Welcome to The Beast Files—epic adventures, real-life mysteries, and more stories you can’t put down. Become a Beast Inside member to keep reading.

The Nov. 22, 2013, front page of The New York Times marked the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination with a 5-by-7-inch photo of the murdered president’s flag-covered coffin being borne down the steps of the Capitol.

At the bottom right corner of the same front page was an article headlined, “After 11 Years in Prison Skakel Goes Free on Bail.”

The reference was to Michael Skakel, whose conviction had been overturned while he was serving a 20-to-life term for bludgeoning a teenage Connecticut girl to death with a golf club in 1975.

“Skakel, a cousin of the Kennedys, was ordered free from prison,” the article reported.

Michael is the nephew of Ethel Skakel Kennedy. She is the widow of Robert F. Kennedy, who can be seen in that front page photograph from 1963 standing in deepest mourning beside Jacqueline Kennedy at the bottom of the Capitol steps. RFK was himself assassinated in 1968.

Michael Skakel does not seem ever to have considered himself a Kennedy. But that had not stopped him from becoming one in the public mind. And the connection to the closest thing America has to a royal family was enough to make his release on $1.2 million bail, pending a possible retrial, big news.

The twist on this day was that it shared the front page—with a significant expanse of newsprint in between—with the JFK observance. The result can be seen as a kind of map of the Kennedy name in the American psyche.

The 50th anniversary of the assassination was a reminder of everything that had first placed the name Kennedy at such a central place in the national consciousness. The Skakel case, at the most distant edge of the mind map, is in part a tale of how an association with the Kennedy name influenced a murder investigation and trial in ways big and small, manifest and subtle.

Had the Skakels been just another wealthy family in the Belle Haven enclave of Greenwich, the investigation into the murder of 15-year-old Martha Moxley on Halloween eve of 1975 could very well have reached a quick and just resolution based on conclusive physical evidence.

