With extraordinary interviews with new sources, William Todd Schultz’s An Emergency in Slow Motion: The Inner Life of Diane Arbus, to be published on August 30th, promises to be an explosive contribution to what’s known about Diane Arbus, whose influence and value in the art world has soared since her death in 1971, at the age of 48.

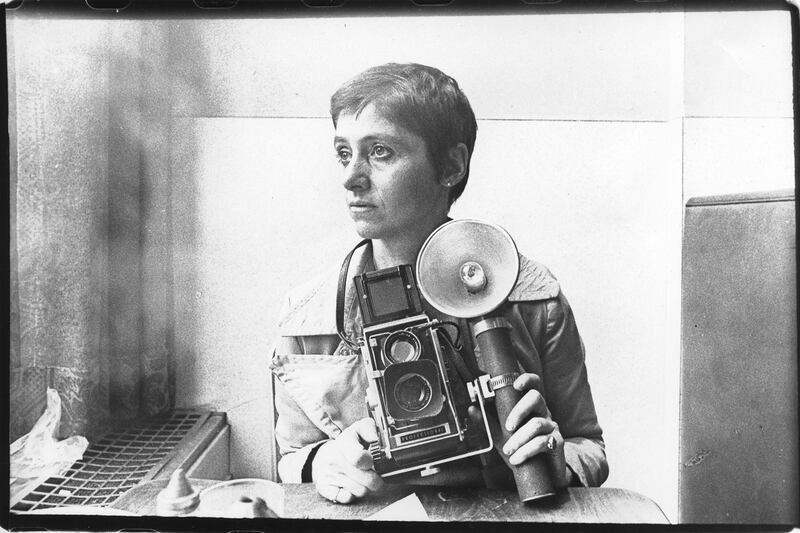

From her iconic photographs of twins, shy swingers, and surly teens in Washington Park to her Coney Island circus acts, Arbus’s work is instantly recognizable: an unflinching yet often strangely lyrical vision of the oddity of normality, and the normality of oddity. But for all the interest in her work, even including a fictionalized portrayal on screen by Nicole Kidman in Fur, the woman herself remains out of focus.

This mystery is precisely what the famously guarded Arbus estate would like to preserve. They have always been adamant that the art should speak for itself. In an afterword to the 2004 book Revelations, Doon Arbus wrote that her mother’s photographs needed protection from “an onslaught of theory and interpretation.” They are, she maintained, “eloquent enough to require no explanations, no set of instructions on how to read them, no bits of biography to prop them up.”

For Schultz though that was not enough. It was as a college student in the early 80s that he first encountered Arbus’ famous freaks: “I remember a girlfriend of mine reading Patricia Bosworth’s book and going downtown and shooting as many weirdos as possible.”

Astonishingly, aside from the authorized material published in Revelations, Bosworth’s 1984 biography is the only major biography to have been published in the thirty years since her death. Schultz is now a professor of psychology at Pacific University in Portland, Oregon, specializing in personality research and “psychobiography.” It’s in this genre that he tries to make sense of what he terms Arbus’s “oceanic” personality.

His idea for his book was to “super-impose the life on the work,” a process that he sees as “mutually illuminating” for both her personality and her work. With his focus on the personality of his subjects, Schultz, who curates a series of books on the “inner lives” of artists, writers and political figures for the Oxford University Press, has unsurprisingly long since been frozen out by the Arbus estate.

As Schultz argues, secrets—their telling, their emotional currency, their exchange—were a fascination that began in Arbus’s childhood and “the dominant metaphor in her life.” To all those whom have wondered “why?” comes the explosive testimony of Helen Boigon, Arbus’s therapist with whom she sought help for depression from late in 1969 to the end of her life on July 26, 1971. In the course of phone conversations with Boigon (who died in 2009) Schultz became the recipient of an extraordinary secret himself. Boigon alleged that Arbus described her older brother, poet Howard Nemerov, as “one of her more intriguing sexual playmates.” Schultz writes, “Arbus seemed, Boigon believed, to be referring to more than just childhood games. The suggestion was that she and her brother had sex. But there was no elaboration, and Boigon never pushed it. The possibility remained, forever, yet another of Arbus’s long-thought-out secrets.”

Given that Arbus killed herself, Boigon’s treatment can’t be regarded as successful, and, as a result, her testimony has to be treated with some caution. Schultz admits, “I was never sure of why she agreed to talk to me,” and concedes that there could have been some desire for “score settling.” The two women were very different and Boigon seems to have had no interest in Arbus’s work. Arbus, too, could have been trying to shock her straight-laced therapist. Schultz tells me he “agonized” over including what Boigon told him and his decision was influenced by the “consoling” fact that something approaching incest was, in fact, first broached by Howard Nemerov himself. In his autobiographical book, Journal of the Fictive Life published in 1965, he mentions “a little, a very little sexual experimentation with my sister.”

