Britain’s Parliament rose for its summer recess today. Ministers and backbenchers will pack their bags for Tuscany, Provence, or, for those keen to be seen vacationing at home, Cornwall. The recess could scarcely come soon enough for Prime Minister David Cameron, for whom summer offers a welcome break from the ghastliness of the News of the World phone-hacking scandal and his own decision to employ a former editor of the now-shuttered tabloid to run his press and communications shop.

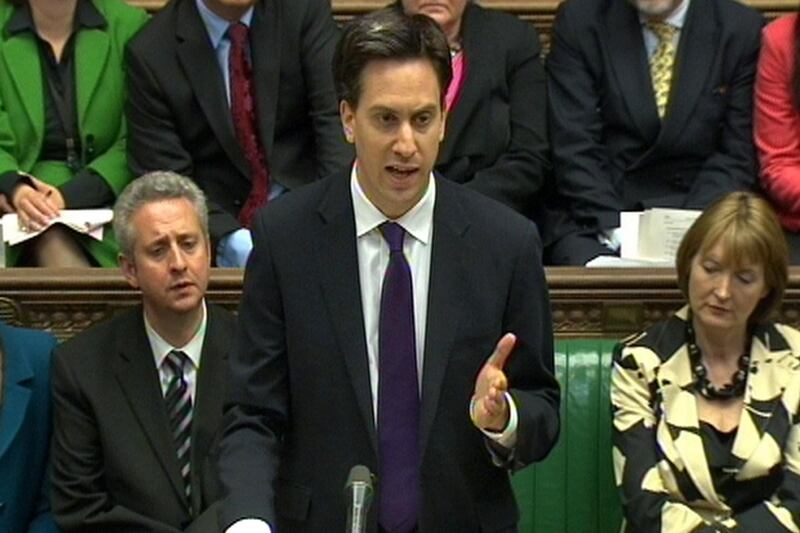

If summer is the sweetest season for Cameron, the break has come at a bad time for Cameron’s principal opponent, Ed Miliband. The Labour leader has had a good crisis and for almost the first time appears to have found his voice. It was Miliband who appreciated—much more quickly than Cameron—that this crisis offered the chance for the leader of the opposition to make his mark.

Standing up to Rupert Murdoch has boosted Miliband’s credibility on the left and, for perhaps the first time, helped him to “cut through” to the general public. When Miliband tabled a motion demanding News Corp. abandon its bid to purchase the 61 percent of BSkyB it does not presently own, it was seen as an odd, even quixotic, move. Few British politicians have dared challenge Murdoch like this.

It swiftly became apparent, however, that Miliband had a better grip on the public mood than his critics appreciated. With few Tory MPs volunteering to defend the Murdoch interest, the government indicated it was not going to oppose Miliband’s motion. Faced with unanimous parliamentary opposition, News Corp. took the hint and announced it was abandoning its takeover bid. (Though it reserved the right to return to the matter at some undefined point in the future.)

What’s more, Miliband is trying to slot the phone-hacking scandal into a wider narrative of over-mighty institutions losing touch with the people they are supposed to serve. Taming these institutions and curbing their excesses should be a task for a renewed Labour Party.

Miliband’s diagnosis is that the banking crisis, Westminster’s own expenses scandal, and now this latest disgrace are each symptoms of a common problem.

In astringent, austere times, Miliband is inching toward a refreshed populism with which to combat the slick, suave, wealthy duo of Cameron and his coalition partner Nick Clegg.

If this seems mildly familiar to American readers, then it should for it is, in large respect, a reprise of “The People vs. the Powerful,” much-favored by quasi-legendary, serial-loser Democratic strategist Bob Shrum. The former Kennedy, Gore, and Kerry adviser was closer to Gordon Brown than he is to Miliband but it is Brown’s successor who seems determined to follow a Shrumian agenda even if he’s not actually officially calling on Shrum for advice. At some point, this approach might work, even if it has not been notably successful in national elections in either Britain or the U.S. in recent times.

Unfortunately, it is possible to have a “good” crisis without this being reflected in the polls. Cameron’s net approval rating has only declined two points (from -10 to -12) and Labour has not, or at least not yet, enjoyed any Murdoch-related bounce in the polls. The only significant movement in the polls is that Miliband’s appproval rating has improved from -34 to -21.

In other words, Miliband’s position has improved from “disastrous” to “very bad.” This is, in one respect, a major advance even if most observers believe Labour’s lead in the polls is “soft” and largely the product of economic uncertainty. The next election is not due for another four years and the Tories are not running scared yet. The combination of a sluggish economy and public spending cuts was always likely to cost the government a great deal of goodwill.

It is not Miliband’s fault that he neither looks nor sounds like a potential prime minister. But until he discovers or acquires some measure of gravitas, he is unlikely to persuade the public that, whatever Cameron’s weaknesses, he’s a fit and proper person to occupy 10 Downing Street.

Fortunately Miliband is having an operation to remove his adenoids this summer, a procedure that may result in him sounding a little less like a teenage dork. This may seem a harsh assessment but not even the Labour leader’s admirers claim that “presence” is one of his best attributes.

Miliband says the operation is not connected to any desire to make his voice more appealing to voters. Instead it is designed to alleviate the sleep apnea from which he suffers. His wife will be thankful for that, but so may Labour supporters if the operation improves Miliband’s voice. (He would not be the first leading politician to change his voice: Margaret Thatcher received coaching to change her own voice and pitch, making it less harsh or grating.)

Miliband’s criticism of Cameron has been based on a simple idea: “He simply doesn’t get it.” Hiring Coulson was the original sin that prevented the prime minister from acting more decisively before it became impossible for him to avoid doing so. The fallout from that decision has yet to be fully measured and it may yet be the case that Cameron will face further embarrassment once the multiple inquiries into the scandal begin to report in the fall.

For the time being, however, the evidence suggests the public views the scandal as simply confirming their already low opinion of politicians and journalists alike. This being so, it has not radically changed their views in any serious or significant fashion.

If this remains the case then Miliband’s bad luck will be to excel, relatively speaking, on an issue of great concern to the Westminster and Fleet Street villages but that does not seem to have captured the public’s imagination or changed voters’ views of the principal political parties. If that remains the case, Miliband needs a better story to tell on the economy, welfare, and crime if he’s to translate the progress he has made this past fortnight into major, longer-lasting gains.