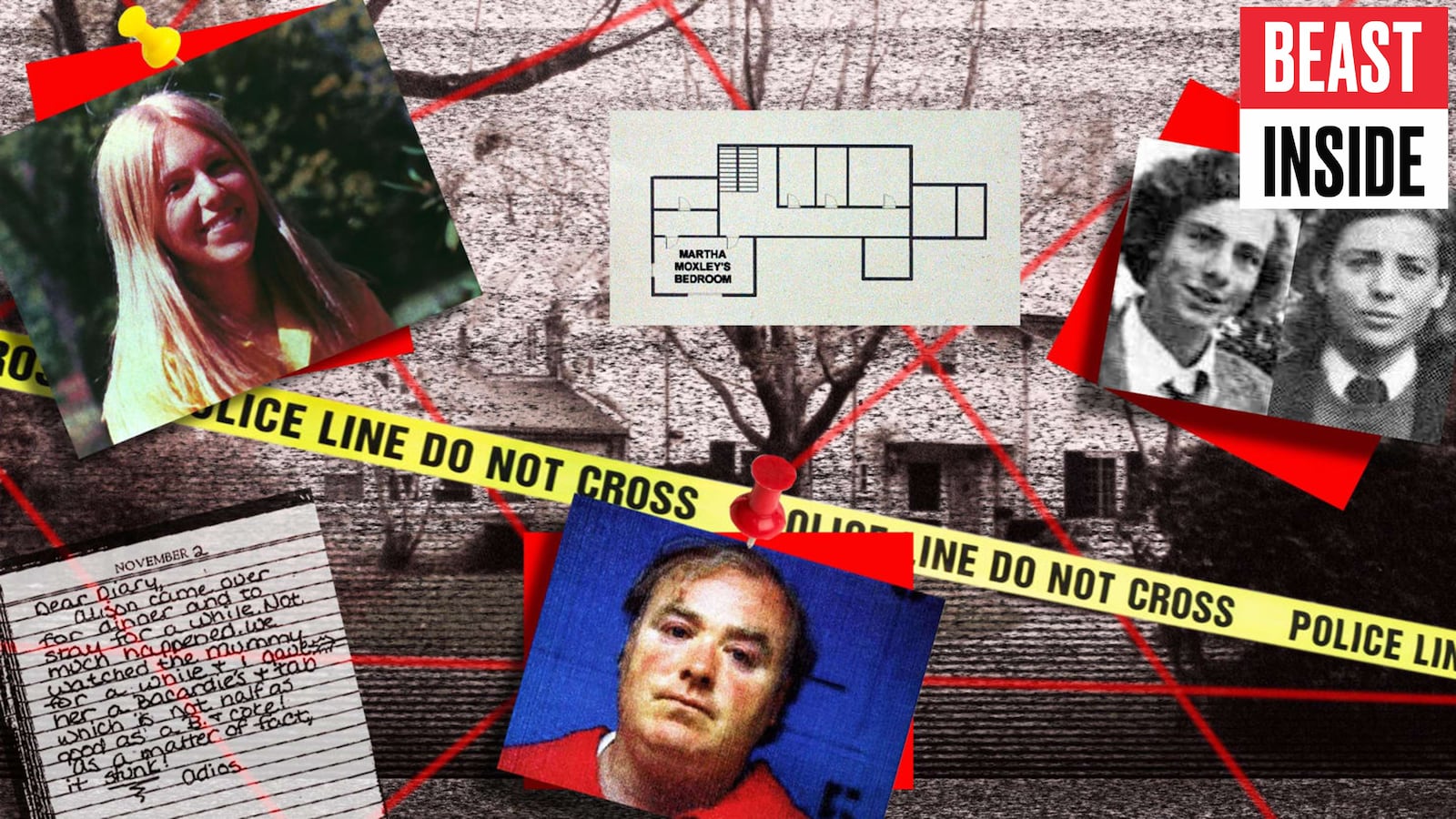

Photo of Martha Moxley when she was 14. Moxley was killed when she was 15 years old in the affluent town of Greenwich, CT, where her murder has never been solved.

Erik Freeland/GettyThe outcome might have been much the same as in another golf club murder of a teenaged girl, a case whose final disposition happened to be reported in the same 1975 issue of The New York Times as the Moxley killing. The victim in this other case was 18-year-old Michele Godbout, daughter of a New York Times outdoors columnist. She had been murdered as her bicycle was stolen in Central Park. The NYPD detectives had started with considerably less than their Connecticut counterparts had to work with in the Moxley murder, but they had soon arrested a 15-year-old from Harlem, who subsequently pleaded guilty to manslaughter.

The Times article noted that the killer in Central Park—identified only as Rodney L. because of his age—had been sentenced to just 18 months in an unlocked juvenile facility, of which six months were expected to be served. The irony is that Michael Skakel would have likely received a similar sentence had he been convicted back when he was also 15.

But there would be no arrest in Moxley’s murder for decades and the prosecutors would eventually secure a conviction only because of the incompetence of a high-profile celebrity lawyer. The verdict would be overturned, then reinstated—only to be overturned again—43 years after the killing.

The association of the Skakels with the Kennedys almost certainly made the detectives just a bit more hesitant than they otherwise might have been in pursuing the leads that were there at the very start. Even after detectives learned Moxley had last been seen alive outside the Skakel home and even after they discovered a golf club in the Skakel house that was almost certainly from the same set as the murder weapon, they failed to conduct an immediate search. They did not secure the matching club for two days, officially because the lone surviving parent in the house was not present. They then allowed the Skakels themselves to search for the rest of the golf club set with the promise to let the police know the results.

When the detectives did seek an arrest warrant seven months after the murder, it was not for Michael, but for his 17-year-old brother, Thomas Skakel. Tommy was legally an adult and had he been charged, he would have faced a term of 25 years. But the Connecticut prosecutor decreed there was insufficient evidence.

The Martha Moxley case then seemed to go nowhere. Ken Brief, the editor of two sister local newspapers, the Stamford Advocate and Greenwich Time, asked a young freelance reporter named Leonard Levitt to delve into it in 1983. Levitt worked tirelessly for months, paying particular attention to police failures in the immediate aftermath of the killing. The papers shelved the result, and the matter appeared to be on its way to being all but forgotten by everybody but the Moxley family.

