When he was president, Donald Trump kept promising ambitious infrastructure bills fueled not by piles of taxpayer dollars but a scheme to leverage private funds for public investment—known by policy nerds nationwide as a “public-private partnership.”

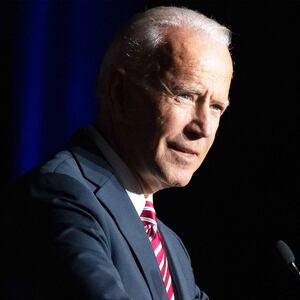

Democrats largely mocked the idea as a gimmick. But now, as they try to make an historic infrastructure package happen under President Joe Biden, some lawmakers who panned the idea during the Trump years are warming to it—or at least aren’t ruling it out.

In the last week, a group of 20 senators—10 Democrats and 10 Republicans—have met daily in hopes of striking a bipartisan deal to create nearly $600 billion worth of new funding for roads, bridges, water, clean power, and more.

In order to get the required 60 votes in the Senate, the group wants to avoid raising taxes to pay for these projects. Instead, they’ve dusted off the public-private partnership: a recently released memo from the group of 20 lists “public private partnerships, private activity bonds, and asset recycling” as leading revenue raisers for their plan.

It’s normal for Democrats and Republicans to compromise on policies and pay-fors when striking a deal. But the hatred that Democrats expressed for this particular proposal is less common.

After his 2018 State of the Union address, full of bullish talk about private investment to fuel Trump’s infrastructure bill, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL) said the idea was a “throwaway” and “avoids coming up with serious funding.”

Durbin is at the negotiating table with the group of 20 this week—but that apparently doesn’t mean he is entirely behind what they’ve identified as a central funding source for their plan. Asked by The Daily Beast if he’d changed his mind on the utility of public-private partnerships, the second-ranking Senate Democrat was still wary of the idea.

“Public-private has got to be watched carefully and closely,” said Durbin, pointing to the recent leasing of Chicago’s public parking meters by a private company. “I’m not ruling it out, but I’m just saying that I come to it with a degree of skepticism.”

Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) is also part of the negotiating group. In 2017, he panned Trump’s proposals.

“I don’t know anybody in the infrastructure business that thinks that tax advantage for equity and public-private partnership deals are what’s going to fix the problem,” he said then.

But asked on Wednesday if such a mechanism would be part of the bipartisan group’s deal, Warner responded that it was a “great idea” before heading into the Senate to vote.

Another group member, Sen. Jon Tester (D-MT), said in 2018 that the public-private partnership structure didn’t make much sense for funding projects in rural areas, like those in his home state of Montana. His office did not respond to a request for comment on Tester’s views now.

Most Democrats strongly believe—and have for the last four years—that direct federal dollars are the most effective way to finance a broad infrastructure package. Some support such investment schemes on specific infrastructure projects, like extending high-speed internet to rural areas.

But many Democrats are puzzled that the party isn’t outright rejecting a deal that would incorporate public-private partnerships to carry much of the weight in a multi-hundred-billion dollar infrastructure plan.

“Trump tried this. That is not a real thing,” said Rep. Jared Huffman (D-CA), a member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee. “That was going to give us new golf courses and private infrastructure, and not the stuff that is hard to finance and that the public actually needs.”

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) told The Daily Beast that the public-private partnership proposal has “flown under the radar” and called it a “trap” that gives lawmakers a way out of taxing the wealthy. “Then, it ends up being a tax on the working and middle class,” Ocasio-Cortez said. “We cannot allow that to happen.’

And Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) said it was a “bad idea. Period.”

It’s unclear what, if anything, will come of the group of 20’s negotiations. Its fortunes seem to rise and fall by the hour on Capitol Hill. On Wednesday night, some senators emerged from a dinner meeting and indicated they’d reached agreement on a framework for legislation, which they’d be taking to Biden for a White House meeting on Thursday.

But the fact that the only current path for a bipartisan deal has, as its core, an idea that much of the majority party thinks is laughable speaks to just how challenging it could be to cobble together a bill that can get 60 votes in the Senate.

“I’m disappointed that as far into the process as we are, that’s what you see when we peel back the onion?” said Huffman. “I mean, that’s just nothing.”

The bipartisan group has yet to specify just how much of their proposal would be fueled by private dollars. But it’s unlikely that the entire package would hinge on the private fundraising path, as Trump’s did.

Democrats and Republicans have proposed tapping into other pots of funding, like unspent COVID relief money and unused unemployment insurance, funds to pay for the package. Beefing up the IRS to ensure there are fewer tax cheats is another popular fundraising method. Trump’s team, by contrast, floated vague schemes like fronting $200 billion in federal cash to somehow get $1 trillion in private investment, which never made sense to many Democrats.

They see unions of public and private cash as most effective when targeted to specific projects—like high-speed rail in the Pacific Northwest, for example.

Lawmakers say that the group of 20 is hammering out how much they could realistically raise through public-private partnerships. Durbin admitted they would have to be a central part of paying for any bipartisan plan, however.

“If you listen to Warner, God bless him, he gives various estimates of what it’s worth,” Durbin said on Wednesday. “I’ll trust his judgment on it, but I’ve told him my reservations.”

Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY), meanwhile, has avoided commenting on the specifics of the bipartisan group’s negotiations as he aims to maintain two possible avenues toward an infrastructure bill: a deal based on what they come up with, or a broader package that could pass with only Democratic votes.

But Schumer didn’t avoid sharing his thoughts on a public-private partnership-driven package in 2018. The then-Minority Leader said that mechanism amounted to “private-sector gimmicks and giveaways” that would inevitably lead to tolls. And then he trotted out a clever bit of branding he was never able to use: “Trump tolls.”