Assassins’ bullets have carried off four American presidents. But only two of the unfortunates continue to command the lion’s share of attention from popular writers, scholars, filmmakers, and, not least, conspiracy theorists. Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy scarcely require introductions. In significant respects we continue to mourn these men, as if by doing so we might keep alive what is finest about America when confronted daily by what is ugliest.

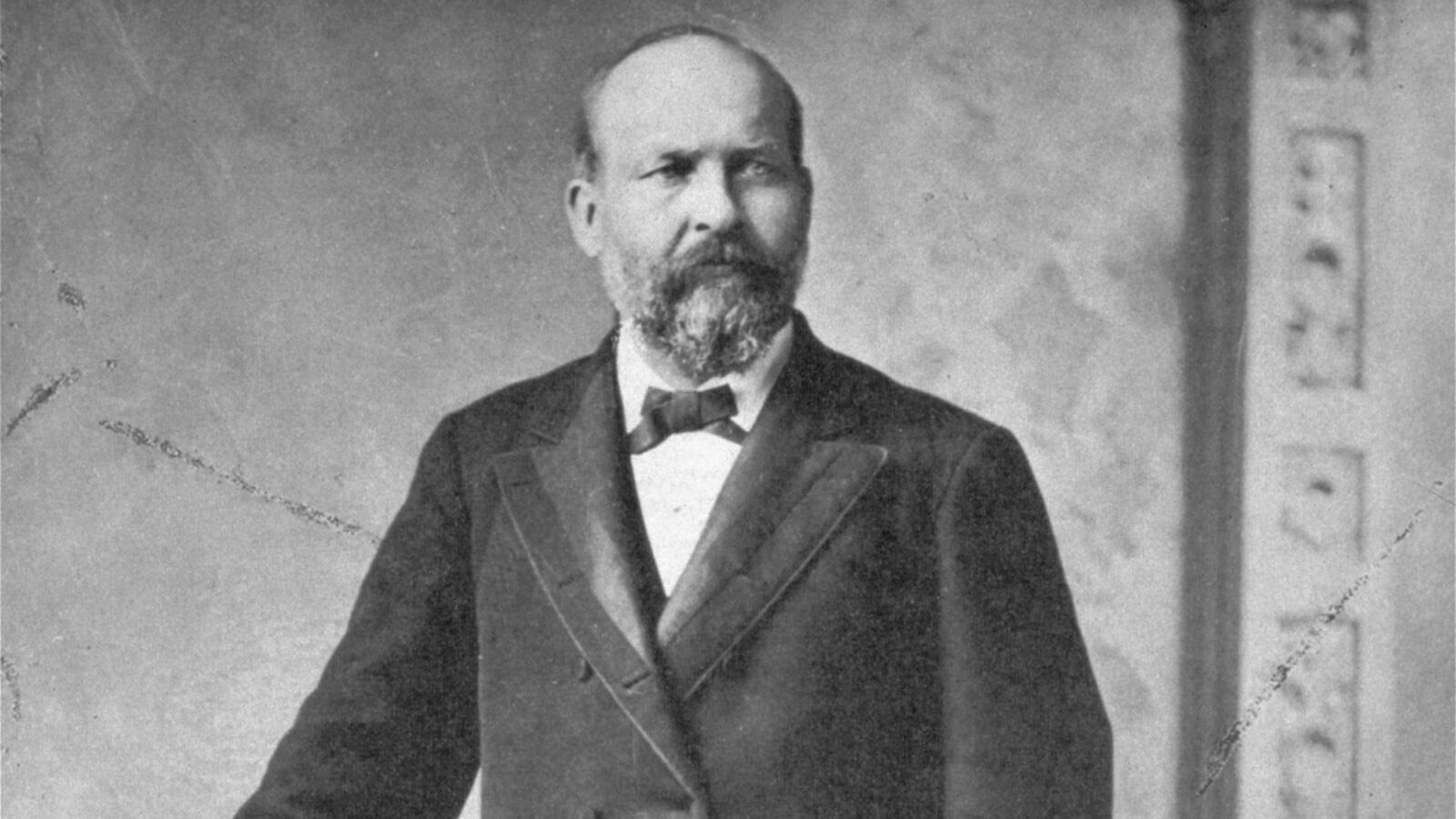

In her brilliant and absorbing new book, Destiny of the Republic, Candice Millard makes a persuasive case for elevating a third martyred president—America’s 20th—to the pantheon long reserved for Lincoln and Kennedy. Forty-nine-year-old James A. Garfield served fewer than 200 days in office before being gunned down in July 1881 by an “unhinged” man named Charles Guiteau—a frustrated office seeker and two-bit lawyer who credited himself with orchestrating Garfield’s unsought victory at the Republican National Convention, in 1880. (Guiteau’s claim was more than a touch delusional, although, in fact, he’d written a minor speech championing the progressive and reformist Garfield over Ulysses S. Grant, a machine politician and two-term president set on a comeback.)