Then, in 1991, another Kennedy cousin, William Kennedy Smith, was tried for rape. Smith had never even met the Skakels. That did not stop a rumor from circulating that he had been at the Skakel house the night of the Moxley murder. This triggered a flurry of tabloid interest and a suggestion that there had been a cover-up. The case was reopened and Levitt’s article finally ran eight years after it was written. The Connecticut newspapers would stay on the story and aggressively pursue it.

Over the next 11 years, those who came to have a hand in the outcome included the writer Dominick Dunne and former LAPD Detective Mark Fuhrman, as well as retired FBI agent Jim Murphy, who happened to be the agent who shot one of the hostage takers in the real-life Dog Day Afternoon bank robbery.

Both Michael and Tommy ended up offering different stories about what happened the night of the murder than they had originally told police. Michael detailed his new version in a book proposal that also promised to provide the first insider look at the dark side of “America’s royal family.”

By then, the lead Greenwich detective, Frank Garr, had decided the killer was not Tommy, but Michael. Fuhrman—having taken an interest in the case at the urging of Dunne—put forth the same opinion in his book, Murder in Greenwich. Some observers believe it was the book as much as the actual investigation that prompted the prosecutor to convene a one-judge grand jury. The judge ruled there was probable cause for an arrest, and 41-year-old Michael went on trial in 2002 for a murder that had been committed just after he turned 15.

During a preliminary hearing, a junkie named Gregory Coleman—who had been at a Maine rehab facility with a teenage Michael—took the stand. Coleman told what was almost certainly a lie about Michael boasting he would get away with the crime because he was a Kennedy.

But the statement jibed with the popular notion of Kennedy arrogance. And Michael’s million-dollar celebrity defense attorney, Mickey Sherman, failed to track down and offer up other rehab residents who could have impeached Coleman. One witness would have testified that, in truth, the only one who spoke about Michael’s connection with the Kennedys was Coleman himself, grumbling resentfully that Michael was getting special treatment. This witness would have also noted that Michael in fact seemed to be treated more harshly than others.

In at least two other, more critical instances, Sherman failed to locate and put on the stand witnesses who would have called into question major elements of the prosecution’s already tenuous case.

Perhaps most critically, Sherman failed to direct the jurors’ full attention to the suspect against whom there was the most evidence from the very start. That suspect was Tommy Skakel.

Thomas Skakel, left, and Michael Skakel

AP ImagesAs a result, the outcome of this high-visibility trial, associated with America’s most prominent family name, was determined by what the defense had on hand but failed to present.

Only because of the defense attorney’s screw-ups was the prosecution successfully able to suggest that the Skakel family had used its wealth and supposed power to engage in a cover-up. The prosecutor’s unvoiced appeal to the jury essentially was not to let Michael get away with murder because he was a Kennedy.

The case was still so weak that even some of those who were most certain of Michael’s guilt were surprised when he was actually convicted. Those who remained convinced of his innocence declared it a miscarriage of justice.

Despite Michael’s effort at one time to peddle dirt on his cousins, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. wrote a lengthy and detailed article arguing that an innocent man had been sent to prison. Robert contended there was a much stronger case against the Skakel family’s live-in tutor.

But if he seemed to be speaking out against an injustice as his father might have, Robert was acting as less a Kennedy than a Skakel cousin in his failure to acknowledge that the strongest case was in fact against Tommy. And it would be Skakel money, not Kennedy influence, that would keep the legal fight to overturn the conviction going for more than a decade.

After an appeal on various legal grounds and a petition for a new trial based on new evidence were denied, Michael’s legal campaign had one final hope: what is known as a writ of last resort in what is called the court of last resort.

In September of 2010, Michael’s new lawyers filed a writ of habeas corpus whose major contention, as set forth in 365 numbered paragraphs, was that he had been deprived of his constitutional right to effective assistance of counsel during the murder trial.

