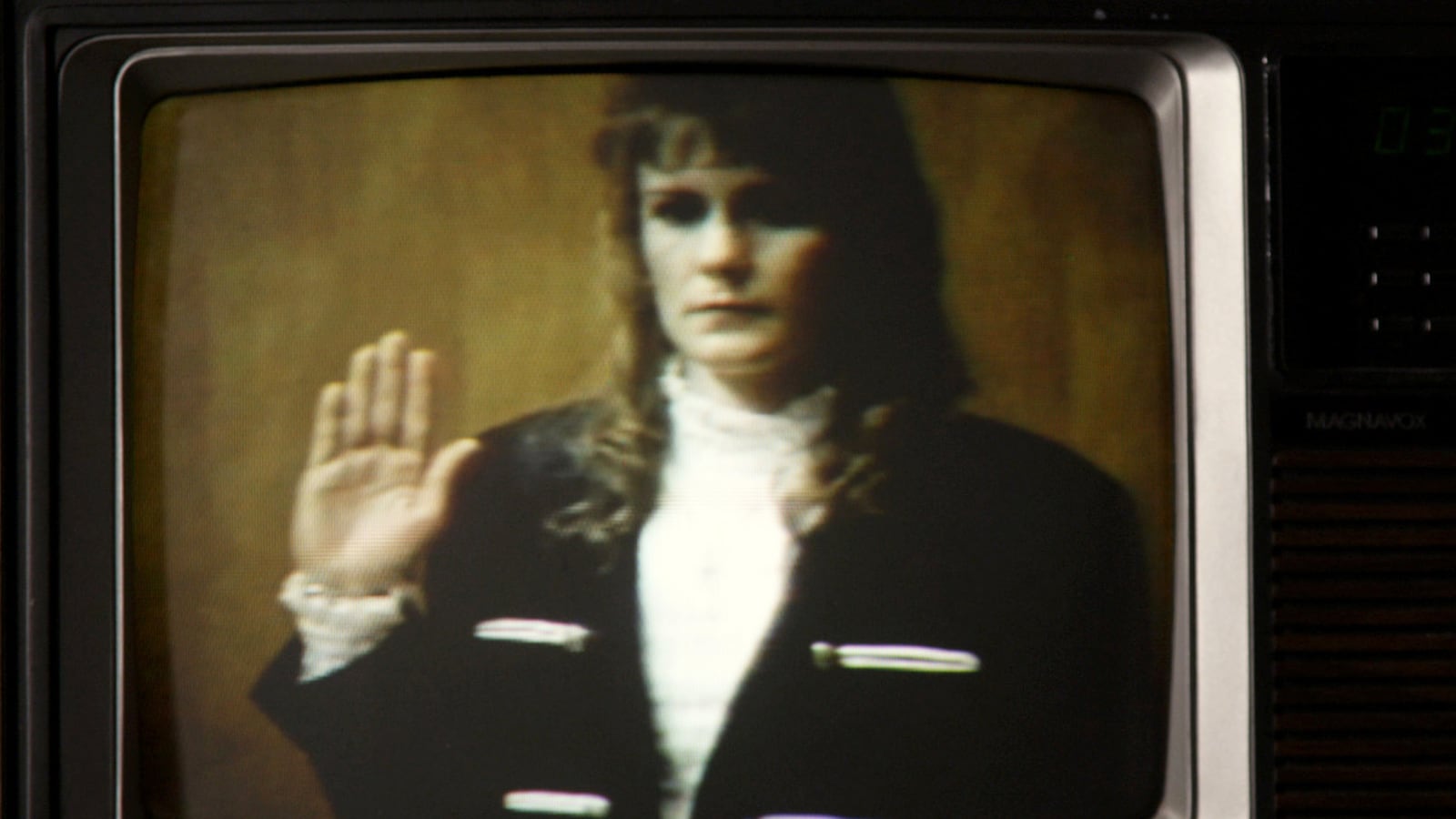

Sex. Seduction. Edgy teens. Murder. And at the center of it all: a striking blond cheerleader-cum-schoolteacher. Yes, the curious case of Pamela Smart had it all. It was also the first murder trial ever covered live on television and as such, became a bona fide cultural phenomenon. Groups of men and women held viewing parties. The trial had higher ratings than most afternoon soap operas. It was litigation as entertainment—a farcical tangle of events that titillated a ready, willing, and able country.

