While the world watched Minneapolis cop Derek Chauvin pin George Floyd to the ground by the knee for more than eight minutes last May, Amity Dimock was still awaiting answers about the death of her own child at the hands of Minnesota police.

In August 2019, her son, Kobe Dimock-Heisler, was shot six times by two Brooklyn Park police officers responding to a “disturbance call” at his grandparents’ house. The 21-year-old, who was on the autism spectrum and had a history of mental illness, had lost his temper and eventually turned his anger on his grandfather, Erwin Heisler.

Fearing for his grandson’s safety, Heisler called the cops. By the time two officers arrived, Kobe had calmed down, so Heisler tried to send them away, but they forced themselves inside anyway, the grandfather said. During a tense conversation in the living room, Kobe lunged for something hidden in the couch cushions. Officers later said they thought he was grabbing a knife—and responded by shooting him three times in the chest and neck.

“They shot him in the head. In front of his grandmother,” Amity Dimock, a 47-year-old accountant, told The Daily Beast. “It was the worst day of my life.”

On Aug. 5, nearly a year after the young man’s death, the Hennepin County Attorney’s office announced they would not file charges against the two officers who shot him. It took the same prosecutors just four days to charge Chauvin in Floyd’s murder amid a nationwide outcry.

“It’s beyond frustrating. My son’s case was just sitting on Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman’s desk while they hopped, skipped, and jumped over it to prioritize George Floyd’s case,” Dimock added. “When George Floyd died, he was all over the news. Celebrities, reporters, even politicians were saying Floyd’s name. I just kept thinking, ‘Why aren't they also saying my son’s name?’”

Dimock is just one of the hundreds of Twin Cities residents who have lost loved ones at the hands of local law enforcement in the past two decades. Now, they are focusing their attention on Chauvin, one of the four officers fired for his involvement in Floyd’s May 25 death.

“For so long, hundreds of people have been brutally murdered by police officers in Minnesota,” Toshira Garraway, who founded Families Supporting Families Against Police Violence after her fiancé was killed by cops, told The Daily Beast. “All of these families are worked up right now and they are scared because we are just hoping for once in our life we can see justice with Derek Chauvin’s conviction.”

On Monday—less than a year after a video of Floyd’s death went viral—the former Minneapolis police officer’s long-awaited trial was set to begin in a Hennepin County courthouse. The high-profile case is now in the hands of the Minnesota Attorney General’s office, after a judge banned Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman and his staff from the case in September, citing their previous “sloppy” work.

Chauvin faces two charges, second-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter, for violently arresting Floyd over a counterfeit $20 bill. He faces up to 40 years in prison.

But on Monday, jury selection was delayed after the Minnesota Court of Appeals on Friday ruled that the previously tossed third-degree murder charge against Chauvin should be reinstated. During a Monday hearing prior to jury selection, which was scheduled to roughly take three weeks, Hennepin County Judge Peter Cahill, who ruled against the third-degree murder charge last year, said he wanted to hear from the state Court of Appeals about whether the new charge could be added to Chauvin’s case. Prosecutors agreed with the delay, stating any logistical loose ends in the case before the trial could result in grounds for an appeal.

Chauvin’s defense attorney, Eric Nelson, also said Monday he intends to ask the Minnesota Supreme Court to consider the third-degree murder ruling, which would delay the trial. That appeal could further delay arguments are scheduled to start March 29.

“I want to inform the court that we’re prepared to try this case,” he said. “It is not our intent to cause delay. However, I feel I have an ethical obligation to my client to [petition the Supreme Court].”

At trial, prosecutors will argue Chauvin had his knee on Floyd’s neck for roughly nine minutes—including nearly three minutes in which Floyd was unresponsive.

“Please, please, please, I can’t breathe. Please, man,” Floyd said in the viral body-camera footage, which didn’t show the beginning of the arrest. “I’m about to die.”

EMTs said that he had no pulse when he was loaded into an ambulance. The Hennepin County Medical Examiner concluded Floyd died of cardiac arrest from the restraint and neck compression, also noting that Floyd had heart disease and there was fentanyl in his system. An independent report commissioned by Floyd’s family concluded that the 46-year-old died of strangulation from the pressure to his back and neck. Both reports determined Floyd’s death was a homicide.