With her androgynous look and her slight frame, roughing it in Greenwich Village, one of Arbus’s own causes of shame as a young woman was the privilege into which she was born. Her scruffy waif look was as far as possible from the sophisticated luxury of her childhood. Her family owned Russeks, the 5th avenue department store, where her father David Nemerov worked as the marketing director. Both Patricia Bosworth and Schultz conjecture that his three children perhaps picked up on the difficulties in their parents’ marriage. Their mother was a chain-smoking socialite in the rich, beautiful, and (severely) depressed Betty Draper mold. A strained family life is the obvious Freudian interpretation for Arbus’s fascination with secrecy. “We were a family of silences,” Diane’s younger sister Renee recalled. What filled them? What was so unspeakable? The new allegation opens a whole new cache of questions.

Arbus maintained that her favorite thing was “to go where I’ve never been.” She was fascinated with doubles, with the perverse, and with the forbidden. In this light, that she should even mention incest, the most taboo secret of all, is a tantalizing insight. Could incest have been her greatest secret of all? Schultz urges caution. He says that he believes that not even Boigon was sure how literally to take Arbus’s statement about her brother.

Mild-mannered and careful, and a long way from a muck-raking biographer, Schultz again found himself in receipt of extraordinary information when he secured an interview with Phyllis and Eberhard Kronhausen, experts in human sexuality whom Arbus approached in New York in October 1968. Arbus was planning a series of photographs of couples in bed, and asked if she could shoot the Kronhausens together at home. As the Kronhausens recounted to Schultz: “Before a single shot was taken, Arbus suddenly straightened up, looked directly at the Kronhausens, and declared, ‘I can’t photograph.’ ... ‘To our complete surprise, she said: ‘I am too excited. I want to get into bed and make love with you.’”

The couple demurred by suggesting breakfast instead: “Over coffee and bagels. Arbus did what she so often did with her subjects: She told secrets. She had been shooting other couples, she said, several of them were self-described swingers, and the scenes had sometimes ended up in bed. On different occasions, Arbus revealed, she had participated in group sex.”

Arbus by this stage was separated from her husband Allan Arbus and went all out for the free love of her generation, but, as Schultz suggests, it was more a compulsion than a philosophical stance. Sex came to dominate her life and her work. “It was a way for her to feel something, when much of the time she was feeling empty,” he explains. Whilst her sexual voraciousness was detailed (to the dismay of some critics) by Patricia Bosworth, the fact that sex could be so central to the way in which she actually shot subjects is another revelation. Was the instance with the Kronhausens a one off? Had she used sex before to get what she wanted from her subjects?

In being both ordinary and extraordinary, sex and sexuality was classic Arbus territory. Far from a freakish side show, sex (the ultimate exchange of secrets, and the sharing of a secret self, as Schultz puts it) was central: so central, it emerges, in this account, that her subjects could excite her physically as well as imaginatively.

“An Emergency in Slow Motion” sounds like a dramatic description of a life that ended in disaster. In fact, it’s a powerful phrase of Arbus’s own which she used in a description of a dream in a notebook from 1959: “I am in an enormous ornate white gorgeous hotel which is on fire, doomed, but the fire is burning so slowly that people are still allowed to come and go freely…” she wrote. “It’s like the sinking Titanic… I am filled with delight but anxious and confused and cannot get to the photographing. My whole life is there. It is a sort of calm but painfully blocked ecstasy…. No one tells me what to do but I worry lest I am neglecting them or not doing something I am supposed to do. It is like an emergency in slow motion. I am in the eye of the storm.”

The nightmare was not what she saw or the danger, but that she couldn’t bear witness to what was going on. Schultz works in the genre of psychobiography but he makes plain that “to see her whole work as a result of a mental illness,” not least in the light of her eventual suicide, is a view he “detests.” It’s a refreshing approach. From Sylvia Plath to Frank O’Hara to today, someone like Amy Winehouse, there’s often a dismaying temptation to see confessional work by self-destructive artists as simply an accidental by-product of torment. In fact, this kind of reductive approach makes it easy to see why the Arbus Estate have encouraged people to judge the work solely on its own merit. Whereas Doon Arbus characterized “bits of biography” as an obfuscating “scrim of words” which could be “endangering” the work, An Emergency in Slow Motion’s sends you right back to her work, wondering once why it is so good and how she did it. The photograph we have of Arbus herself becomes a little sharper, but the spell shows no sign of abating.