On May 1, 1990, Pamela Smart came home to find her condominium in Derry, New Hampshire, turned upside down and her 24-year-old husband, Greggory, lying on the ground with a bullet hole in his head. It looked like Greg was trying to stop a burglary, and was killed in the ensuing confrontation. Then things took a strange turn. Three rough-hewn high school teenagers from the neighboring town of Seabrook—15-year-olds Billy Flynn, Pete Randall, and J.R. Lattime—were arrested for the murder. Things got even stranger when Smart was arrested for allegedly seducing Flynn and convincing the boy and his friends to kill the man she had been married to for less than a year.

If this whole wacky scenario sounds familiar, it should. The story served as the basis for Joyce Maynard’s novel To Die For, which was subsequently adapted into the Gus Van Sant film of the same name starring Nicole Kidman as a sociopathic, fame-obsessed sexpot who manipulates a couple of teens (Joaquin Phoenix, Casey Affleck) into murdering her schlubby husband, played by Matt Dillon.

Despite maintaining her innocence, Smart was eventually sentenced to life in prison without parole, and is currently serving her time at the maximum-security Bedford Hills Correction Facility for Women in Westchester, New York. Filmmaker Jeremiah Zagar’s new documentary Captivated: The Trials of Pamela Smart, which made its world premiere at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival and will air on HBO later this year, pokes several holes in the prosecution’s case against Pamela Smart, and argues—quite convincingly—that, thanks to the media circus that ensued, she wasn’t given a fair shake.

Smart, an aspiring TV news reporter, was working as a media coordinator at Winnacunnet High School in Hampton, New Hampshire. She met Flynn while volunteering at a local drug awareness program, and also befriended his friend, Cecelia Pierce, who would later serve as her intern. From here, the details are murky. Both Smart and Flynn admitted to engaging in a sexual relationship. Smart claims that, after eight weeks, she felt guilty and broke off the relationship, leading an angry Flynn to murder her husband out of jealousy. Flynn alleges that Smart threatened to stop having sex with him if he didn’t off her husband. After the three boys were arrested, police received an anonymous tip that Pierce knew of Smart’s alleged murder plot, and agreed to wear a wire to try and catch her teacher saying some incriminating things on tape (which she did). Smart was subsequently arrested on Aug. 1, 1990, and the trial began on March 4, 1991.

Within those seven months, the media went absolutely insane, portraying Smart as an “ice princess” and “black widow” seductress who manipulated the boys into doing her dirty work. According to a contract obtained by the filmmakers, on Sept. 14, 1990, Pierce sold the rights to her story to a production company called Once Upon A Time Films for $100,000. Meanwhile Bill Spencer, a former local WMUR reporter, made the rounds on The Phil Donahue Show, Geraldo, Hard Copy, you name it, repeatedly claiming that all the “evidence” pointed against Smart. Spencer and his station even produced a TV documentary about the Smart case called Anatomy of a Murder, which was broadcast two days before jurors were selected. He comes across like Richard Thornburg, the asshole, media-whore reporter from Die Hard.

On the first day of the trial, prosecutor Diane Nicolosi said, “That was the first time the defendant had sexual intercourse with Bill. He was a virgin, a boy in way over his head with this relationship.” From there, the die was cast. Smart was the Lady Macbeth-like spouse hell-bent on murder, while Flynn was the naïve young boy who’d fallen prey to her bloodlust.

“I was under the belief that the only people that went to prison were people that were guilty, and if you were innocent, it would be proven in a court of law,” Smart says in one of several interviews with the filmmakers.

And the jury was, it seems, subject to an outrageous amount of pre-trial prejudice. For whatever reason, Judge Gray ruled against having the jury be sequestered, so they were likely very privy to the media frenzy surrounding the case.

“There was media everywhere,” Juror #13, who recorded her thoughts daily via tape recorder during the trial, would later reveal. “I felt like a bug in a glass jar.”

The court was presented with suggestive photos that Smart had allegedly shared with Flynn of her in a bra and panties—perfectly fitting the prosecution’s narrative—but, according to Smart’s academic advisor in prison, Flynn had “never seen them” and the photos were a result of “she and her friend Tracy posing for each other to enter into a contest.”

Later, Flynn takes the stand. He claims that, while Randall held him down on his knees, he executed Smart’s husband with a gunshot to the back of the head. “I didn’t want to kill Greg,” he says, wiping away tears. “I wanted to be with Pam, and that’s what I had to do to be with Pam, but I didn’t want to kill Greg.” He pauses. “I said, god forgive me… I pulled the trigger.”

