“Be thankful you weren’t alive in the 60s.”

That’s the best I can do in the way of consoling words for young people who in the last two weeks have listened to their parents and grandparents reliving John F. Kennedy’s assassination for the umpteenth time.

If the torrent of 50th anniversary articles, symposia,blog posts, TV documentaries and docudramas, historical reenactments, new books, and reissues has left you aghast at the bottomless self-involvement of your elders, please keep in mind that the deluge this month is nothing compared to the steady rain that fell on us almost every month between 1963 and 1967.

Remembering JFK became an industry in those years. The double murder of a U.S. president and his suspected assassin—within 48 hours of each other--multiplied expon-entially the number of angles that journalists, historians, self-appointed gumshoes, and total crackpots could pursue. The light that bounced off those shattering events, somehow mirroring each other, has many of us still trying to see straight and fit the pieces together in a logical pattern.

Would Kennedy be so revered today had he not been shot and killed in Dallas? The question isn’t improper. The 100th anniversary of his birth in 2017 is unlikely to provoke this scale of outpourings. Of the estimated 40,000 volumes devoted to his life and presidency, more than 2,600 are concerned solely with the circumstances of his last day on earth.

Fueled by myth, the enduring fascination with JFK has depended, as many myths have, on our less-than-noble taste for sexual intrigue and gruesome death. Don’t let it be forgot that Camelot, despite what Jackie wanted us to think, was a story about infidelity by beautiful people who brought down a government. It does not end happily.

***

Four major players—organizations and individuals--tended the flame of JFK’s memory in the years following his death. Their motives were the usual mix of the honorable, the base, and the subconscious. But whether acting out of grief or curiosity--the mystery of Kennedy’s death was the journalistic story of the mid-60s and turned dozens of ordinary citizens into investigative reporters--it wasn’t hard for all sorts of people to make money off the public’s fascination with an assassinated president.