In other words, a socially prominent man of wealth and privilege who could have afforded any lawyer had one so bad that the conviction should be overturned.

A two-week hearing was held in the special habeas court in Rockville, which handles all such petitions in Connecticut. The odds were not good, as the court seldom finds in favor of the petitioner in such cases, routinely ruling against indigent defendants who had relied on a public defender.

Michael had not testified at his trial, but he did at the hearing. The courtroom hushed as he took the stand. He was now 52, heavyset and balding, the ghost of his own youth. He dismissed as “laughable” his supposed comment decades before that he could get away with murder because he was a Kennedy.

“The Kennedys and the Skakels are much like the Hatfields and McCoys,” Michael told the court. “We have a feud going way, way back.”

But however contentious the relationship might have been, it was relationship enough to continue filling courtrooms with the press and gawkers. And it was big news when Judge Thomas Bishop issued a 136-page decision throwing out the guilty verdict. Bishop took particular issue with Sherman’s decision not to present Tommy Skakel as the more likely killer.

“Attorney Sherman’s failure to point an accusatory finger at T. Skakel was and is inexplicable,” the judge wrote.

Robert. F. Kennedy Jr. hailed the decision in a TV interview, though he resisted any suggestion that the killer was in fact his other cousin, Tommy. Robert had most recently been saying the most likely suspects were two young men who had supposedly visited Belle Haven on the night of the murder with a cousin of basketball player Kobe Bryant—and who were said to have announced their intention to “go caveman on the young woman.” Robert shrugged off the judge’s view that the caveman tale was unreliable and contradicted by fact.

One of the two young men was African-American. Robert now insisted on CNN that Martha Moxley’s body had been “covered” with hair that came from an African American. Investigators had in fact found a single hair of that description on a sheet that was used to wrap Martha’s body. It was thought to have likely come from a police officer or a morgue worker.

Robert may truly believe that both Skakel cousins are innocent. And, he is no doubt anxious for an end to any talk of a Kennedy cousin having killed Martha. He may also be a little confused about the evidence.

But, the fact remained that as the nation prepared to observe the 50th anniversary of the JFK assassination, the eldest son and namesake of the murdered champion of social justice Robert F. Kennedy was essentially saying, “the black guy did it.”

The prosecution appealed the decision and found itself in the position of defending Sherman, who was at least classy enough to say little in his own defense, even through proxies, lest it hurt this client. The case would take several more twists and turns, most recently last month, more than four decades after the murder.

The effect of the Kennedy name on the case is all the more remarkable because, as Michael had said at the hearing, the Skakels and America’s most famous family had hardly felt the themselves to be a single clan at the time of the crime. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. would also note that in those years “Michael never identified himself as a ‘Kennedy cousin.’”

“On the contrary, the Kennedy and Skakel families were never close,” Robert would note. “The Skakels were Republicans who took steps against my father that my mother considered hurtful, and the families’ relationship was distant for many years.”

Robert would add, “I rarely saw the Skakel boys growing up, and would not have been able to identify Michael or his brothers in 1975.”

But there would also be this from Andy Pugh, a neighbor and Michael’s best friend at the time.

“We knew about them as Kennedys,” Pugh would be quoted saying.

In the diary that she began during the year after her family moved from Northern California to the Belle Haven enclave of Greenwich, Connecticut, Martha Moxley wrote repeatedly of the Skakels, but made no reference to any Kennedy connection. They were just boys whose backyard was across the street from her home.

She wrote in an entry dated Sept. 4, 1975, of going pool-hopping with Michael and Tommy and some friends. She went driving in Tommy’s car with Michael and four other girls the following week.

<p><u>Sept. 12, 1975</u><em>“Dear Diary, </em><em>Me, Jackie, Michael, Tom, Hope, Maureen & Andrea went driving in Tom’s car. I drove a little then & I was practically sitting on Tom’s lap ’cause I was only steering. He kept putting his hand on my knee... I drove some more & Margie & I kept yelling out the sunroof & then we went to Friendly’s & Michael treated me & he got me a double but I only wanted a single so I threw the top scoop out the window. Then I was driving again & Tom put his arm around me. He kept doing stuff like that… I think Jackie really likes Michael & I think maybe he likes her (maybe because he was drunk, but I don’t know).”</em></p>

She was with the Skakels again on Sept. 12.

