The underwater world was almost entirely unknown to the public in the nineteenth century. Once filmmakers developed the technology to film below the ocean’s surface, starting with Williamson’s photosphere pioneered in 1914, they discovered immense potential but also a challenge. While filmmakers could shape underwater imagery according to their visions, at the same time, they had to work to convince audiences that it was indeed the undersea environment, a challenge all the greater because the environment was inaccessible to general publics during the first decades of underwater filming. Leisure diving would not develop until the advent of scuba in the post–World War II era.

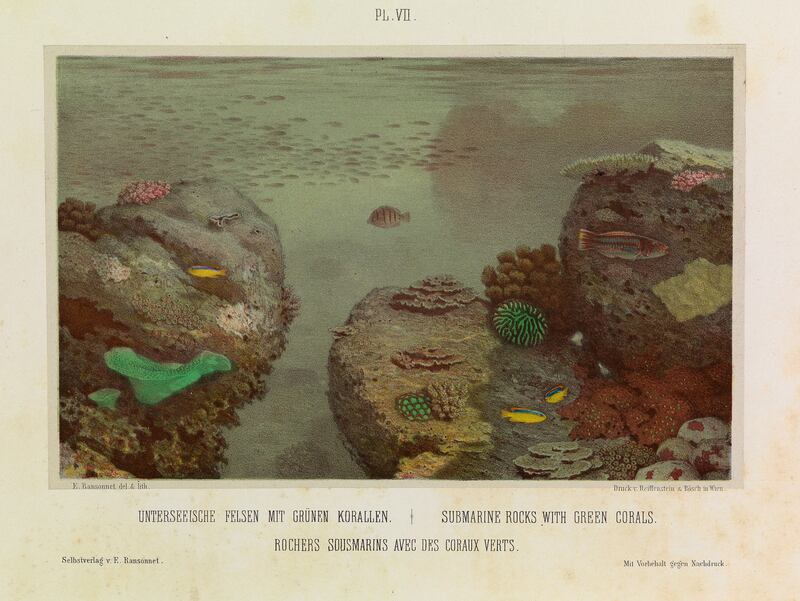

Amidst the public’s pervasive hydrophobia across the nineteenth century, there were intrepid adventurers who explored the world below the ocean’s surface. Baron Eugen von Ransonnet-Villez, an Austrian naturalist, became captivated by the beauty of tropical corals in the 1860s. Ransonnet published two travel books with the first extended descriptions, and also the first visual images, based on prolonged, firsthand observation in the Western tradition.

For Travels from Cairo to Tor to the Coral Reefs (Reise von Kairo nach Tor zu den Korallenbänken) (1863), Ransonnet was free diving. Even with his limited time below, he noted submarine luminosity and the behavior of color: “How peculiar things appear under water! Though one cannot exactly distinguish the contours in the deep, yet everything gleams in beautiful and strange illumination! Brown, violet, orange, in yellow and blue light, everything glows towards the diver.”

In the years after publishing this account, Ransonnet designed a custom diving bell with a window so that he could sketch below. He used this diving bell for his trip to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and included both verbal descriptions and engravings in Sketches of the Inhabitants, Animal Life and Vegetation in the Lowlands and High Mountains of Ceylon (1867). There, for example, Ransonnet observed again the details of altered visual perception below. “Strange seemed the light effects down there in the sea so I paid special attention to it. Bluegreen is the basic tint of the underwater landscape and especially of all bright objects, whereas dark, e.g. blackish rocks and corals, and far away shadows, seem to be wrapped in a monotone maroon, which is in complementary relation to the colour of the water.” Despite such novel observations, these works “remarkably . . . did not command much attention at the time.”

From the scant information in secondary literature, it seems that both scientific and public interest in submarine reality started to crystallize in the 1880s–1890s. Within this time frame, historian of scientific diving and underwater photography Hermann Heberlein names several noteworthy scientists who turned their attention to underwater optics. The most famous was biologist and artist Ernst Haeckel, who knew of Ransonnet’s depictions. In Nature, Haeckel published an article where he lamented his lack of access to such a diving bell. Nonetheless, he commented that by training his eyes to remain open, he could observe “the mystic green light in which the submarine world was bathed, so different from the rosy light of the upper air. The forms and movements of the swarms of animals peopling the coral banks were doubly curious and interesting thus seen.

Marine biologist Hermann Fol, a student of Haeckel’s, realized that such conditions were worth attention in their own right. In an article from 1890, based on his experience diving in the Mediterranean, Fol described underwater optics and tied them to two practical purposes—submarine navigation and underwater photography. While the shallow depth of field thwarted sight for navigating undersea vessels, Fol was optimistic about underwater photography. He noted the loss of red light and surmised that the blue rays that last the longest are, in Fol’s estimation, “the rays that act with the greatest energy on the photographic plate.” Fol also noted the altered submarine color spectrum, the effect on visibility of different angles of the sun, and varying turbidity of water in different zones. (His comments about poor underwater visibility also raised for him the question about whether fish were nearsighted: “what use would distance vision be, because in any case, they would only be able to see several meters?”)

In 1890, when Fol published his observations, experimentation for developing reliable processes for underwater photography was under way. French marine biologist Louis Boutan is credited by photographic historians with the first clear, reliable underwater photography. In 1900, Boutan outlined his method thoroughly in the book La photographie sous-marine et les progrès de la photographie. Boutan’s precursors included William Thompson, who took an exposure in Weymouth Bay in February 1856, as well as German submarine inventor Wilhelm Bauer, and the previously mentioned Frenchman Bazin who upgraded the diving chamber.

Slides of Boutan’s photos were shown at the great Paris World’s Fair of 1900. By this time, curiosity, if not knowledge, about submarine conditions was growing in the general public. People were fascinated by the real-life success of Alexander Lambert, “who had recovered the vast majority of gold bullion from the 1885 wreck of the Alphonso XII in the Canaries.” A particularly successful melodrama on the London stage in 1897 was Cecil Raleigh and Henry Hamilton’s The White Heather, culminating in an underwater fight scene represented in advertisements for the production, which was popular enough to cross the Atlantic to Broadway. H. G. Wells noted the change in color of the sea in portraying the dive of a submersible into the abyssal depths inhabited by aliens in his short story “In the Abyss” (1896), which was one inspiration for James Cameron’s The Abyss (1989). As the protagonist, Elstead, plunges downward, he “saw the water all around him greeny-blue, with an attenuate light filtering down from above, and a shoal of little floating things went rushing up past him. . . . [I]t grew darker and darker, until the water above was as dark as the midnight sky.” Further, “little transparent things in the water developed a faint glint of luminosity,” as they “shot past him,” suggesting bioluminescence.

If this time frame correctly identifies the intensifying public curiosity about submarine reality, it coincides with the invention of underwater photography. Did general interest in the environment lead inventors to take photography below? Did public curiosity grow as submarine photography revealed the unique qualities of submarine life? Or, as is often the case, were public attention and new technological advancements mutually enhancing?

Excerpted from THE UNDERWATER EYE: How the Movie Camera Opened the Depths and Unleashed New Realms of Fantasy by Margaret Cohen. Copyright © 2022 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.