Garfield has not been entirely neglected by presidential biographers, one of whom—Alan Peskin—Millard praises as his “definitive” life chronicler. Destiny of the Republic, then, concerns itself only in the broadest sense with the conventional details of Garfield’s ascent to the national stage and his tragic, untimely demise. As in her best-selling River of Doubt, which took readers deep inside Teddy Roosevelt’s harrowing journey into the Amazon, Millard settles here on a story all but lost in the cavernous house of presidential history. Equal parts political and medical thriller—indeed, a dazzling cross between the best of Robert Caro and Robin Cook—Destiny of the Republic offers a bristling account of the dramatic struggle to save Garfield’s life. A struggle, Millard explains, inextricably bound up with larger, fiery contests over America’s post–Civil War future and over the trajectory of modern science and medicine.

Unlike Presidents Lincoln and Kennedy, both of whom died within hours of being shot, Garfield lingered for two-odd months in a White House bedroom, tended by physicians stubbornly resistant to Joseph Lister’s theory of antiseptic surgery (then widely accepted in Europe). The bacterial infections that killed thousands of Civil War soldiers in unsanitary makeshift battlefield hospitals were largely preventable by the time that Garfield’s surgeons began probing his wound with unsanitized instruments. Although Lister makes periodic appearances throughout Destiny of the Republic, his role is really that of man pleading and shouting from offstage. If the book has a star, apart from the eminently likable Garfield himself, it is surely Alexander Graham Bell, of telephone fame, who within days of the president’s shooting frantically set about making a device—essentially a metal detector—with which to identify the location of Guiteau’s bullet. Bell, to his infinite sadness, never did locate the bullet; incredibly, he’d been instructed by doctors to look on the wrong side of Garfield’s body.

Crowded books with multiple storylines can be difficult to follow, but Millard moves dexterously from scene to scene and character to character, never faltering as she shifts from Garfield’s sickbed, to Bell’s makeshift laboratory, to the Washington courtroom where Guiteau’s lawyers mounted a widely publicized and highly controversial insanity defense.

Destiny of the Republic soars as serious presidential history: it’s intimate and compelling without being shallow. The pages that Millard devotes to the inner workings of the Republican Party on the eve of Garfield’s nomination rank among the book’s finest. No less than John F. Kennedy, who enjoyed an uneasy relationship with Lyndon B. Johnson, Garfield had a competitor in his No. 2 and eventual successor, Chester A. Arthur, a New York senator and Grant loyalist who, as running mate and vice president, undercut Garfield at every turn. Millard proves an eminently clear-headed guide to the treacherous corridors of the late 19th-century Capitol.

Millard is excellent, too, on the everyday details of the presidency: the lack of security (the Secret Service wouldn’t assume its protective role until after the assassination of William McKinley in 1901) and the appalling shabbiness of the White House—a powerful metaphor for the country’s chaotic, precarious state. Indeed, what’s most striking about the presidency in Garfield’s day, as Millard so memorably conjures it, is how little it seems to have changed since George Washington’s day. Garfield’s America was very much a country in its infancy, even a century after the American Revolution.

Garfield might have been forgiven his reluctance to accept the Republican nomination, to say nothing of his strong distaste for the presidency. America in 1880 was still reeling from the Civil War and from Lincoln’s assassination 15 years before. Delightfully unburdened by narcissism but heavily burdened by the demands of what he called “this honor ... unsought,” Millard’s Garfield is impossible not to admire. That he found any success at all seems nothing less than remarkable. That he found himself in the White House defies belief. “Born into almost unimaginable poverty in rural Ohio,” Garfield endured a hardscrabble frontier childhood that makes Lincoln’s seem almost idyllic. “James did not have a pair of shoes until he was four years old,” Millard writes. And yet, against such incredible odds, Garfield became a college professor, a lawyer, a Union Army general, and a U.S. senator. In Congress, Garfield quickly established himself as a vigorously outspoken abolitionist and civil-rights advocate—a man on the side of the angels, opposed to the spoils system that had flourished under Ulysses S. Grant.

And so one sets down Destiny of the Republic entranced by Millard’s considerable narrative powers and, too, more than a little saddened by the death of a remarkable man who might well have helped to mend a grievously fractured nation. We can only speculate, of course, about what Garfield’s legacy might have been. As Millard sees it, Garfield’s death actually helped guarantee the acceptance of Lister’s theory in America. Then, too, there was the matter of national healing—of narrowing the chasm between North and South. As one minister put it, soon after Garfield’s death: “Bound together in one common sorrow, binding in its vastness, we are one and indissoluble."

Perhaps, but only—as history shows—for a time. How heartbreaking that national unity, however tenuous, should depend on the death of a president.