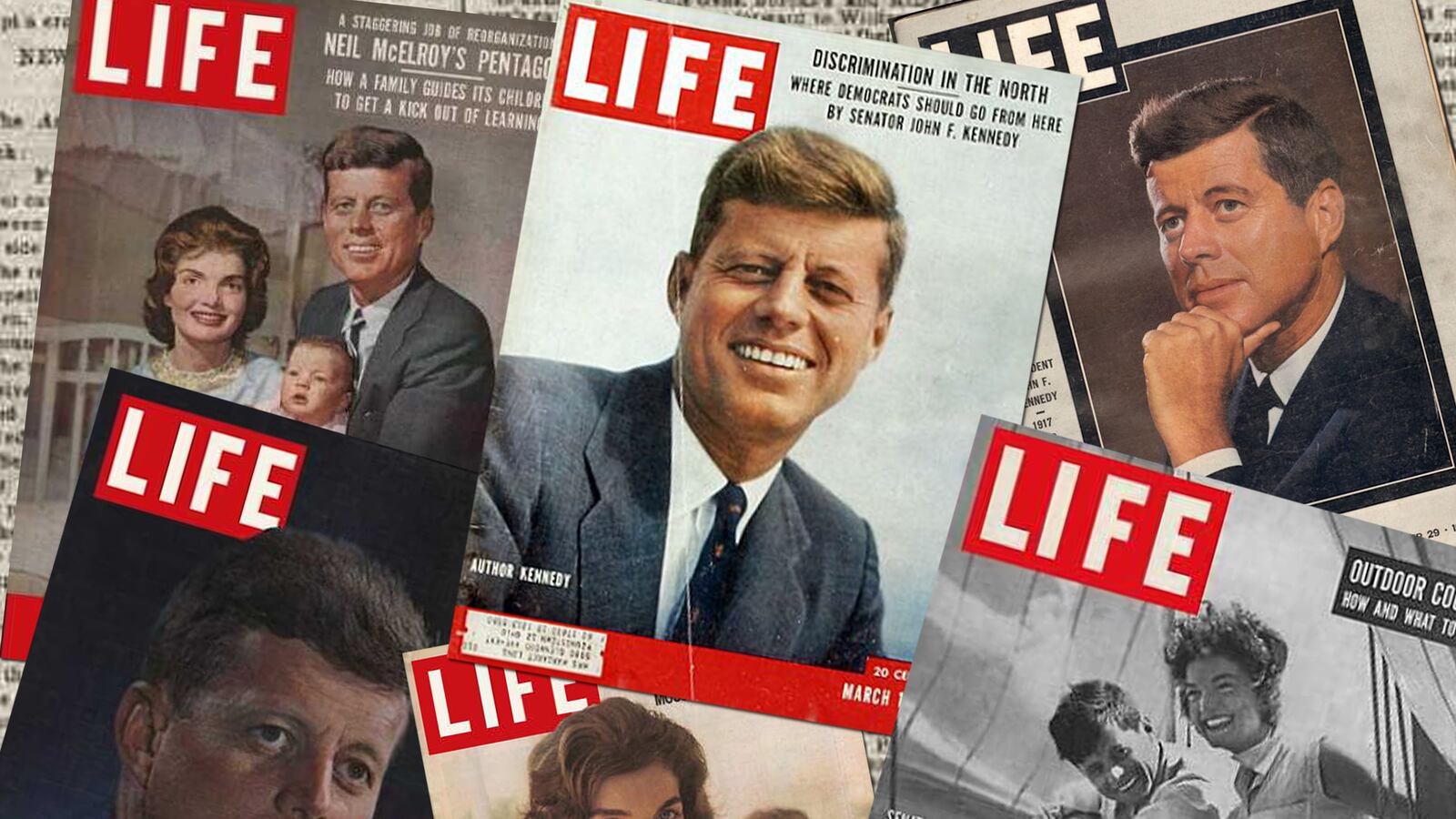

First on my list of those with a stake in JFK, Inc. would be the picture magazines, Life and Look.

In our media-liberated age, it is hard to grasp the almost monopolistic hold the large-format weeklies enjoyed over any news that could be photographed. Circulation numbers don’t reflect their impact or ubiquity. (Life peaked in 1969 at 8.5 million subscribers; Look was not far behind, with 7.75 million that year. This was a time when the U.S. population was just reaching 200 million.)

Before TV took over the role--and JFK’s assassination marks a key phase of the transition—Life and Look andThe Saturday Evening Post were charged with illustrating and interpreting national and world events for the white middle class. Between 1963 and 1967, Life devoted 10 covers to JFK. (During these years only the cover of Time was a more valuable piece of journalistic real estate.) Three covers alone appeared before the end of 1963: "Murder of the President” (Nov. 29); "Kennedy's Last Journey” (Dec. 6); and an undated "John F. Kennedy Memorial Edition." These issues were extremely popular, cherished even. Copies can still be found in attics all over America.

In the months that followed, the editors turned their focus to JFK’s accused killer. "Lee Harvey Oswald" (Feb. 21) and "Oswald's Full Russian Diary: He and Marina in Minsk" (July 10) were both covers, and when the Warren Commission released its report, Life asked committee member (and future U.S. president) Gerald Ford for his first-hand assessment of the findings (Oct. 2).

A magazine war broke out in 1965 over which one would publish the first official history of JFK’s life. Life excerpted Arthur Schlesinger’s A Thousand Days over two issues in summer and fall. Look retaliated by devoting three issues to Theodore Sorenson’s Kennedy. Finally, in 1967 Look trumped its rival by publishing William Manchester’s The Death of a President: November 20-25, 1963 in four separate issues.

All of these books became best sellers. Every year from 1963-67, at least two of the top ten best-selling books of the year were either by or about JFK. (In retrospect, the mid-60s not only was the high water mark for still photography in magazines but for text as well. Manchester’s tome runs more than 750 pages.)

Life also controlled the key piece of visual evidence from the assassination: Abraham Zapruder’s 26.6-second home movie. Richard Stolley, a Time-Life editor, had locked up reproduction rights only hours after becoming aware of the film’s existence. The magazine paid an estimated $150,000 and zealously protected its copyright.

Reproductions of the 486 still images from the 8 mm strip of celluloid were scattered for years through various issues, although the editors were sensitive not to reproduce frame 314, the fatal head shot. Meanwhile, frame 230, which shows the presidential limousine against the hill at Dealey Plaza, became the basis for another cover story, "Did Oswald Act Alone? A Matter of Reasonable Doubt” (Nov. 25, 1966).

