When Democrats flipped a GOP-held state legislative seat in New Hampshire last week, not only did it barely make news nationally; it barely made the news in New Hampshire.

A sleepy special election to win one of the Granite State’s 400 state House seats—more than a year removed from the 2022 midterm elections—does not carry obvious political import.

But in the eyes of some Democrats, this election in a tiny slice of a small state might have huge consequences because of how they won it: on a closing message that relentlessly hammered the GOP candidate over abortion.

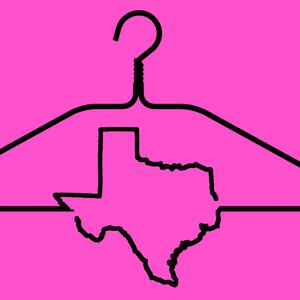

In the final week of the election, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed a harsh new abortion law in Texas to stand, effectively banning the practice in that state and putting abortion access nationwide in its most tenuous position in decades.

The Republican candidate in the New Hampshire race, Linda Camarota, voted in favor of anti-abortion bills when she served in the legislature. So naturally, after the high court’s decision on Sept. 1, Democrats rushed to connect Camarota with the Texas law.

They sent a mailer to voters in the district and argued that Camarota’s record “shows she’d stand with legislators who just banned late-term abortion without exceptions for fatal fetal anomalies, rape, or incest.” And in other mailers, the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee—the party’s official national arm for state legislature races—talked up the Democratic candidate, Catherine Rombeau, by claiming she’d “protect our access to reproductive health care.”

Ultimately, Rombeau won by 37 votes. And many Democrats are coming around to the idea that if they’re going to really counter abortion bills like the one in Texas, their best remaining option is to replicate Rombeau’s win in hundreds of legislative districts around the country come November 2022.

That will require a major strategic shift for the Democratic Party: It would actually have to invest in campaigns to win state legislatures.

Over the last decade, Democratic donors and grassroots supporters have poured their firepower into winning federal races with a fair bit of success. But they’ve habitually neglected fights for state capitols, and the results speak for themselves: today, the GOP controls 30 of 50 state legislatures, and over 55 percent of all state legislative seats nationwide.

Now, Democrats might control the White House and own majorities in Congress, but the court’s decision makes clear they are essentially powerless to push back from Washington on GOP state-level abortion bills.

Many in the party believe that the events of the last week are a clear consequence of the party ceding so many states to the GOP. And they’re loudly saying it should serve as a wake-up call to seriously rebuild their state-level power before it’s too late.

One DLCC staffer, Christina Polizzi, tweeted after the Texas abortion ruling that she was “literally begging” for Democrats to finally care about state-level races. It racked up over 7,000 likes.

The DLCC’s executive director, Jessica Post, told The Daily Beast that they need to “more than double our organizational budget” in order to make real gains on the state level in 2022. That would entail raising more than $100 million.

“The reality is, a Democratic trifecta in Washington doesn’t mean we can hang a ‘mission accomplished’ banner across the country,” Post said in an interview. “One thing we know for sure as Democrats is that the federal government is not coming to save us—abortion rights, voting rights, are going to be decided in states.”

A small cohort in the party has been banging that drum for years, shouting to anyone who’d listen that there’d be repercussions for Democrats’ hemorrhaging state legislative seats over the last decade. (Democrats lost nearly 1,000 state seats during Barack Obama’s two terms.)

These voices have grimaced as Democrats failed, election after election, to heed those lessons. Every state-level operative who spoke to The Daily Beast invoked Amy McGrath, the Kentucky Democrat who has become something of a symbol for the party’s misguided priorities. Last year, McGrath raised $96 million—nearly twice what the entire DLCC brought in—on her way to a 20-point defeat at the hands of Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY).

Among some Democrats, it’s simply gospel that big donors and grassroots supporters alike have a weakness for the exciting “shiny object”—typically, a compelling candidate taking on a nationally hated figure—as opposed to comparatively snooze-inducing state house races.

“Building that infrastructure is hard, it’s very granular, and it’s not sexy,” said David Turner, communications director for the Democratic Governors Association, the other prong of the party’s efforts to win state-level control. “I think Democratic donors sometimes lose sight of the fact that these less flashy races can have an enormous impact.”