“I would say they’re crocodile tears,” Juror #13 observed on her audio diary. The three boys agreed to plea bargains so that they’d testify against Smart, with Flynn pleading down to a second-degree murder charge. After the boys testified, they were seen exiting the courthouse smiling, chewing gum, and slapping their hands together.

“They were doing lines before they were going to testify,” Ricky Davis, a former inmate at Rockingham County Jail with Flynn and co., claims in the film. “And [Flynn] goes, ‘It makes me more emotional on the stand.” Davis backs up other reports that claimed Flynn was bragging in prison about his “performance” on the stand, but Judge Gray denied the defense’s attempt at recalling Flynn. Even Gray, it seems, got caught up in the wonder of it all. At one point, he reportedly uttered that he wished Clint Eastwood would play him in the movie adaptation.

Other holes in the prosecution’s case include the initial testimony of Raymond Fowler, a passenger in the boys’ getaway car the night of the murder who, when asked if Pamela asked Bill to kill her husband, replied, “I don’t know. I didn’t talk to her.” “Why didn’t you go to the police when you knew that a guy had been murdered?” the detective asked. “Probably ‘cause they’d try to kill me,” replied Fowler. Fowler’s brother also says that the three teens were housed in the same cell block, while Fowler was in a different cell block, which gave the three plenty of time to “get their stories straight” before the trial. Why the boys were allowed to be housed in the same cell block together is anyone’s guess.

Then there’s the matter of Pierce’s damning audio. It was such poor quality that even Spencer admits you could only hear “every fifth world” and that it was all “garbled.” The prosecution had to hire an enhancer to improve the sound quality of the Smart wire tape, and came up with this statement: “If you tell the fuckin’ truth, you’re probably going to be arrested,” Smart is heard saying. “And even if you’re not arrested… you’re going to have to go and you’re going to have to send Bill, Pete, J.R., and me to the fuckin’ slammer for the rest of our entire life.” Unfortunately, no one could make out what was said before and after that statement on the tape, so it could, perhaps, have been taken out of context.

“On the one piece of evidence that would get her, somewhere lies the truth and we’re never going to really know what it is,” Juror #13 said.

On March 22, 1991, Smart was found guilty of “being an accomplice to first-degree murder, conspiracy to commit murder, and witness tampering,” and was sentenced to life in prison without parole. Smart argued that she was given an unfair trial thanks to the constant media coverage, but her appeals fell on deaf ears.

Her life became a living hell after that. On Sept. 24, 1991, the TV movie Murder in New Hampshire: The Pamela Wojas Smart Story aired on CBS, with Helen Hunt starring as Smart. In 1993, she was woken up at 4 a.m. one morning and transferred from New Hampshire to the prison in New York where she currently resides. “I thought they were going to kill me,” she says. For the first time ever in the State of New Hampshire, an interstate compact with the State of New York was instituted allowing for the transfer of prisoners. Then, in 1995, To Die For was released.

“This is not my movie… nothing in here is my story,” Smart says of To Die For. “These are the types of things that prevent me from getting back into court [to appeal].”

In 1996, Smart was severely beaten in prison by two inmates, who broke her eye socket and left her with a metal plate in her head. She was put on Prozac after the beatings, and contemplated suicide. Later, in 2003, pictures of a half-naked Smart—taken in prison—were published in The National Enquirer. Smart claims that she was raped by a prison guard, who forced her to pose for the photos, which he then sold to the tabloid rag. Despite the hardships, Smart managed to earn two masters degrees in prison—one in criminal law and one in English literature—and her friends in the film claim she was “a geek” who graduated from Florida State University in just over three years with a 3.85 GPA, a far cry from her “sexpot” image.

Even though it may not have been proven “beyond a reasonable doubt” that Smart ordered the murder of her husband, she’s serving life in prison without the prospect of parole, while Fowler was paroled in 2003, Lattime was paroled in 2005, and both Flynn and Randall, the boys who actually committed the murder, are eligible for parole in 2015.

Towards the end of Captivated, Fowler sat down with the filmmakers for an interview. They think it could “blow the case wide open,” since Fowler’s initial testimony with detectives pointed to Smart’s innocence. Instead, he recounts an episode reaffirming Smart’s guilt that is, oddly enough, lifted almost verbatim from the Helen Hunt-Smart movie.

“What a great movie it’ll be if I get out, right?” says Smart in the film’s final scene. “You’d just have the greatest footage in America—me coming out of the door, leaving the prison, and… Oh god."

Sometimes truth is stranger than fiction.