Increasingly challenged by the need to come up with fresh approaches when JFK death anniversaries rolled around, they hired former Texas Gov. John Connally in 1967 and had him reconstruct the Nov. 22 trip with his wife and the First Couple for a cover story, "Why Kennedy Went to Texas." Again, the piece was illustrated with stills from the Zapruder film.

Until 1968, when the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were only two cataclysms that dominated the news, JFK proved to be as reliable a money-maker for Life as reports about the space program. By 1988—the magazine ceased to exist as a weekly in 1972 but was revived as a monthly from 1978-2000--one or another Kennedy family member had appeared on the cover of the magazine 48 times.

The second group that would not leave JFK’s body alone after his death, and benefited from the conspiracies swirling around his and Oswald’s killing, were the news divisions of the TV networks, especially those of CBS and NBC.

Among the striking aspects of broadcasts from that November weekend is how little TV had to work with. News of the shots fired in Dealey Plaza was first reported on radio. TV had to scramble to put anything on the air and often it was nothing but an anchorman in a New York studio.

Walter Cronkite’s announcement of the president’s death is iconic because of the suppressed emotion evident in his voice and the removal of his glasses. It marks Cronkite’s aggrandizement into fatherly comforter-in-chief.

But the paucity of other visual reports from that day has also magnified the moment’s significance. Oswald was shot two days later, it could be argued, because of the media’s need to fill a yawning news void. Since Friday there had been almost nothing to show a curious public about either the assassination (indeed, the Zapruder film was not broadcast until 1975) or the suspected killer.

The networks pressured the Dallas police to let them film a jail transfer that should have happened in secret, out of camera range. The police eagerly agreed to this absurd proposal so that Oswald’s good health would be apparent. (His black eye had ignited rumors he was being brutalized in custody.) As a result, NBC and Tom Pettit broadcast Ruby’s shooting of Oswald live, in real time—the first time Americans had seen someone executed in front of their eyes. CBS lagged a few seconds behind because Roger Mudd had gone on too long in a stand-up from Washington, D.C. But they made up for the blown opportunity with videotaped repeats. That weekend initiated the phenomenon of saturation TV coverage.

Things only got worse. Some 23 TV network specials about the assassination--retrospective and/or investigatory—appeared between 1963-1968. Even when the topics seemed focused on legitimate areas of inquiry, such as Cuba’s, the Mafia’s, or the CIA’s possible connection to Oswald, it was hard to miss their self-congratulatory air.

As Barbie Zelizer pointed out in her 1992 book, Covering the Body: The Kennedy Assassination, the Media, and the Shaping of Modern Memory, most of these performances of “journalistic recollection were identified by an individual reporter’s name.” Dan Rather hosted more than one of these. “By coming back to film clips of Rather, the documentary supported his central presence as its narrator and under-scored his part in the network’s original coverage of Dallas.”

Rather is among dozens of newsmen summoned back every late November to recall again for the cameras where they were during those fateful four days. By dying as he did, JFK probably launched more journalistic careers than he had when alive.

(One historical aside: On Dec. 10, 1963, after pretty much all-JFK-all-the-time for two weeks, Cronkite’s CBS evening news broadcast had a light-hearted feature, one originally scheduled for Nov. 22. It was about the sobbing teenage girls enthralled by an English group called The Beatles—their first appearance on American television.)

The third group that enhanced JFK’s posthumous aura, however inadvertently, was the Warren Commission. Authorized by President Johnson a week after the Dallas killings to gather evidence, record memories of eyewitnesses, and perhaps to quiet fears of a conspiracy, the 7-member panel, headed by the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Earl Warren, released its 889-page report less than 10 months later.

It was widely hailed at the time as definitive. Questions about more than one shooter were dismissed. The findings were “unanimous on … all questions,” The New York Times inaccurately reported. (Three of the seven members doubted the so-called single-bullet theory.)