Three other officers—Tou Thao, Thomas K. Lane, and J. Alexander Kueng—assisted with the arrest, holding down Floyd’s legs and trying to keep concerned bystanders at bay. They’ve been charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder while committing a felony, as well as aiding and abetting second-degree manslaughter with culpable negligence, and are expected to face a trial together in August.

“This case will be remembered as one of the most egregious police brutality cases in the history of America,” Ben Crump, a civil rights attorney representing the Floyd family, told The Daily Beast. “This case will be a referendum on where America is on equal justice.”

Chauvin's lawyer, who did not respond to The Daily Beast’s multiple requests for comment, has previously argued that it was not his client’s fault Floyd died—instead blaming it on the other rookie cops who he said should have called an ambulance sooner or “chosen to de-escalate” the situation.

“If EMS had arrived just three minutes sooner, Mr. Floyd may have survived. If Kueng and Lane had chosen to de-escalate instead of struggle, Mr. Floyd may have survived,” Nelson wrote in a September filing. “If Kueng and Lane had recognized the apparent signs of an opioid overdose and rendered aid, such as administering naloxone, Mr. Floyd may have survived.”

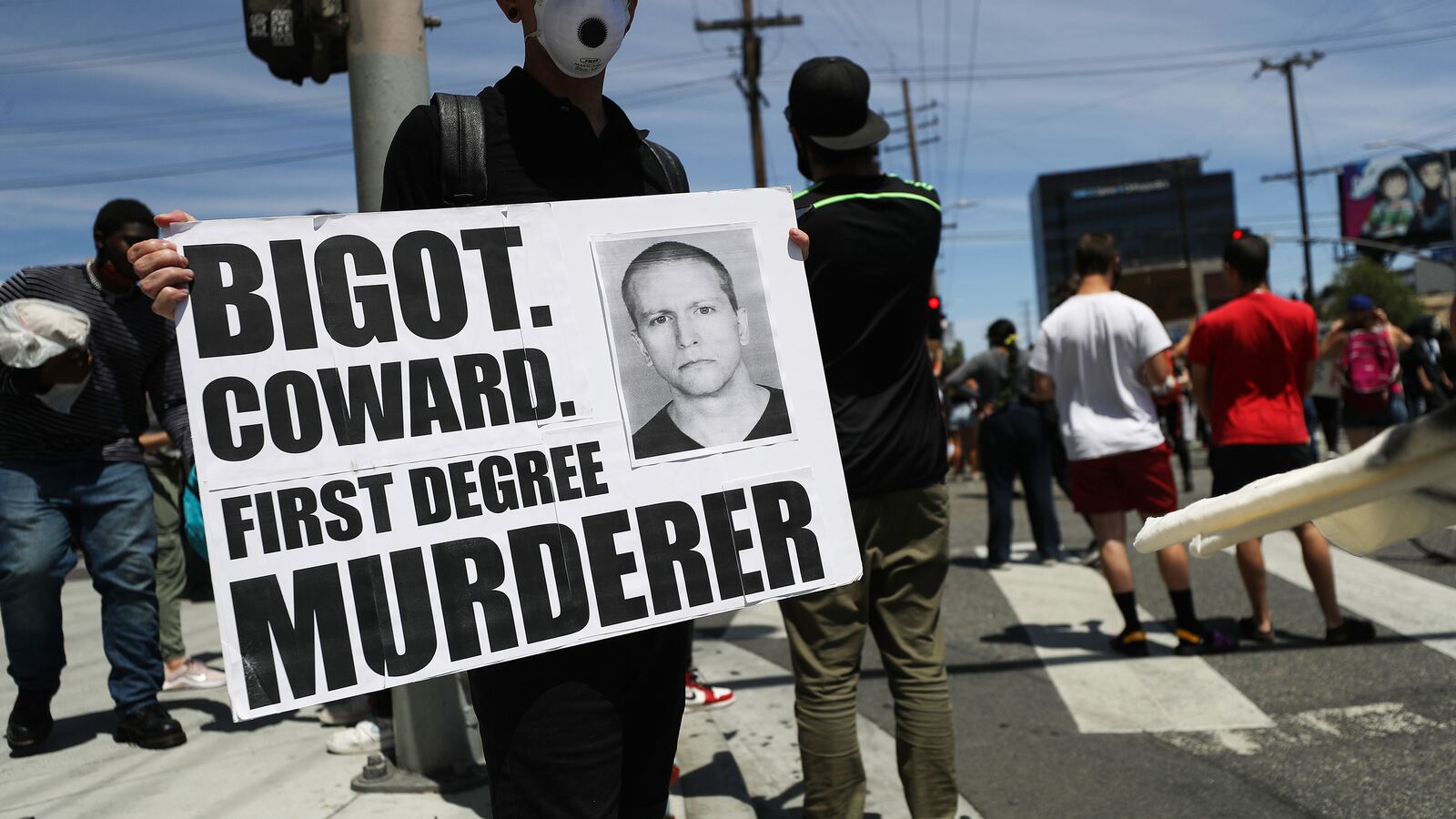

The 10-minute video of Floyd’s death sent shockwaves through social media, erupting the already simmering anger about racial injustice and police brutality in the U.S. and prompting people to take to the streets in protest. Floyd’s final pleas became a rallying cry, bringing renewed energy to the Black Lives Matter movement.

“This case speaks to a larger conversation—and its outcome will have a big impact on public policy to come. This is extremely high stakes,” Mike Lawlor, an associate professor at the University of New Haven and a former prosecutor, told The Daily Beast. “It’s almost like a political event, not just a judicial one because this trial will be a catalyst one way or another.”

Jonathan Smith, the executive director of the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs, said “the prosecution knows the whole world is watching.”

“If they don’t convict, it will be devastating for prosecutors,” he told The Daily Beast, adding that the video of Floyd’s death is “very powerful” and will be for any jury.

But the pathway to conviction will still be an “uphill battle,” Smith warns, because while it is easier to show that Chauvin used excessive force that deprived Floyd’s civil rights, proving it was “willful” is a more difficult challenge.

