On Jan. 1 this coming year, Americans, black and white, will be celebrating a historic triumph. On that day, 150 years ago, President Abraham Lincoln ordered the abolition of slavery throughout the United States. But historians are already preemptively dousing our enthusiasm for the Emancipation Proclamation. Many have pointed out that, in reality, the order didn’t actually free many slaves—a mere 50,000 immediately; the rest of the 4 million slaves lived in Southern states that Lincoln had no control over. Others have noted that the death toll of the Civil War itself might give us pause in celebrating 750,000 Americans killed, the bloodiest war in U.S. history. The merit of it ending slavery is unquestionable. But was there not a more peaceful alternative?

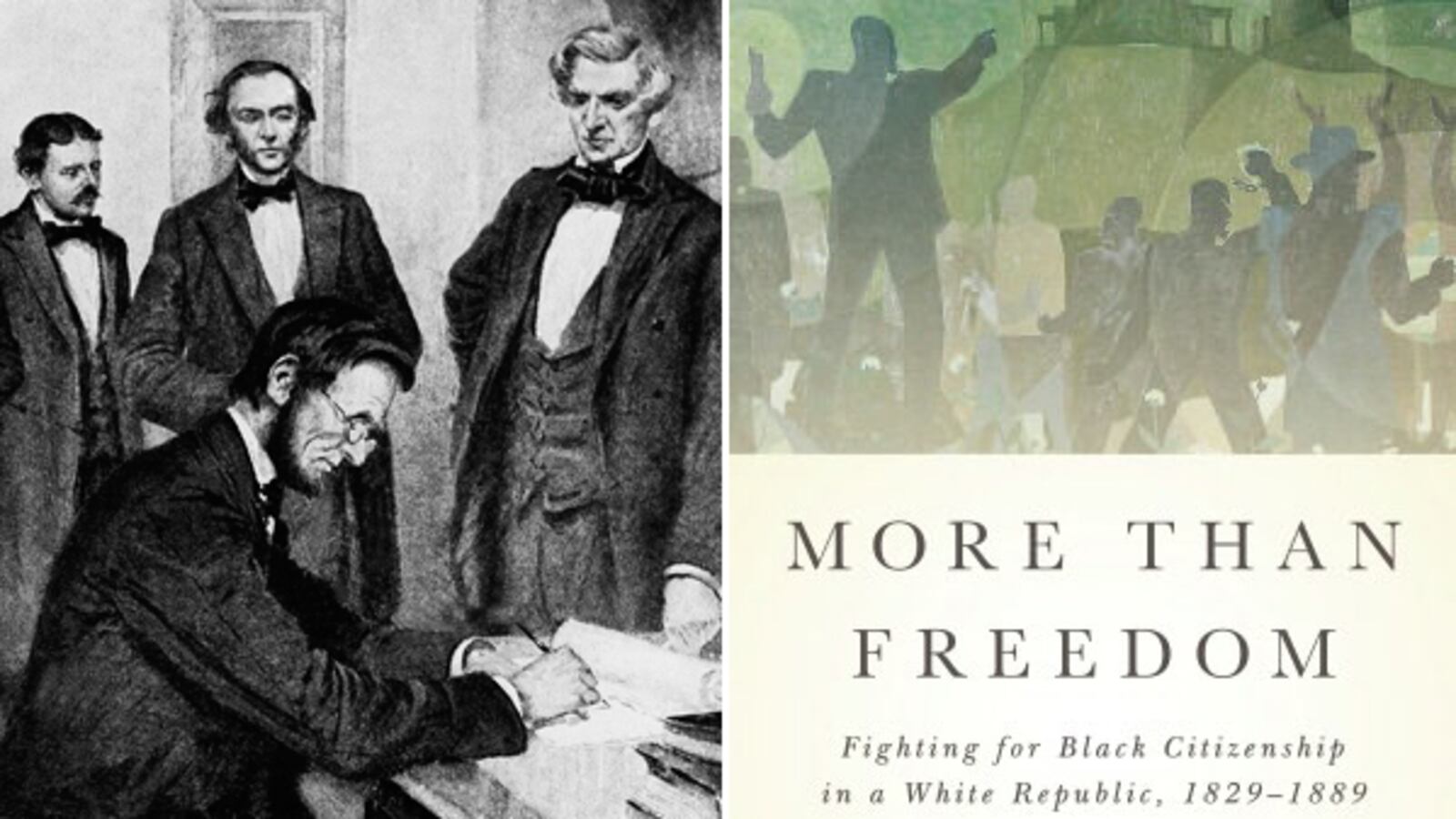

The best argument against any sort of party may be More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889, by the University of Wisconsin historian Stephen Kantrowitz. He takes the long view, in that the emancipation was, at best, a highly-qualified success, because the leaders of the abolitionist movement—a small group of larger forgotten black activists based in Boston—had viewed the end of slavery as just one step in a much larger fight for full equality.