Then, in 1966, Mark Lane published his seminal book Rush to Judgment, with the pointed subtitle: A Critique of the Warren Commission's Inquiry into the Murders of President John F. Kennedy, Officer J.D. Tippit and Lee Harvey Oswald. Lane did not believe that the same bullet that went through Kennedy could have wounded Connolly. His book, along with Josiah Thompson’s Six Seconds in Dallas and Edward Jay Epstein’s Inquest: The Warren Commission & the Establishment of Truth, became 1966 bestsellers.

The failure of the FBI to interview many eyewitnesses, some of whom disputed the report’s findings, quickly became a source of controversy. Some of these people aired their misgivings in a 1967 documentary film directed by Emile de Antonio and based on Lane’s book. Filmmaker and author became heroes on the counter-culture circuit in the late ‘60s as they toured their work on campuses around the nation.

The Warren Report faulted the Secret Service, which took the criticism to heart and revamped its practices. But the news media was also blamed for what happened in Dallas, especially for its role in Oswald’s death, and that may have helped to turn the media against the findings.

Within three years of Kennedy’s death, some 200 books about him were published. Most of the early ones were first-person reminiscences or historical encomiums. But after 1966--and increasingly thereafter, until the end of the century--the tone darkened. Lane’s view that a cover-up had obscured the truth about JFK’s death soon became conventional wisdom. (British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who went on to make a fool of himself by vouching for the fake Hitler Diaries, wrote the introduction and gave Lane further credibility.)

Only in the last decade has the labor and judgment of the Warren Commission and the FBI been appreciated again. They interviewed hundreds of witnesses, analyzed hastily written by forensic documents, and put together a coherent report in only 10 months--record time for a Washington panel. The wheel has turned, and the Report’s endorsed view of Oswald’s acting alone has once more become the standard interpretation.

There’s no denying, though, that it left a dividing line. Depending on where you stand on the issue of a possible conspiracy, the other side is bound to label you either a “government stooge” or a “grassy knoll nut.”

The fourth, and most important player in making sure we would keep talking about Jack Kennedy was Jacqueline Kennedy. Worries that he had suffered an ignoble death, at the hands of a nobody, and in an alien city that had openly hated him since 1960, terrified her.

“He didn’t even have the satisfaction of being killed for Civil Rights,” she reportedly told her mother. “It had to be some silly little Communist. It robs his death of any meaning.”

To prevent that from happening, she behaved with steely dignity, first in the hours after he had died bloodily in her arms, and then during the weekend as she stage-managed the spectacle of his funeral back in Washington, D.C.

Understated symbolism was her style: the caisson drawn through the streets by a riderless horse, accompanied only by the low rumble of drums; and a closed casket for the victim of a head wound was her demand. Her whispered suggestion that her 3-year-old son salute the passing casket of his father resulted in the most wrenching photo (by UPI’s Stan Stearns, later reproduced in Life) of a wrenching weekend.

She requested an eternal flame be placed at JFK’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery—he would be the only president to be so memorialized--and she played a pivotal role in the site’s orientation on an axis with the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial and the U.S. Capitol.

Guardian of access to all kinds of information about the Kennedy presidency, she enjoyed journalists if they played by her rules. Camelot was her invention. Theodore White was happy to promote the myth in Life, bathing the years when the couple occupied the White House in a celestial light.

She also stayed in close touch with Schlesinger as he was writing A Thousand Days, and with Manchester, until they had a falling out, reportedly over his attempts to write more candidly than was the norm about her husband’s reckless private life.

No other 20th century U.S. president, except FDR, had a widow as prominent as Jackie. Her fame in the 60s and 70s rivaled that of any celebrity in the world. Photos of her anywhere were the ultimate paparazzi prize. Until eclipsed by Princess Diana, she moved magazine copies like few other women of her time.

And, to her credit, she did not take advantage of her role as the former First Lady; if anything, she ran away from that public image. Her own posthumous standing has hardly diminished either. She has been portrayed no fewer than 20 times in TV movies in the last 10 years.

There are no signs yet, to paraphrase W.H. Auden, that the dreadful martyrdom of JFK has run its course. Our obsession is as morbid as ever. Perhaps the chief blessing of the media eulogies we’ve just been witnessing is that many of us who remember where we were that November weekend won’t be able to remember anything soon. Fifty years from now almost everyone who was alive then will be dead.