“Willfulness is the highest intent standard under criminal law,” Smith, a former official in the DOJ’s civil rights division, said. “To do so, prosecutors need to prove Chauvin actually knew that he was going to violate someone’s rights and acted with purpose. Chauvin’s behavior on camera, though, is going to help the prosecution. He was mocking people who were taping the video and that is powerful evidence.”

Floyd’s trial could have major implications for how other officers who use deadly force will be dealt with since there are so few police brutality cases that actually make it to trial.

“There really isn’t precedent here,” Smith, who also led the independent investigation into Elijah McClain’s death in Colorado, added. “So while it’s a win that this case made it to trial, that means it's a bigger hill to fall if he gets an acquittal.”

There are many who fear that outcome, like Ira Toles, one of several people who has accused Chauvin of brutally attacking them in the years before Floyd’s death.

“I might have to take justice into my own hands,” Toles said, noting he has been denied the justice he deserves for over 13 years.

According to Communities United Against Police Brutality, 10 complaints were filed against Chauvin in his 19 years with the police, but he only ever received two verbal reprimands. The city’s Civilian Review Authority, which lists complaints prior to September 2012, also shows five more were filed against Chauvin—and all closed without discipline. Violent incidents in Chauvin’s past included the 2006 fatal shooting of 42-year-old Wayne Reyes and the 2011 non-fatal shooting of a Native American man.

As previously reported by The Daily Beast, Chauvin barged into Toles’ home unannounced during a 2008 domestic violence call and beat him up in the bathroom—before shooting him in the stomach. Toles, then 21, blacked out during the assault and collapsed at the front door, where he remained bleeding until paramedics came. While Toles pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge, Chauvin continued his career with nothing more than a slap on the wrist.

“He tried to kill me in that bathroom,” Toles said in May.

He’s skeptical of real change coming from Chauvin’s trial. Toles told The Daily Beast last week that it won't immediately change a criminal justice system that seems to disfavor minority communities.

For Garraway, the founder of Families Supporting Families Against Police Violence, the uniqueness of this case also provides a rare national spotlight on Minnesota—a state with “a major problem” with police brutality. Among the countless other cases she says have gone unnoticed is the death of her fiancé Justin Teigen, who was killed by St. Paul police after a traffic stop in August 2009.