Many readers will be familiar with the postwar reemergence of racism in the guise of Southern Jim Crow laws and the Ku Klux Klan. But it’s doubtful that they will have known that, as early as the 1820s, blacks were already fighting for full equality. They wanted the right to vote, run for office, serve in the military, attend white schools—all of which reached its zenith with Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil-rights movement, a century and a half later.

Who knew, for instance, that Jim Crow, the term for de jure segregation, actually began in the 1820s in Massachusetts, where the state’s free black population was legally barred from riding in the same train cars as whites? You’ve heard of Frederick Douglass; but how about black leaders like Lewis Hayden and William Nell, who were fighting to desegregate those trains, the state’s militia, and Boston’s public schools years before Douglass entered the scene?

To be sure, many of the better-known figures get lengthy treatment in More Than Freedom: Douglass, the fugitive slave rescuer Harriet Tubman, the white abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison. But Kantrowitz is at pains to show how rife with division the abolitionist camp was, and that, in fact, “abolition” is a misnomer entirely. The word implies that ending slavery was the activists’ only mission, when in fact many of its leaders saw it only as the first step to a fuller notion of citizenship. Abolition, he argues, “was too small a box to contain their aspirations.”

Kantrowitz may be at fault for focusing almost exclusively on a small group of black Bostonians. No matter how influential they were, they could not be said to speak for a people whose vast majority—nearly 90 percent—lived in the South at the time of the Civil War. But those black Bostonians were clearly an important lot. The first was David Walker, whose explosive 1829 pamphlet, “An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World,” noted that blacks in America deserved not only to be free but something more: fully equal “citizens.” Even white abolitionists were taken aback by Walker’s “temerity,” though, of course, the logic is obvious, not bold. Kantrowitz argues that Walker sparked a movement that more radical (and famous) white abolitionists like Garrison are incorrectly credited with.

Kantrowitz’s elegant, nuanced detailing of how blacks activists began and outlasted the limited “abolitionist” movement is not angry or one-sided. He’s an even-handed historian, quick to show the internal divisions within the black activists’ camp as well. When, for instance, some black activists attempted to desegregate Boston’s public schools in the 1840s, others fought passionately against them. Detractors argued that it would be better for blacks to have their own schools, given the discrimination they might face in white-dominated ones. The pro-integrationist William Nell countered that such reasoning would refute a critical strategy of black activists: to fight inequality by changing the hearts and minds of white Americans. Not until whites and blacks were exposed to each other’s social worlds, where they learned, prayed, drank, slept, and ate together, would the legal battle over policy be more easily won.

The idea that equality was not only a legal term but a more expansive one encompassing all aspects of life is central to Kantrowitz. Otherwise, it could be argued that black activists had in large part succeeded by the 1870s. Slavery was not only abolished, but also two more constitutional amendments, the 14th and 15th, had explicitly guaranteed blacks equal protection under the law, as well as the right to vote. It would be easy to say that winning the Civil War and the passage of the post-war amendments effectively ended the black activists’ work. Many in fact had: Garrison, for instance, wanted to close up shop in 1865 and put an end to his crusading American Anti-Slavery Society and its paper, The Liberator. When former black allies attacked him for this, he retorted glibly that the “other work” of equal citizenship was “incidental” to his society’s mission.

That would only foreshadow the “fractured antislavery world” to come, as Kantrowitz calls it, which emerged after the Civil War. Women suffragists had been staunch allies of black activists before the war, and vice versa. But all that changed after the war, a fact poignantly shown by a heated exchange between Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass. When women suffragists attacked black leaders for abandoning them in their fight for voting rights, Douglass was no less flip than Garrison: “When women, because they are women, are hunted down through the cities of New York and New Orleans … then they will have an urgency to obtain a ballot equal to our own.” To which Anthony replied: “But we say, if you will not give the whole loaf of suffrage to the entire people, give it to the most intelligent first.”

And on it went. Black activists were eventually abandoned by former allies, divided amongst themselves, and died off. But, worst of all, they were not remembered. It is Kantrowitz’s great achievement that they are forgotten no more.