If there’s proof that there is a silver lining to every cloud, it may be in an exhibition of Dennis Hopper’s work as a photographer during the 1960s.

Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album, opening Thursday at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, showcases 400 vintage photographs that the Easy Rider director took during what might be considered his lost years. From 1960 to 1967, Hopper disappeared from Hollywood, and this trove of images helps document how he spent his time.

They also kept him alive.

“I never made a cent from these photographs. They cost me money but they kept me alive...They were the only creative outlet I had for these years until I made Easy Rider. I never carried a camera again,” reads a Hopper quote typed out on the wall.

Once a hot young star who signed with Warner Bros. at the age of 18, Hopper lost his contract with the studio after a row with the director Henry Hathaway on the set of From Texas to Hell in 1958. He didn’t return to his first love, filmmaking, until 1967 when he started work on the 1969 release of Easy Rider, a movie that helped herald in a new era in filmmaking dubbed “The New Hollywood,” where filmmakers like Hopper did things their own way.

Easy Rider explored aspects of the new counterculture that had emerged in the 1960s, and showed how it was possible to make low-budget films guided by a new aesthetic far removed from polished studio films. But that wasn’t Hopper’s only success during this time period. The Lost Album photographs prove that the filmmaker was just as original and raw when it came to still life.

He discovered his passion for photography through James Dean, who he worked with on Rebel Without a Cause.

The photos, which constituted his first show, were originally shown at the Fort Worth Art Center in Texas in 1970, and all but disappeared until they were discovered in his garage after his death in 2010.

What was uncovered between the boxes of Christmas tinsel in his garage in Los Angeles was a documentation of the cultural upheaval of 1960s America, from the civil rights movement to hippies, from pop art to the Beat poets and Hollywood, groups at both ends of the extreme.

Images include those of a famous civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama in 1965, which marked the high point of the movement and led to the 1965 Voting Rights Act outlawing voting discrimination. Among Hopper’s photographs is one of Martin Luther King Jr. making his famous speech.

The photographs were taken at a time when America was in both social and cultural turmoil, and the frustrated young actor worked obsessively to document the changes unfolding around him.

Hopper was also very interested in what was taking place in the art scene. He took stock of some of the key protagonists on the West Coast as well as East Coast experimental artists including the dancer Merce Cunningham. He collected art from some of the influential figures of the time, snapping up an Andy Warhol for $75 and building up his collection with works from artists ranging from Ed Ruscha to Roy Lichtenstein and Edward Kienholz. He immersed himself in the art world and photographed artists on the West Coast, like John Altoon and Larry Bell. Ditto on the East Coast, with Robert Rauschenberg, Warhol, and Lichtenstein, as part of his documentary of Pop Art.

Some of his photos were commissioned to decorate invitations to the top galleries of the day—including the Ferus Gallery, a key meeting place in the Los Angeles arts scene—which led him to get assignments as a photographer for major magazines like Vogue.