<p><em>“We just goofed around on skateboards, etc. nothing special.”</em></p>

And again on Sept. 19.

<p><em>“Michael was so totally out of it that he was being a real asshole in his actions & words. He kept telling me that I was leading Tom on when I don’t like him (except as a friend). I said well how about you and Jackie? You keep telling me that you don’t like her & you’re all over her. He doesn’t understand that he can be nice to her without hanging all over her. Michael jumps to conclusions. I can’t be friends w/Tom just because I talk to him, it doesn’t mean I like him. I really have to stop going over there.” </em></p>

Another Skakel brother, John, was present.

<p><em>“Then Michael was being such an ass. They all started fighting because he was being such a big ‘he man.’ He kept calling Tom & John fags & they were ready to have a fist fight so I said, ‘Come on Jackie let’s go.’”</em></p>

Then there was this entry, where she wrote of being at a dance.

<p><u>Oct. 4, 1975</u><em>“Tom S. was being such an ass. At the dance he kept putting his arms around me and making moves.”</em></p>

Martha was back at the Skakel house on Halloween eve, known in Belle Haven as Mischief Night, when local teens traditionally pull pranks and engage in minor vandalism. The Skakel kids were in the care of a new live-in tutor, Ken Littleton. Their mother, Anne Reynolds Skakel, had died two years before, having known when she missed two critical lobs in a country club tennis tournament that the melanoma had spread to her brain. She had never recovered despite hours of prayers by her kneeling children, joined by nuns and priests with religious relics from around the world.

Skakel family with Rushton Jr. (L), Michael, Rushton Sr., and Julie.

Getty ImagesOn this night, the widowed father, Rushton Skakel, was away on a hunting trip. He had left his red Lincoln, which his children had dubbed the “lustmobile” in the belief he had customized it with a snazzy hood ornament with the apparent hope of impressing women.

Martha and two friends had come by earlier, but the Skakels had been out having dinner complete with underage cocktails at the Belle Haven Club. They were back when she returned at 9 p.m. She and her friends joined Michael in the lustmobile.

Martha was sitting next to Michael when Tommy came out of the house around 9:15 p.m., later telling detectives that he had wanted to get an audiotape from the car. He slid in on the other side of her.

At 9:30 p.m., three other Skakel brothers—Rushton Jr., Johnny, and David—came out and said they were going to drive a non-Kennedy cousin named Jimmy Terrien to his home in another part of Greenwich some 20 minutes away. They wanted to be there in time to watch a new show called Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

A page from Martha Moxley's diary.

Daily BeastBy all but one uncertain account, Michael went with them. Tommy decided to stay with Martha and her two friends. The friends would eventually tell investigators that Tommy engaged Martha in “horseplay,” and that she “forcibly and verbally rejected Tommy’s advances, pushing his hands away when he tried to touch her breasts.” The friends departed, perhaps out of embarrassment.

Tommy initially told police that he parted with Martha by the rear of the house a few minutes later and that he last saw her walking across his backyard toward her home. He would say that he then went to his room to work on a class project about Lincoln log cabins and Abraham Lincoln (“We’re studying the Puritans”) until 10:15 p.m. He said that he then went into the master bedroom to join his tutor in watching the famous chase scene of The French Connection movie, which was on television that night.

Around 10 p.m. two of the neighbors’ dogs began to bark furiously in the direction of the Moxley house. Martha’s mother, Dorothy Moxley, was painting the inside of an upstairs window when she heard what she would later describe as a commotion. She went to another window facing the direction of the noise and peered into the darkness, but saw nothing.

When Martha had not returned by early morning, Dorothy Moxley called her daughter’s friends, who said they had last seen her with Tommy Skakel. The mother telephoned the Skakel house and 19-year-old Julie Skakel, that family’s lone daughter, roused Tommy. He told Dorothy Moxley what he would initially tell the police, that he had left Martha by the back door and had gone in to do homework.

