Descendants of people who suffered or died in the Tulsa race massacre have refused to let the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s denial of reparations deter them, and their hunger for a fight has only intensified.

Now, descendants and their allies want recognition in the form of a national monument so the country can never forget or attempt to suppress the brutality that was unleashed on the Greenwood community over a century ago, an event whose effects still linger in the livelihoods of residents and later generations.

“A national monument is the highest designation that a community in a geographical area can attain,” Tulsa race massacre descendant Dr. Tiffany Crutcher said. “It stems from this conspiracy of silence. It stems from us being robbed, of being able to learn what happened because our great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents had to keep this [pain] internalized.”

In an interview with The Daily Beast, Crutcher, a leading voice in the social-political action realm throughout Oklahoma, said she firmly believes that “history is the gateway to truth.”

“If we can acknowledge the truth, then we can repair the harm,” she said. “We have not achieved this atonement or restitution or any repair. Preserving this story will at least start to get us on this path to achieving true justice, true repair, true recognition.”

Crutcher said a monument would help African Americans learn more about their complex history. Multiple properties in Greenwood have been dedicated as historic places, and a park has received support to be added on the Civil Rights Trail. But Crutcher believes that’s not enough. She wants the entire area to be remembered.

“We have to continue to elevate our voices and demand that this story never be forgotten through the designation of this monument,” Crutcher said. “The [Greenwood] survivors, the descendants, we are demanding that Congress and that the Biden-Harris administration take action. The survivors, this designation won’t give them the solace that they deserve, but it will give them a little bit of solace. It would at least acknowledge and say, ‘We see you.’”

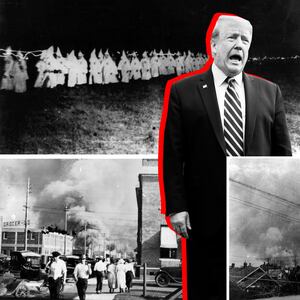

After the Tulsa race massacre on June 1, 1921, in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Library of CongressThe initiative has taken nearly 20 years because Crutcher said there have to be land studies, Congress has to show interest, activists have to appeal to both the National Park Services and the Department of the Interior, and there has to be a “rigorous” engaged community effort.

Finally, in 2023, Sens. James Lankford (R-OK) and Cory Booker (D-NJ) co-sponsored a bill to officially transform Greenwood, also known as Black Wall Street, into a national monument.

“There is established the Historic Greenwood District—Black Wall Street National Monument in the State of Oklahoma as a unit of the National Park System to preserve, protect, and interpret for the benefit of present and future generations resources associated with the Historic Greenwood District, Black Wall Street, and the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 and the role of each in the history of the State of Oklahoma and the United States,” the bill states.

“Now, it’s the Biden administration who’s in the hot seat, and we’re demanding that they act,” Crutcher told The Daily Beast. “President Joe Biden came to Tulsa, the first sitting president to come to Greenwood and give a speech and acknowledge that white supremacy is the biggest threat of our time and to acknowledge what happened here. But now, we have to move beyond words and take action.”

In a statement to The Daily Beast, Booker said the destruction of Greenwood was “one of the worst incidents of racial violence in [U.S.] history.”

“Even the darkest chapters of American history deserve to be told,” he said. “It’s imperative that we act now to ensure that future generations remember Greenwood’s heartbreaking history and its legacy of unrelenting resilience. Establishing a national monument here will forever enshrine this community’s legacy of sorrow, strength, and hope into the fabric of America’s story.”

On May 31, 1921—during an era of prominent Jim Crow and racial segregation, a young Black shoeshiner, Dick Rowland, was accused of assaulting a white teenage girl in Tulsa and arrested. Though there was no proof of the alleged assault and Rowland’s charges were later dropped, a white mob had cooperated with Tulsa-area police to grab him from the jail for a public lynching. Black residents tried to intervene and rallied together at the jail in an effort to protect Rowland, something that Crutcher said showcased just how much love the Black community had for one another.

“You see, they loved the shoeshine boy just as much as they loved themselves, just as much as they loved the prosperous business owners,” Crutcher noted. “That is one of the greatest love stories.”

Smoke billows over Tulsa, Oklahoma, during the 1921 race massacre.

Library of CongressDuring the commotion at the jail, a gunshot was fired in the crowd and Black residents were immediately under attack. Businesses were set on fire, homes were razed, and white vigilante groups were given the power to police all Black people in the area. Black survivors were forced into makeshift internment camps the city designated to house them. They were not allowed to leave without permission.

About 300 people were killed, and unmarked mass graves continue to be found. Hundreds of Black residents were injured, many left homeless, and Tulsa’s Black neighborhood, Greenwood, became a blighted community that still sits in despair. More than $27 million in property damages was never reimbursed by insurance companies.

“My family’s history was stolen from me because they were forced into silence,” Crutcher told The Daily Beast, explaining that her family never discussed what happened. So, she never knew about the brutality unleashed upon Greenwood until after classmates in college asked her about what her family endured. “I didn’t get a chance to sit at my great-grandmother’s feet and ask her about this.”

Crutcher explained that survivors of the race massacre were too afraid to talk about what happened.

“For decades, they dealt with that internalized trauma and grief because they were told that if they ever spoke about it, they would be lynched next. They would be killed.”

Crutcher said her paternal great-grandmother managed to “barely escape the racial terror” by hopping in the back of a neighbor’s truck.

Entrance to refugee camp on the fairgrounds, Tulsa, Oklahoma, after the Tulsa race massacre of June 1, 1921.

Library of Congress“It’s not just about Tulsa. Tulsa is the microcosm of what’s happening,” Crutcher said of the proposed monument. “We have to understand that 10,000 people were displaced and had to flee from Tulsa as refugees across state lines. There is a Greenwood diaspora. People are everywhere.”

With only two living survivors of the massacre—Viola Fletcher and Lessie Benningfield Randle, Greenwood activists appeared at the Oklahoma Supreme Court to make arguments for reparations. However, the court dismissed the case in June.

American businessman John Wesley Williams sits in his car with wife Loula Williams and their son, WD Williams, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 1910s.

Greenwood Cultural CenterGetty ImagesStill, Crutcher is bound and determined to make Greenwood’s tenacity live on.

“We want to make sure that this spirit never dies, that this legacy never dies,” she said.

“Greenwood is one of the greatest love stories… They built something out of sheer will and determination, one of the most prosperous economic enterprises. They cared for one another. They shared resources. It was a community woven together in kindness and love. And if we can preserve this story and get this national monument, people can learn about where they come from.”