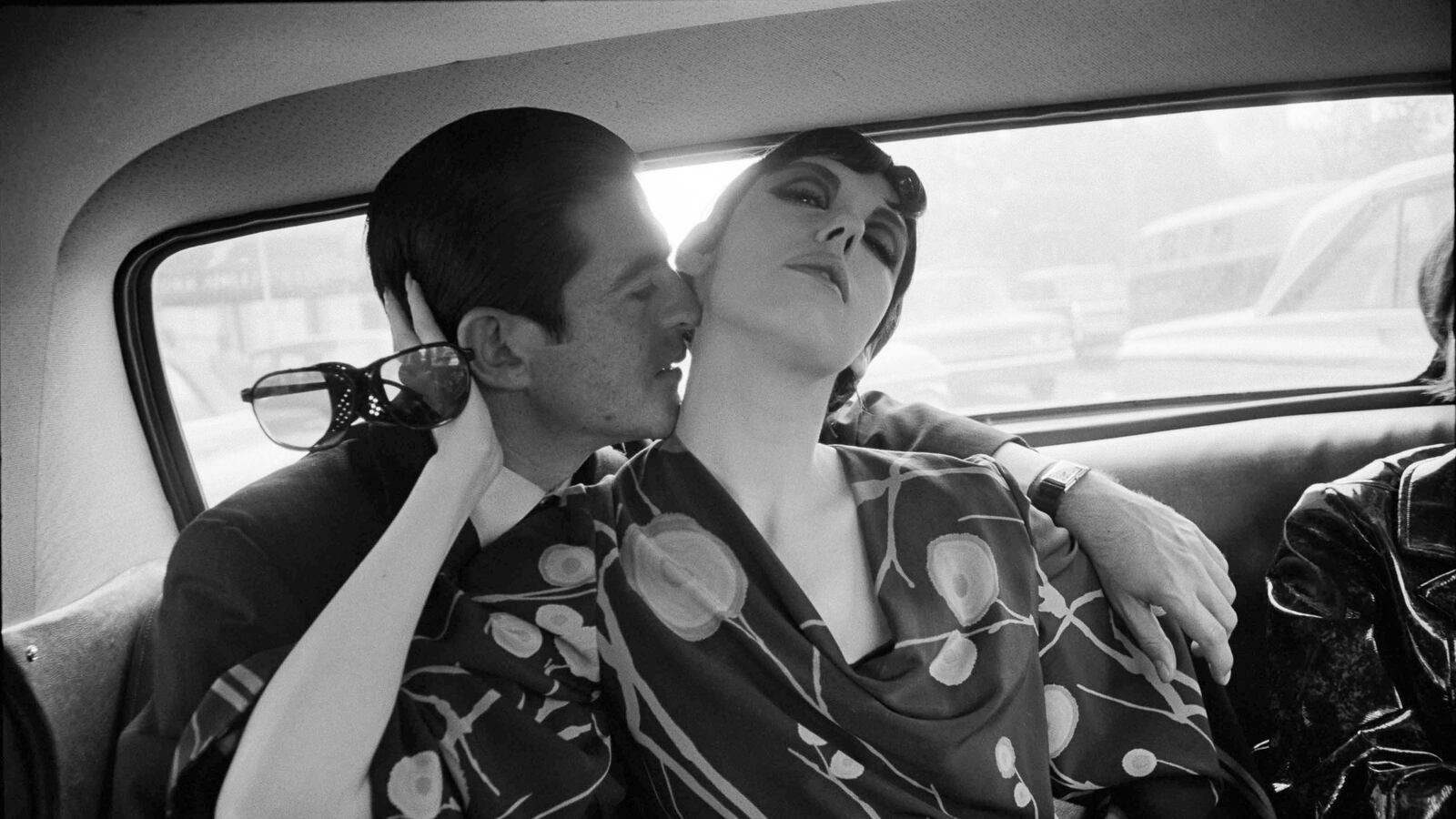

Hopper also knew pop stars and created an album cover for Ike and Tina Turner. He photographed his friends, like Jane Fonda and Paul Newman, taking candid shots of the icons of the day.

Alongside pop artists, Hopper documented the Beat poets and hippie gatherings like Human Be In in San Francisco and Love-In in Los Angeles. He shot images of Timothy Leary, a psychologist and psychedelic drug enthusiast whom Nixon dubbed “The Most Dangerous Man in America.”

Before he put them in Easy Rider, Hopper loved bikers and thought of them as the cowboys of the 1960s. A series of photographs show another movement of sorts—the Hells Angel at work. Clashes resulted in deaths when the group was hired as security for a Rolling Stones concert in 1969, marking the beginning of the end of the idyllic spirit of the 1960s.

RELATED: Dennis Hopper: ‘The Lost Album’ (PHOTOS)

Hopper even photographed his television screen to show current events. As the exhibition’s curator, Petra Giloy-Hirtz, puts it, the images represent “an album of his time.”

“He embraces the entire universe and, when he could not be there, he photographs the television, which seems fitting that he would capture the world in that way,” Giloy-Hertz says.

As a photographer, Hopper had his own abstract, almost street photography, style. Rather than playing to stereotypical ideals of glamour, sun-drenched, poolside notions of Los Angeles, or rockers high on cocaine, Hopper’s photos have an abstract, almost gritty and more serious feel. They look like art.

When Hopper took photographs of his famed contemporaries, he seemingly stripped them of their glamorous aura, presenting real folks living their real lives.

“Newman even looks pensive in his shot,” said the Royal Academy’s head of exhibition management, Andrea Tarsia, of a no-nonsense shot of the actor sunbathing on the beach.

Andy Warhol is pictured with David Hockney, Jeff Goodman, and Henry Geldzahler, posing like a group of worker bees in suits and ties. Jasper Johns stands tall like a figure from The Great Gatsby in a casual suit. Robert Rauschenberg is photographed like a schoolboy prankster with his tongue poking out.

When the images appear stylized, it seems to be by default. The photographs look spontaneous and intimate, capturing the subjects off guard or in close-ups, almost like selfies.

While Hopper did photograph neon signs and other Americana, like other artists of his time, his photos never look showy; rather, they capture passing moments of the world in which he lived.

The 4th of July is depicted as an American flag stuck into the sand of a desolate beach in Malibu, with a rifle placed in its grains. The image is one of a number of artsy, minimalist shots showing things like paint dripping down a fence or the fragile silhouette of an animal in a cave painting.

The poster image of Melrose taken through the front screen of a car window, helps visually sums up the style of this body of work—Hopper shows his view of the city and the world around him as it unfolds each day.

“It is a virtual dictionary of the cityscape of Los Angeles,” Tarsia says. “He looks at the city with the eyes of an artist, and an abstract artist at that.”

Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album is on display at the Royal Academy of Arts from June 26 through October 19.