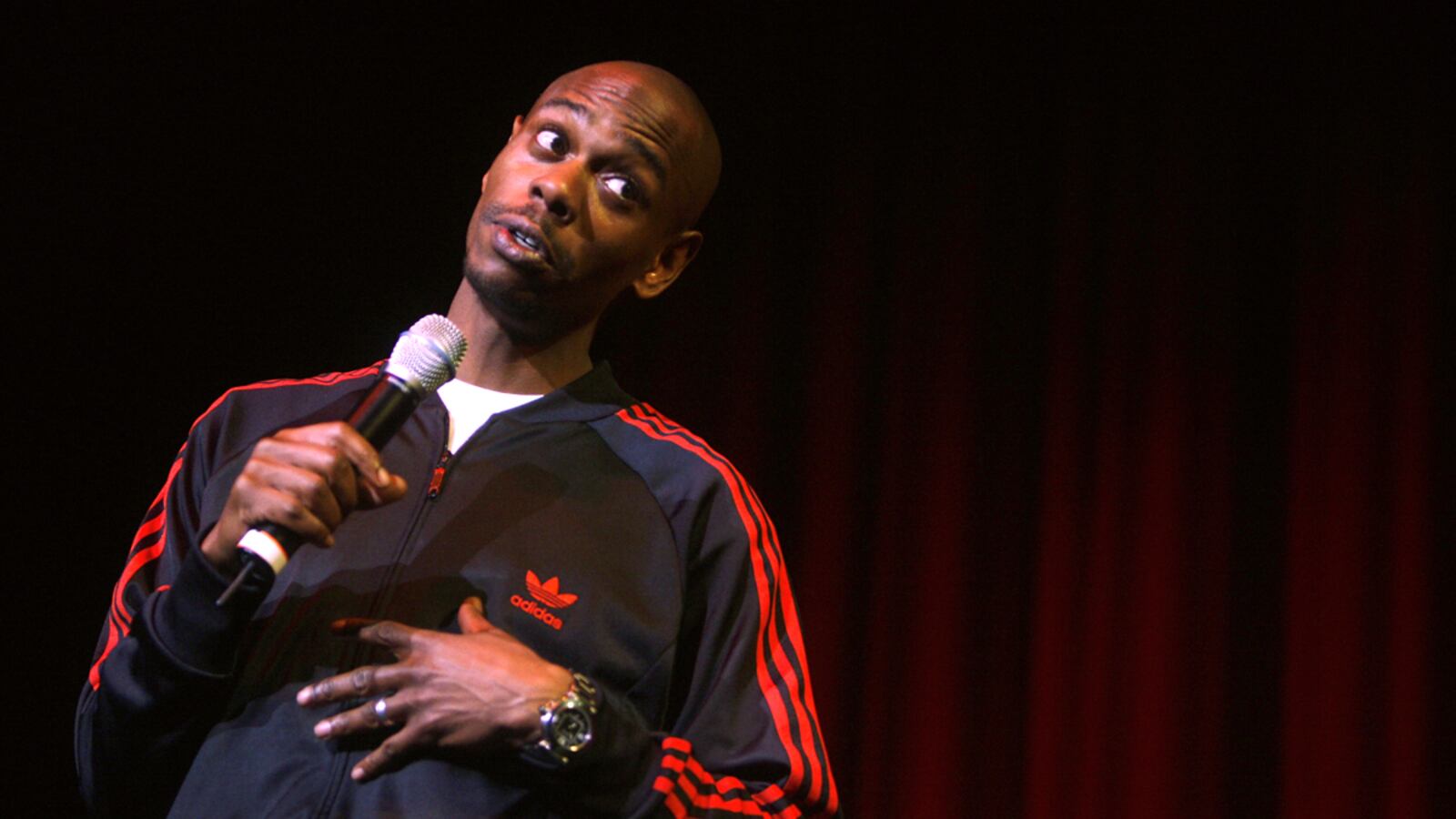

For years Chappellologists have talked about Dave’s secret shows, the pop-up appearances. “Did you hear about the one in San Francisco that lasted six hours?” “He did a set in Tokyo?” “I heard he did a 5 a.m. show in Chicago.” We dream of catching a Chappelle stand-up performance because he was one of the best stand-up comedians of his generation and because of the sense of mystery that’s engulfed him after he suddenly left Chappelle’s Show in the middle of the third season. Like Lauryn Hill and Bobby Fischer, he abandoned the stage at the top of his game with genius and potential to burn, leaving behind so many questions. Why did he leave? Would he ever come back? No one knew, but maybe, if you could see him do stand-up, you could somehow find an answer. Or at least catch a glimpse of the great artist at work once more. And then someone whispered in my ear: “Dave might be at the Comedy Cellar tonight. The 1 a.m. set. Maybe.” Whoa.

I’ve got two little kids who wake up every day about 6 a.m., so going to a 1 a.m. comedy show is a physical challenge. It’d be hard to remain awake that late, and I’d surely be a zombie the entire next day. Could I risk all that on a maybe? Yes. I had to try. I settled in at 1 a.m. and laughed at comic after comic.

But by 2:40 a.m. I wasn’t laughing anymore. My eyelids were so heavy that my eyes shut against my will, and my neck was soggy. Was he coming? Had I wasted a night and the next day for nothing? I would’ve been depressed if I hadn't been so sleepy. And then the MC said, “Welcome to the stage a very special guest …” I snapped to. And there he was. My heart leapt.

He opened with an aside—“I’m so washed up”—then launched into a long story about a man in a spandex bodysuit and boots walking across the street from him. “I’m not a betting man,” Chappelle said, “but if I was I would’ve wagered that he was gay.” The man sees Chappelle looking at him and crosses the street, making a beeline for him. “I know who you are!” the man says. “You’re Dave Chappelle!” As an aside Chappelle told us, “I was once a famous dude.” We had no idea where the story was going, and we were on the edge of our seats. The man said, “I need your help, Dave!” He said he was gay and from the future and only Chappelle could help him. “You have to stop my father! He’s evil!”