Martha was still missing until just after noon, when another teenage girl chanced to see what she at first took to be an egg-crate mattress and a sleeping bag under a large pine tree at the edge of the Moxley property. She drew closer to see that it was Martha, facedown, her head toward the Moxley house, a pair of pinwale corduroys and panties pulled below her knees.

Marks in the leaves and grass along with a 14-inch-wide blood trail told the responding police that she had been dragged some 80 feet in a zig-zag pattern, the killer apparently walking backward and looking over his shoulder to correct his course. The drag marks began at a big pool of blood where most of the assault must have taken place. A smaller splotch of blood some 50 feet away in the oval driveway indicated the attack had begun there, perhaps with a punch to the face. The absence of drag marks between those two blood spots suggested she had been conscious and had sought to escape before the killer caught up with her. She could not likely have gone from the small splotch to the larger pool if her jeans had been around her knees.

“She couldn’t have gotten 5 feet, let alone 50 feet to get over to that bloody major assault scene,” prosecutor Jonathan Benedict would argue years later.

A 1970s family photo of Martha Moxley's home.

Getty ImagesThe absence of debris inside her rolled-up panties indicated that they had been pulled at least partly down before she was dragged under the tree. There were two red marks on her inner thighs that a pathologist would describe as being consistent with someone having tried to force them apart. She had no defensive wounds or foreign DNA under her fingernails, suggesting she knew her assailant. She had been repeatedly struck on the head with such force that the golf club had broken.

The head of a Toney Penna 6 iron was found in the oval of the driveway, along with an 8-inch piece of the broken shaft. A second piece of shaft of about the same length was discovered at the start of the drag trails. The piece was smeared with blood, apparently from being forced through her neck with such force that hair by the entry wound ended up extruding from the exit wound. This piece of shaft appeared to have then been deliberately broken off a couple of inches below the grip, which was missing.

The neck wound appears to have been inflicted postmortem, a final act of savagery making some investigators believe the killer had returned following the attack. He would not likely have fled with this section of the broken club and then returned with it. He more probably had left it behind, then came back to retrieve it upon realizing it might point to him. He may have then decided to ensure that she was dead.

Detectives went to the Skakel house, where Martha had last been seen alive. They were in the mudroom when they saw something of particular note. The resulting police report reads:

“The investigators had an occasion to be in Rushton Skakel’s home… and observed the following described golf club located in a storage bin in a room located on the north side of the house, first floor.”

The club they spotted, in a barrel that also contained umbrellas and canes, was a Toney Penna 4 iron. Just below the grip was an identification band label reading:

“Mrs. R.W. Skakel, Greenwich CC, Greenwich, Conn”

A photo of evidence from the murder scene—a close-up of a golf club head.

Getty ImagesThe detectives had reason to believe that the murder weapon may have been similarly marked. And this suggested a likely reason the grip was missing.

“The person that killed Martha was aware that that name was on the club,” the then-Greenwich police chief of detectives, Thomas Keegan, later testified.

That meant the person likely resided in the Skakel house and returned immediately after the murder. Were that so, the killer would likely have left blood evidence in the residence.

The detectives nonetheless failed to conduct an immediate search. They did not even immediately secure the club they spied in the bin, officially because the one parent who resided in the house was not present.

“At this time Mr. Rushton Skakel was away on a hunting trip in Vermont and the investigators were unable to obtain permission to remove the golf club from his home,” the police report says.

The club was left in the house for two days, until after Michael and Tommy’s father had returned from his hunting trip, which was actually in upstate New York. Rushton Skakel told the detectives that the club was part of a set belonging to his late wife, Anne. He had given the clubs to his daughter, Julie.

“Interviewed Julie and she related that she last used the set of golf clubs this past summer. Julie made a quick search of the house and was unable to locate the set of clubs,” the police report states.

The report then offers one of the more remarkable lines in nearly four decades of official documents relating to the case.