Within the party, there’s a deep sense of anger that it’s come to this, and there’s frustration that chatter about eliminating the filibuster or expanding the U.S. Supreme Court in order to protect abortion rights is getting more airtime than calls for investing in state campaigns.

“We wouldn’t have to give so much of a fuck about the Senate if we had won state legislatures… The bad laws start in these chambers,” said Amanda Litman, founder of Run For Something, a progressive group that supports candidates for local offices. “I sometimes feel like I’m going a little crazy, because I’ve been saying this for four years and counting.”

All agree, however, that any effort is better late than never.

“As Democrats, we just do not understand state power,” Post said. Texas, she added, has offered “a “really tough way to learn a hard lesson about the importance of state-based power. I hope as Democrats, this is something we start to understand, invest in, focus on appropriately.”

Depending on which Democrat you ask, the party is either a few election cycles or more than a decade behind the GOP when it comes to their ability to win state-level elections. Nearly all trace that to the first two years of Barack Obama’s presidency, when Republicans—shut out of power at all levels in Washington—made a concerted, unprecedented investment in winning state-level races so that they could then draw more favorable congressional maps during the once-in-a-decade redistricting process.

The plan worked. The GOP won a whopping 680 seats nationwide and flipped 19 state legislatures. And the gerrymandering Republicans executed in many states only solidified their 2010 gains, putting them on structurally advantageous turf for the next decade.

Republicans now have archconservative majorities not only in places like Texas, but in a number of states Joe Biden carried, like Georgia, Wisconsin, Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. In some of them, the balance of power in legislatures is lopsided in the GOP’s favor: 60 of Wisconsin’s 99 state legislative seats, for example, are held by Republicans.

Faced with structural disadvantages, many Democratic donors checked out even further from state-level campaigns, and the GOP has consistently outraised and outspent Democrats on this front. In 2018, the DLCC had a record-breaking fundraising haul of $32 million, while its counterpart, the Republican State Leadership Committee, raised $45 million, according to campaign finance tracker OpenSecrets.

In total, all Democratic candidates for state legislature nationwide raised more in 2020 than GOP candidates did. But Democrats were outgunned in most of the states they were targeting to flip, according to records from another tracker, FollowTheMoney.org. In Georgia, for example, GOP candidates raised a total of $83 million compared to Democrats’ $32 million.

Republicans argue that increased Democratic investments won’t dent their dominance. The last election in 2020 may have been a record fundraising year for Democrats, but the results were disappointing, with the party losing two chambers even as they swept to power in Washington.

Andrew Romeo, a spokesperson for the RSLC, said in a statement to The Daily Beast that state-level Democrats “clearly haven’t learned from their disastrous 2020 cycle.”

“State Republicans will be successful in 2022 because they continue to focus on common-sense policies that are best for their constituents rather than trying to mirror the dangerous ideas coming out of Democrat-controlled Washington,” Romeo said.

The stakes for Democats’ state-level struggles stretch far beyond abortion rights. Numerous states controlled by Republicans have advanced laws that restrict avenues to the ballot box—in response to Donald Trump’s defeat and their loss of Congress in the 2020 election—and several state legislatures, most notably Arizona’s, have launched audits of the 2020 election results in last-ditch attempts to validate Trump’s baseless claims of massive election fraud.

In Washington, Democrats have struggled to respond. Faced with unified GOP opposition, their legislation to preempt state-level voting laws in Congress is on ice until or unless Democratic senators change the chamber’s rules to pass it with a simple majority.

State-level Democrats hope that gridlock in Washington and increased attention from the party base on the activities of Republicans in places like Texas and Arizona might finally compel donors to prioritize defeating them.

“These types of laws often drive renewed focus. The question is, will it be sustained focus?” said Turner. “I would have hoped for a wake-up call prior to Texas putting this law in, but because Democratic donors tend to live on the coast, sometimes a shock to the system is required to get them to pay attention to what’s going on in the middle of the country.”

There are some early signs of engagement. Litman said that in the week since the court’s decision on Texas’ law, five times the normal number of people signed up to express interest in elected office through Run For Something.

“We can’t fix the past, but we can decide what to do about the present and future,” Litman said. “We made a mistake, but it doesn’t have to be permanent.”