“Who’s your father?”

Calmly, he delivered the punchline: “Tracy Morgan.”

The room exploded.

Then Chappelle laid back, bummed a cigarette and a light from audience members, and proceeded to meander through an hour-long set. Fellow Chappellologists, I am here to report that his comedy muscles remain cock diesel. His set was unpolished, he admitted as much. There was no theme and appeared to be no pre-planned order. He lurched from story to story and sometimes into improvisation with no reason for or momentum to his overall line of thought. But most of the stories he strung together were brilliant bits. He was letting us watch him practice, and Chappelle going through the motions is better than the vast majority of comics doing finished work. He moved through stories about recent news events—Anthony Weiner, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Tracy Morgan—and then paused to ask the audience what he should talk about, almost letting them direct the show. Someone shouted out, “Who’s worse? Arnold or Tiger?” Chappelle absolved them both and then moved into a bit about Tiger. When someone brought up Casey Anthony he claimed to have not heard about her. The outline of her story was given. He said sarcastically, “Now, that sounds funny.” Then he said, “I’m gonna read up on that. Next time you see me I’ll have 45 minutes on her.”

His bit about Tiger was based around the idea that he could’ve done way more. He’s a billionaire. Anything you or I could imagine, he can make happen. “You know what’d be great?” Chappelle said from Tiger’s point of view. “If I could get an alligator to bite my balls. But with just the right amount of pressure.” Three calls later he’s got someone on the line promising he can deliver just such a thing. “How much?”

Chappelle-as-Tiger said, “OK. How long would it take you to train it? Three months? OK, I can wait.”