“Mr. Skakel and Julie advised the investigators that they would make a thorough search of the house in an attempt to locate the golf clubs and advise the department of their findings.”

Later, some observers would suggest that the police were slow to react out of a desire to “tread lightly” when it came to residents of this exclusive gated community, who would hire off-duty cops to drive them to the airport or perform other tasks. But the detectives had reacted aggressively when they interviewed a 27-year-old Yale graduate named Edward Hammond who lived next door to the Moxleys and who was said by neighbors to be “odd.” He was found to have a blood stain on the leg of a pair of pants that he said came from a household accident. The police brought him in for questioning, taking fingerprints, fingernail scrapings, and hair samples.

And, even as they left the golf club sitting in the Skakel home, the detectives immediately and thoroughly searched the house that Hammond shared with his mother, going through closets and the washing machine and dryer, even the trash cans. They vouchered as possible evidence everything from a box of condoms to a Yale-Cornell football game ticket stub to two empty bottles of Schweppes Bitter Lemon to an empty Crest toothpaste box to two Marlboro cigarette butts. The blood on the pants would prove not to be Martha’s.

There is no telling what the detectives might have found had they immediately conducted a similar search of the Skakel home rather than just leave it to Julie and her dad two days later. The easy explanation for this lapse is that the detectives were either intimidated or accorded the Skakels special treatment or both. But the resolve with which they did subsequently act suggests that at first they simply thought of the Skakels differently. And the determining difference between the Skakels and their neighbors seems to have been that most resonant of family connections.

The detectives did arrange for Tommy to undergo a lie detector test the same day that they finally secured the golf club. The results were inconclusive. He would be deemed truthful in a subsequent test.

In an interview with the detectives, Tommy sought to explain his absence from his room when Littleton checked on him at 10 p.m. by saying he had gone to another part of the house to get a book on Abraham Lincoln for his class project. But the detectives also interviewed Tommy’s teacher at the Brunswick School and learned there had been no such assignment. That raised the question of why Tommy would have felt a need to tell such a detailed lie, or indeed to have told the same lie when Martha’s mother was looking for her—before anybody but the killer knew Martha was dead.

Tommy further admitted during questioning that he had indeed roughhoused with Martha after his brothers drove off. The police would report in an affidavit, “Thomas Skakel first denied pushing or shoving Martha Moxley before she left him, but later did state in fact that he was pushing and jostling with Martha Moxley but could not remember exactly what went on.”

The affidavit was presented to prosecutors when detectives sought an arrest warrant seven months after the murder.

The document further states, “A check of the medical and psychological records of Thomas Skakel revealed that he suffered a skull fracture at age four, and as a result suffered from frequent and quite sudden outbursts of severe physical violence, incontinence and threats against siblings.

“On numerous occasions, Thomas Skakel has displayed acts of violence and rage and on one occasion he slashed an oil painting of himself across the groin area,” the affidavit notes.

The file included a summary of an interview with a friend of Martha’s named Allison Moore. She told detectives that she had spoken to Martha earlier on the week of the murder.

“Allison went on to say that the victim… told her that Tom Skakel wanted to date her, but that she had said ‘No,’” the report read. “She also related that the victim told her that Tom was very aggressive, going on to say that the victim also said that she thought that Tom was strange.”

Another report recounted an interview with Franz Josef Wittine, the Skakel’s handyman and gardener, who “had observed on several occasions T. Skakel leave the house for the purpose of walking, carrying a golf club from the house.”

But while the detectives reported finding a second Toney Penna club at the Skakel residence—a 5 iron—they had conducted the search long after they might have discovered the missing grip of the murder weapon or other physical evidence. The prosecutor, Fairfield County State’s Attorney Donald Browne, said there was not enough to charge Tommy and declined to convene a grand jury.

“We have a circumstantial evidence case, with no witnesses,” Browne told reporters. “Unfortunately, we have circumstances that point in several different directions.”

The case turned as cold as a case can be for the next 15 years.

We know you’re hooked. Read the next installment… in which the Skakel brothers change their stories about where they were, and what they were doing, on the night of Martha’s murder.