According to police reports, Teigen fled from officers during a traffic stop and crashed his car before trying to run away on foot. Hours later, he was found in a nearby garbage bin. The medical examiner and police say he died of asphyxia due to mechanical compression by a recycling truck that he’d been hiding in. Garraway believes that police beat him up before dumping him in the trash.

Now, 12 years later, she works with other families who have lost their loved ones to police brutality in Minnesota. But while she hopes Chauvin’s trial shows the world that police brutality “is not an isolated issue in Minnesota,” she isn’t confident jurors will hold the ex-cop accountable.

“Even if they do give justice for George Floyd, it may be only because politicians are scared of the aftermath,” she said. “Not even because it’s the right thing to do. But because this is the first time that it has spiraled out of control.”

“Chauvin is a white man who killed a Black man and when the Constitution was written—that wasn’t a crime,” she added.

The high stakes of Chauvin’s trial are especially felt by the Floyd family, who are anxious about getting justice for their loved one—and hopeful about what it could mean for police reform and Black Americans across the country, Crump said.

“All eyes are on the prosecutors,” he added. “History has taught us that when a police officer kills a Black person—not much happens. But we’re confident the video and witnesses who saw George Floyd’s death are enough for a conviction.

“And if we don’t get one: I would expect there will be a global outcry,” he added.

The trial is taking place just as the Minneapolis City Council is about to consider a proposal that would dramatically overhaul how the city handles public safety.

In the wake of Floyd’s killing and the protests and riots that followed, nine City Council members joined a rally in Powderhorn Park and pledged to dissolve the police department, replacing it with a new “model” to be determined over the next year.

That effort was derailed in December when the Charter Commission, a committee appointed by a judge to oversee any changes to the city’s charter or constitution, determined by a vote of 10-5 that the council had acted too soon to place the issue before voters on last November’s ballot.

Smaller reforms that activists had pushed for did come to pass: The city banned chokeholds, overhauled the police use of force policy by requiring officers to consider alternatives, prohibited officers from engaging in car chases for minor offenses, and more than doubled the funding for the Office of Violence Prevention, the kind of social program activists argue is underfunded compared with police budgets. (According to The Star Tribune, The Office of Violence Prevention went from a budget of $2.5 million to $7.4 million, while MPD’s budget stands at $164 million).

But the debate over police reform has come as Minneapolis, like many major cities, experiences a surge in violent crime and homicides, dividing community groups and residents. Some see the crime wave as a reason to support more police funding, others point to Floyd’s death and the department’s troubled history as reasons to consider alternatives.

In late January, three council members introduced a new proposal to change the city’s charter, again eliminating the police department, but this time replacing it with a broader public safety department that would include police but also violence prevention programs, mental health services, and specialized response for unsheltered people. The proposal went to a committee hearing on Thursday and would need to pass the full council and a Charter Commission review before going to voters—though the commission could not delay it from going to the ballot.

The timing of the proposal being introduced just before the trial was coincidental, but Councilmember Steve Fletcher, one of the three who introduced it, told The Daily Beast that the trial is “stirring up a lot of emotions.”

“As the city where George Floyd was killed we have an obligation to move deliberately and with intention and persistence to change the system, and we are continuing to move forward at every opportunity to create the kind of transformation that our community is demanding,” he said.

Activists who support the proposal aren’t just counting on the council to pass it. In a parallel effort, a coalition of groups is running a campaign to gather enough signatures to get a similar proposal—one that would also replace the police department with a broader public safety department—on the November ballot. If the petition effort is successful, the council members have said they will drop their effort to avoid overlap.

For D.A. Bullock, a spokesperson with Reclaim the Block, one of the key groups that organized protests after Floyd’s killing, the proposals are the culmination of years of police killings and protests in Minneapolis.

“The charter proposal to create a new public safety department is just a logical acknowledgment of the general public belief that we cannot go back to what brought us to the murder of George Floyd,” Bullock said.

“The Minneapolis Police have proven time and time again that they can not be trusted with exclusive responsibility for our public safety.”