About Weiner he said, “What good is the Internet if you can’t send pictures of your dick to people?” He later said he was going to start a website called Picsofyourdick.com with pictures of, well, you know. “To level the playing field,” he said. “Because of the Net you can’t be judgmental of anyone because everyone’s stuff is right there. I miss that.” There’s Dave’s brilliance—the outside of the idea was juvenile, but at its core it was a smart concept, the impact of the Internet on shame in modern society and how the Net’s inability to forget anyone’s foibles makes it harder to laugh at other people. I’ve read fuller unpackings of that idea in articles in The New York Times Magazine and Wired.

In the spirit of practice, Chappelle sometimes gave us endings without bits attached. He said, apropos of nothing, “The punchline was: And I realized I was smelling my balls.”

In many of the bits his fame was referenced in passing or directly. One story had him receiving a package at home with a note that had one word on it: “Gotcha.” Inside was a VHS tape. He races around the house looking for a VHS player—who has one of those anymore? He finds one in a closet and pops in the tape. It shows Chappelle having sex with a woman not his wife before he was married. Chappelle looks at the clock. His wife would be home in 15 minutes. “So,” he said, “I quickly jerked off to the tape.” Natch. Then a week later another package arrives. Another VHS tape. It’s a tape of Chappelle jerking off to the first tape! “So I jerked off to that.” The bit killed—nearly all of his punchlines did—but there you could see his fame creeping into his psyche and you could see his paranoia about being watched. This, even while he’s able to have fun with the fruits of being stalked.

In one key bit he discussed talking to groups of kids. He was asked to give them a piece of advice from his life. He said, “Don’t quit your show. I don’t know how any of y’all get by without a show.” Is he truly regretful, or is that just the funniest thing to say about all that? I interviewed him shortly after his return from self-exile in South Africa, and he seemed very settled with his decision to exit Chappelle’s Show. No one had forced him out.

But for me the important point wasn’t whether he was being honest or just being funny in saying, “Don’t quit your show.” The most telling part of that moment is that now Chappelle cannot do comedy without discussing himself, without doing surgery on his image. He must mention the show and the mysterious exit and that he “used to be a famous guy,” and the characters in his stories must recognize that he’s Dave Chappelle and act on knowing that fact or it’ll seem false that they don’t know him. Or he won’t be taking full advantage of the comedic potential if they don’t recognize who he is and react to that. Chappelle has become part of his own act in a way that recalls no comic since Pryor after he set himself on fire.

Most comics come out and do sketches and bits and aren’t a part of their own act. Steve Harvey and Ricky Gervais can do an hour without talking about themselves. Bill Cosby talks about his life, but it's normalizing, it's about him being a regular guy. Chris Rock opened Kill the Messenger with a bit in which he takes his family to Africa for a photo safari and eventually realizes everyone’s pointing their camera at him. When Rock talks about Rock onstage, it’s almost always innocuous; he's saying, "People notice me." The same night I saw Chappelle, uptown at Caroline’s Tracy Morgan was performing. Nowadays he must take a break from his set to do a bit about himself because of his homophobic comments. But that will pass, and a year or two from now Morgan will be back to doing stand-up without doing bits about Tracy Morgan.

Chappelle will forever have to talk about Chappelle—and by that I mean “Chappelle,” as in the icon who’s larger than him, the person who exists in others’ minds, not someone he sees in the mirror but someone he sees when he looks at the sum of his onstage/onscreen persona in his mind. Becoming such a big part of your own act suggests, perhaps, unwanted self-scrutiny. Because deconstructing yourself can be psychologically painful. You want to avoid doing that too much because it can mess with your head. You want to know why you’re famous, why you’re connecting with the audience, and what they want from you, but too much reflecting on “you”—i.e., the person the audience and the media see outside of the real you—can cause you to flip out. It’s just too damn meta.

At 3:45 a.m., shortly after repeating, out of nowhere, “Don’t quit your show,” Chappelle let the show end. There was no big, hilarious finishing bit. It kind of petered out and he was gone, back to the shadows. At a recent show in San Francisco he talked about a comeback without defining what that would even mean. That night at the Cellar, the word "comeback" was never even uttered.